Elly Sougioultzoglou-Seraidari (1899-1998), better known as Nelly’s, was the first artist to photograph a nude dancer on the Acropolis, juxtaposing majestic motion with the eternal stillness of Greece’s legendary monuments. The pioneering photographer’s singular, daring vision was ahead of its time, and probably remains a profound, if not largely unconscious inspiration to the artists of today. She was also the first photographer in Greece to publish a color photograph, and created the Greek Tourism Organization’s first ever promotional poster.

Although she was recognized, celebrated, and entrusted with important projects throughout her career, she is only finally now receiving the appropriate acknowledgment and respect for her work through this fascinating retrospective at the Benaki Museum’s Pireos Street annex, which will run until July 23.

Born in Asia Minor in 1899, Elly Sougioultzoglou-Seraidari traveled to Dresden, Germany to study photography under the tutorage of Hugo Erfurth and later his student Franz Fiedler, learning practices and outlooks that were unknown to Greek society at the time.

© Benaki Museum/Photographic Archives

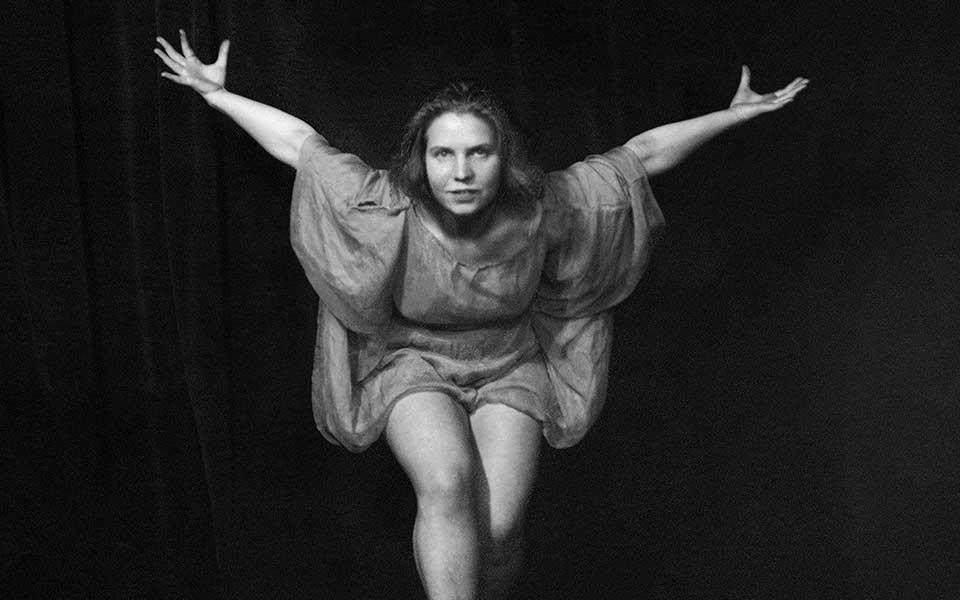

Only three years after moving to Athens and opening her studio on Ermou Street in 1924, Nelly’s photographed the prima ballerina of the Opera Comique Mona Paiva on the Acropolis. During the shoot, Nelly relates that she was so enchanted by the beauty of the dancer’s body in the Greek light that she asked Paiva if she could photograph her in the nude, and the dancer consented. Once published, the images were condemned by the Greek press, which described them as “provocative profanity on the sacred monument.” In response to this backlash, writer Pavlos Nirvanas published an open letter in the “Elefthero Vima” newspaper reminding the public that to ancient Greeks, the naked body represented the supreme expression of truth and was the embodiment of the classical ideal.

This key moment in Nelly’s career established that what she created was art and that it was not only acceptable but vital. Five years after photographing Paiva she captured Russian dancer Elizaveta Nikolska at the Parthenon, in images so dynamic and magnificent that they continue to astound viewers today.

Nelly’s creative and aesthetic impact on the public began almost immediately upon her arrival to Greece in 1924, and as anyone visiting the exhibition will see, she never stopped experimenting with advanced ideas and scenarios.

In 1984, Nelly’s donated her life’s work, in the form of 50,000 negatives and 20,000 prints to the Benaki Museum, together with archival materials, film reels, and personal belongings such as her cameras, darkroom equipment, and even beautiful porcelain items that she painted and sold in New York. From 1984 to 1998, the Benaki Museum’s Photographic Archives department (which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year) dedicated itself to sorting through the materials and putting them into their correct order, with Nelly’s assistance.

© Benaki Museum/Photographic Archives

In the exhibition, Nelly’s diverse body of work has been organized into three chapters, each corresponding to one of the three cities that influenced her photographic perspective.

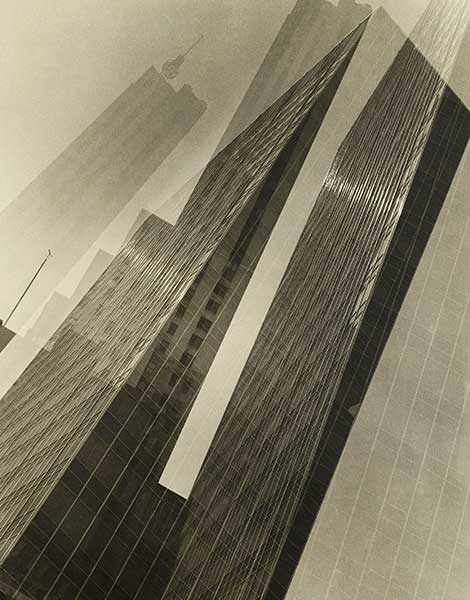

The first chapter covers her student years in Dresden during the early 1920s. The second chapter explores her time in Athens, where she played a dynamic role within the city’s photographic community. Finally, the third chapter covers her years in New York, where she moved to in 1939 and spent 27 years working before retiring in 1966.

