The Delphic Idea – Eva Palmer-Sikelianos and Angelos Sikelianos

Eva Palmer’s love affair with the culture of ancient Greece began even before she first saw Greece, or met the poet Angelos Sikelianos. A magnificent account by Professor Artemis Leontis, Eva Palmer, a Life in Ruins (Princeton University Press, 2019) brings to light Eva Palmer’s contribution to the culture of modern Greece, both in collaboration with Angelos Sikelianos and in her own life and work.

In the first decade of the 20th century, Eva, a wealthy and well-educated American woman, was already promoting the embrace of ancient Greek culture through interpretations – both in life and in art – of the work and philosophy of Sappho in the intellectual lesbian circles of Paris. It was in Paris that she met Raymond Duncan (brother of the avant-garde dancer and choreographer Isadora) and his wife Penelope Sikelianos. Together, the three made ancient Greek clothing, using traditional weaving methods. A hand-loomed chiton would become Eva’s daily dress, which she wore unpretentiously and with great conviction throughout her lifetime. Her archaic clothing, made by her own hand, represented not only her devotion to an ancient Greek ideal, but also her embrace of pre-industrialized ways of living, a rejection of clothing that relied on labor that alienated the worker. Her work in fashion would become influential, and she would come to count the painter Tsarouchis among her apprentices.

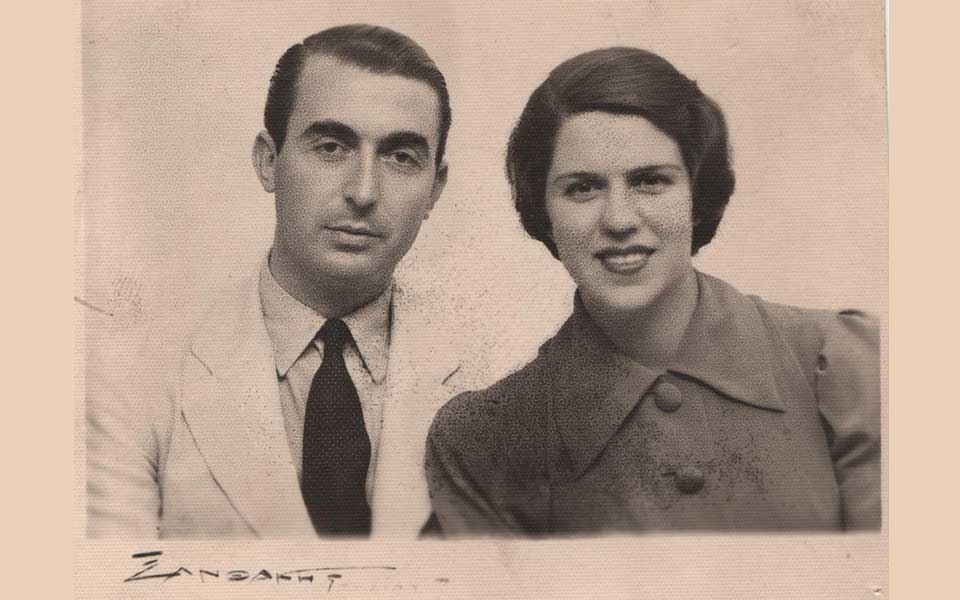

Greece was Eva’s inevitable destination, in every sense. Visiting Greece with the Duncans, she met Angelos Sikelianos, a poet and the brother of Penelope. With her ankle-length red hair, Eva presented an ethereal pre-Raphaelite beauty; for his part, Angelos (ten years her junior, he was 21 when they married in 1907) was striking; fine features were offset by an arresting gaze – in her words “une rayonnance, une transparence” (French was their mutual language). Their instant connection, however, transcended physical attraction. It was based on something more substantial and, ultimately, more lasting – their shared world view with peace and international fellowship at its heart. Apart from laying the foundation for their romance, this would also crystallize into what they called the “Delphic Idea.”

