“Every Choice a Chef Makes on a Menu...

Michiel Bakker, President of the Culinary...

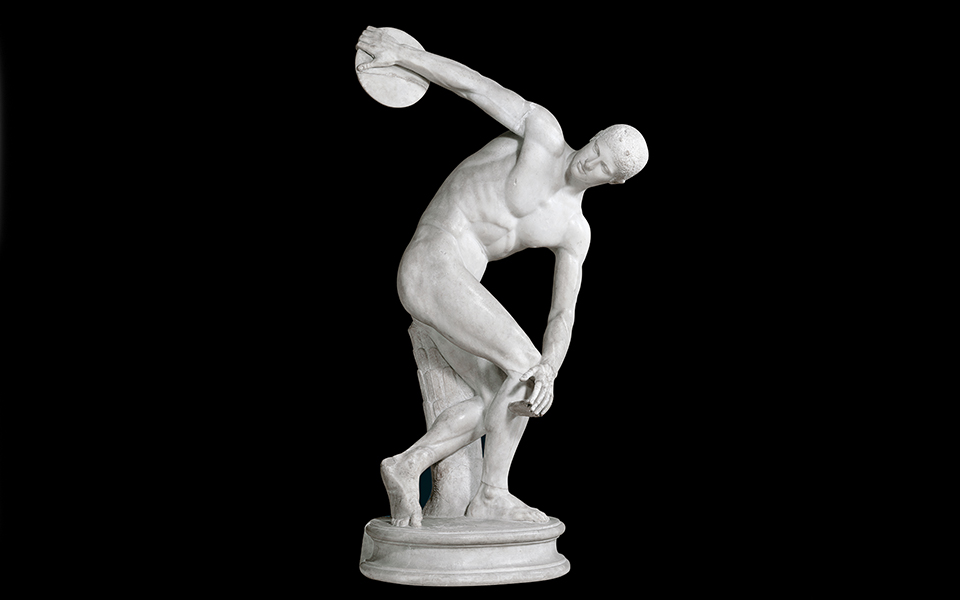

The Discobolus (Discus thrower); a copy (1st c. BC) of a famous statue (460-450 BC) by Myron (Vatican Museums, Rome).

© Hellenic Ministry Of Culture And Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund, National Archaeological Museum, Athens/J.Patrikianos

Although the scientific basis for the indispensability of regular exercise for health and well-being is a relatively recent development, knowledge of this fundamental link dates back to the ancient Greeks. Two physicians by the names of Hippocrates (460-370 B.C.) and Galen (129-210 A.D.) were the first to point out, merely by their powers of observation, the prophylactic as well as therapeutic value of exercise. The magnitude of their discovery was such that their teachings dominated medical education and thought for almost 15 centuries.

Current research evidence has proved unequivocally that regular exercise is essential for one’s sustained well-being. Insufficient exercise is not only detrimental to the overall functions of the body, but also contributes to multiple chronic health disorders, such as Type 2 diabetes, colon cancer, coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke.

Hippocrates, who is universally honored as the father of medicine, was the first to introduce the revolutionary notion that diseases arise either from excessive food or too much exercise, and when the two are balanced this leads to good health. In Book 1 of his On Dietetics (Περί Διαίτης), he notes:

“Eating healthily by itself will not keep a man well; he must also have physical exercise. Food and exercise, while possessing opposite properties, nevertheless mutually contribute to maintaining health. It is the nature of exercise to draw on the body’s materials, while it is the nature of food and drink to restore them. It is necessary, as it appears, to determine the exact powers of various exercises, both natural and artificial, and which of them contribute to the development of muscle and which to wear and tear. Furthermore,one must proportion exercise to the quantity of food, to the predisposition of the person, to his age, to the season of the year, to the changes of the winds, to the geographical place in which the person resides, and to the climatic conditions of the specific year.”

A long jumper performing his event, depicted alongside a musician playing the diaulos (double-flute), judges and other athletes; Attic red-figure kylix, 480 BC (Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig, Basel).