There are many sub-sections such as “Old Athens,” in which one can see pictures Nelly took around the city in the mid-1920s, showing long-lost aspects of neighborhoods like Acropolis and Plaka; “Refugee Sorrows,” photos from Attica’s refugee camps, that Nelly presented in an exhibition on behalf of the American Near East Relief in 1925; images from the Greek countryside, shot during her tour of the Peloponnese, Central Greece, the Cycladic Islands, and Crete; the “Delphic Festivals,” presenting photos from her collaboration with Eva Palmer-Sikelianou and her thespian group in 1927 and from the Second Delphic Festival of 1930; “Greek Fashion,” which showcases Nelly’s photos from the late 1930s of models posing in front of ancient Greek or Byzantine monuments, as well as many sections from her years in New York, during which she took photographs of fashion models, Greek weddings and baptisms, American personalities and even for advertising campaigns.

© Benaki Museum/Photographic Archives

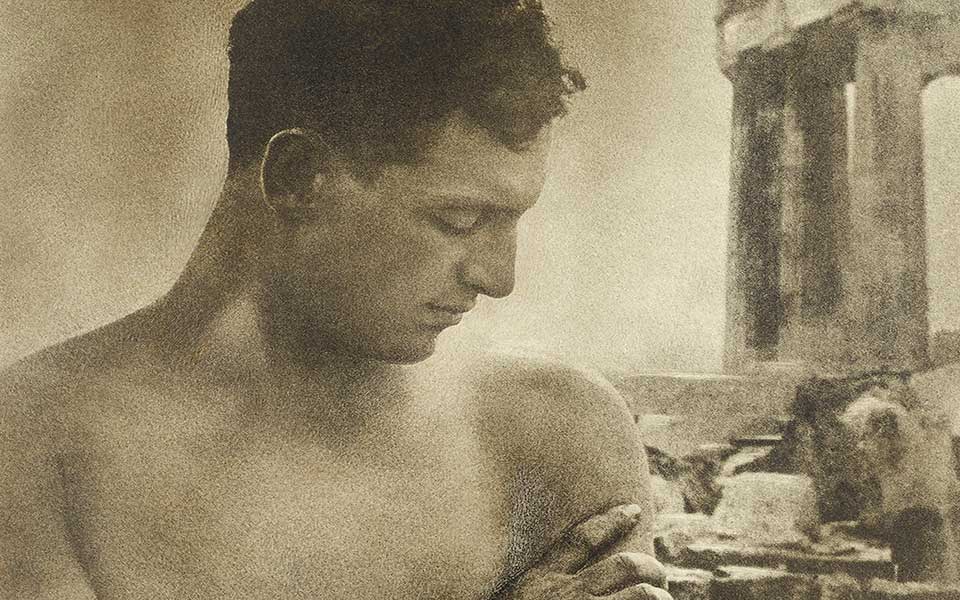

Nelly’s artistic achievements are noteworthy, particularly her exceptional experimentation with natural light and photography of ancient temples. Her work poignantly showcases the interrelationship between the two. Meanwhile, her photography also stood out for reflecting an “idealized” vision of Greece, something that the Greek state recognized. Indeed, a core part of Nelly’s work in the late 1950s to mid-1960s was born from her collaboration with Greece’s Ministry of Press and Tourism, for which she produced the first-ever tourism poster of Greece. She also collaborated on ventures presenting Greece’s antiquities, the countryside, and its communities as well as state-run industries (from farms to factories to educational institutions). Her pictures were presented in the Greek tourism magazine “En Grece,” which was published in three languages.

Aliki Tsirgialou, Head of the Benaki Museum Photographic Archives, who worked with her team on putting the exhibition together for over seven years, spoke about the importance of putting the photos into the correct sequence while at the same time presenting the multifaceted actions of the photographer throughout her career. “What we want to show in this exhibition is how broad the spectrum of her work was because often her name is automatically associated with the famous image of Nikolska dancing at the Parthenon, so our desire was to show how much more she created beyond that. Nelly was always eager to learn the newest techniques, advance her abilities and experiment with novel methods and subjects, and we have presented her legacy and its effect here.”

© Benaki Museum/Photographic Archives

© Benaki Museum/Photographic Archives

Apart from being full of fascinating portraits, scenes, and many historical elements that have by now been swept away by the tides of time, the exhibition succeeds in gently drawing the visitor into Nelly’s world. With soothing lighting, an immersive audiovisual projection on a curved wall created by Babis Alexiadis, who breathed life into images of Nikolska dancing at the Parthenon, artifacts like posters, postcards, costumes (from the Delphic Games), a staging of Nelly’s dark room in New York, music and finally, in the last room of the exhibition, the screening of a short film presenting Nelly’s talking about her career, you will leave the museum feeling replete with a new awareness of art, history, culture, creative vision, human nature and the timelessness of beauty.