© Kostas Bournazakis Archive

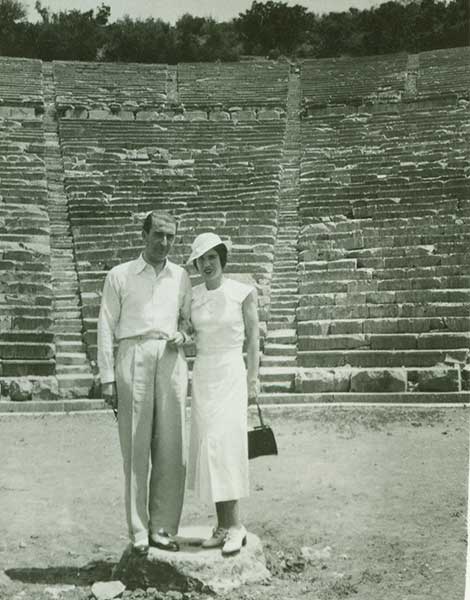

© Kostas Bournazakis Archive

The Delphic Idea centered on bringing people to the sacred area of Delphi to experience ancient Greek drama, poetry, athletics and discussion, all with the aim of gathering “the primordial seeds of life to revitalize humanity.” Sikelianos had originally shared what he then called a “Delphic Vision” with fellow poet Kostis Palamas in 1919. (Palamas died during the German occupation of Athens, and Sikelianos, in a historic moment for the nation, recited a rousing patriotic poem titled “Palamas” at his colleague’s funeral, inspiring the crowd of 100,000 to sing the National Anthem, not caring that this was prohibited). The Delphic Festivals of 1927 and 1930 – funded by Eva (which, in fact, put her in debt) – were the realization of this idea.

This was not a traditional epic romance; the couple’s physical intimacy would end in 1912, reportedly at the request of Eva. Ever unconventional, she proposed he take as mistress his cousin (their housekeeper), which he did for many years. There would be others.

The true love story here is Eva’s with Greece itself. Her more enduring romance with ancient Greece made a lasting mark on modern Greek culture. The Delphic Festivals, while a celebration of ancient Greek culture, were also very much of the moment, pivotal events bringing together key figures of what became known as the “Generation of the ‘30s” and which included such luminaries as the folklorist Angeliki Hatzimichali, the choreographer Koula Pratsika, the photographer Elli Seraidari (Nelly’s), the modernist architect George Kontoleon, and the painter and costume and theater designer Yannis Tsarouchis, for whom she was an important inspiration. The festivals highlighted the vast cultural reservoir from which Greek modernism derives its substantial depth.

For Further Reading: Leontis, Artemis: Eva Palmer, a Life in Ruins, Princeton University Press, 2019

The Salon of Athens – Leto and Angelos Katakouzenos

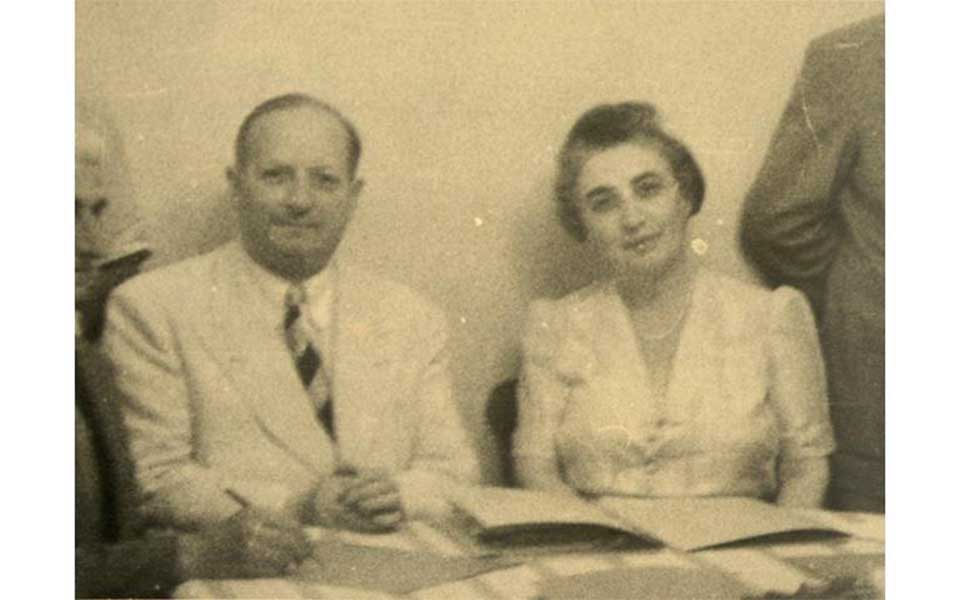

Arete-Leto Protopappa was born into the cream of Athenian society, her father a member of parliament during the tenure of Eleftherios Venizelos, her grandfather the founder of Greece’s first biscuit factory, and her great grandfather an aide-de-camp to King Otto. Her famously beautiful mother was a relative of Victor Emmanuel II, King of Italy. Leto, however, was not your typical society girl. First, there was her education in Berlin, Vienna, and Rapallo. She returned to Greece with a diploma in piano from the Berlin Academy of Music, and fluent in Italian, German, French and English. Then, there was her desire to contribute to society and culture, something more than merely making a good marriage. Angelos Katakouzenos, a graduate of medical school freshly returned from France, was dazzled and proposed to the young woman shortly after they met.