Reading Hippocrates is more or less like reading a modern textbook on Ergophysiology, the modern scientific field that deals with the nature of exercise stimuli, biological adaptations to muscular effort and, by extension, the optimization of human performance.

It is fascinating that Hippocrates was able to discover, twenty-five centuries ago, what our latest scientific findings in Genomics have confirmed today about the importance of individualized exercise for the improvement of health and fitness.

This is exactly the same discovery at which Galen arrived later on, a discovery which has revolutionized today the entire field of Ergophysiology. Galens’ dictum states that:

Not all bodily movement is exercise.

Galen, without a doubt, was the most influential physician that ever lived and could be considered the forefather of Ergophysiology. By incorporating the teachings of Hippocrates he was able to systematize, for the first time, the prevailing ancient knowledge on the function of the human body during exercise. In Book 1 of his On Hygiene (Υγιεινά), he observes:

“To me it does not seem that all (bodily) movement is exercise, but only when it is vigorous; but since vigor is relative, the same movement might be exercise for one and not for another. The criterion of vigorousness is alteration of breathing; those movements that do not alter the respiration are not called exercise; but if anybody is obliged by any movement to breathe more or less or faster or more frequent, that movement becomes exercise for him. This is what is commonly called exercise.”

In the same way, physicians and exercise scientists around the world today, when prescribing an exercise for health, make a clear distinction between simple bodily movement and exercise. While physical activity can be considered any bodily movement that results in energy expenditure above resting level, exercise is a planned, repetitive and purposeful physical activity aiming at the improvement or maintenance of health and fitness.

Our bodies are designed to be active and, despite the mounting evidence for the value of physical activity, people spend very little time being active at work, at home, or during transport and leisure activities. It is estimated that during the last half of the 20th century, daily energy expenditure for city dwellers has decreased about 800 kcal, which is equivalent to daily walking of about 15 km. Thus, sedentary behavior is so widespread in modern society that it has reached epidemic proportions, with harmful consequence to health functioning and well-being.

Runner depicted on a black kylix (wine-drinking cup) from Corinth, circa 570-560 BC (National Archaeological Museum, Athens, photo: E. Miari).

But why—one may ask, with respect to both modern and ancient times—should we exercise? Again, Hippocrates gives a clear-cut answer to this question, in Book 2 of his On Dietetics, where, in only a few lines, he encapsulates most of the health benefits of exercise! “Nowadays, based on mounting and compelling evidence, major medical and scientific organizations recommend that children and adolescents, young and middle-aged adults, older adults, and those with chronic conditions should engage in regular physical activity in order to improve overall health and fitness, to protect themselves from the harmful effects of physical inactivity and to delay the aging process.”

Strong evidence from research shows that physical inactivity is a risk factor for dying early from the leading causes of death, while regular physical activity benefits the heart, invigorates and improves brain function, stimulates growth and development, improves immune function and affects the aging process.

This is, in fact, what Galen also noted in Book 5 of his On Hygiene. He observed that, although exercise cannot stop the aging process, it can certainly delay it; thus, he proposed that the elderly need not be less active than the young. This finding is confirmed today by a large number of longitudinal, cross-sectional and experimental studies that clearly stress the importance of regular exercise on the aging process: “Older adults who exercise regularly are aging better; they produce adaptations that enable them to perform activities in their daily lives and to sustain submaximal muscular work with less cardiovascular stress and muscular fatigue than sedentary people.”

Consequently, as a rule of thumb, older adults should avoid inactivity and always keep in mind that some physical activity is better than none. Regular exercise is essential for living longer and aging better and should include two main modalities: aerobic and strengthening exercise.

Further reading

For an update on Exercise & Health and for integration of physical activity into our daily lives, refer to: Physical Activity 2016: Progress and Challenges, The Lancet (July 27, 2016).

Michiel Bakker, President of the Culinary...

A closer look at the powerful,...

We discover the healing properties of...