Leto went on to be active in the Greek resistance in WWII, as well as to pursue a career in letters, writing the highly successful The Luminous Path – the first play written by a woman to be staged by the National Theater, as well as two novels and two collections of short stories. Angelos was asked to open a psychiatric clinic at Evangelismos hospital, where he pioneered the use of narcoanalysis, a method for retrieving suppressed memories. Among his patients were prominent figures in the world of art and culture – both Greek and international.

Angelos and Leto were deeply devoted to art and culture. Their living room was one of the most interesting places in Athens, an intellectual salon that inspired creative discourse and debate. Nobel laureates Odyseus Elytis and George Seferis were both frequent guests, joined by international luminaries like Albert Camus, Arthur Miller, and William Faulkner. Greece’s finest painters were among their most intimate acquaintances, including Spyros Vassiliou, Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, Nikos Gounaropoulos, and Yannis Tsarouchis. Leto was something of a muse; Chagall painted her. And some of Hadjikyriakos-Ghika’s most beautiful work ever still hangs in that house: the doors that remain in situ – four panels celebrating the seasons. Tsarouchis and Leto had a marvelous relationship, and the artist left his mark on the dwelling; drawing on his extensive experience also as a noted stage designer, he made several inventive contributions to the Katakouzenos house.

Leto and Angelos’ love, and their art-filled life together, would last nearly half a century. After Angelos died in 1982, Leto penned a memoir titled Angelos Katakouzenos: O Valis Mou. The book, in turn, inspired a younger generation to organize, under Leto’s guidance, a series of discussions and events with leading figures of the Greek cultural scene. Leto died in 1997, but her salon, filled with magnificent works of art, each all the more precious for being a gift to the couple from the artist, is still a place of culture and inspiration, home to the Angelos and Leto Katakouzenos Foundation and the cultural events it sponsors.

For more information, and to visit the Katakouzenos House Museum, click here.

From Asia Minor to the Mataroa – Melpo and Octave Merlier

In the 1920s, Greece was both overwhelmed and profoundly enriched by the mass arrival of Greek refugees from Asia Minor. Close to 1,300,000 people arrived, bringing with them a vast cultural heritage. The musicologist and folklorist Melpo Logotheti-Merlier, seizing the moment, set about preserving some of it. It was a monumental task, but one she wasn’t facing alone; studying at the Sorbonne, where she presented her dissertation on Greek folk music, she had met Octave Merlier.

When the refugees began arriving, the Merliers were in Athens, where Octave worked at the French Institute. Melpo began to collect popular songs from all over Greece. The scope of her research then expanded to encompass the whole of the Asia Minor refugee experience, becoming the Asia Minor Folklore Archive. This vast archive of oral tradition was compiled by a dedicated team. The work unfolded over decades, ultimately encompassing 300,000 pages of interviews with some 5,000 refugees, all transcribed by hand.

This project, carried out with the support of the French Institute of Athens, formed the foundation for what is now known as The Centre for Asia Minor Studies – The Melpo and Octave Merlier Foundation, which is still active today.

When WWII began, a new chapter in the Merliers’ contribution to Greece and Greek culture would begin, with the Merliers’ activities in the Greek resistance. Octave had become the director of the French Institute in 1935. In 1941, the Merliers were captured and taken back to France by the Vichy government; Octave was a secret agent of Charles de Gaulle. They remained in the French countryside for three years. When they returned to Greece, and Octave resumed his role as the institute’s director, Greece was in turmoil; in the aftermath of the withdrawal of the occupying German troops, tension were breaking out between the monarchist right and British troops on one side and the EAM and ELAS – resistance fighters who had so recently been their allies against the axis – on the other. The escalation culminated in the “Dekemvriana,” armed clashes on the streets of Athens in December, 1944.

Against this background of bloodshed, Octave and his colleague Roger Milliex launched an ambitious initiative – to evacuate as many of the artists and intellectuals of Greece as they could to Paris. In the chaos of the era, the departure was delayed twice. Finally, on December 21, 1945, a ship set off from Piraeus with 200 young Greeks from a variety of fields. There were philosophers, poets, sculptures, architects, physicians, and directors. The ship was called the Mataroa, a name now synonymous in Greece with creativity and freedom.

For more information on the Center for Asia Minor Studies – The Melpo and Octave Merlier Foundation, click here.

For Further Reading: Asia Minor Hellenism: Heyday – Catastrophe – Displacement – Rebirth, edited by Evita Arapoglou, published by the Benaki Museum and the Centre for Asia Minor Studies.

© Takis Pananidis Archive

Greece’s Rousing Romantic Soundtrack – Manolis Chiotis and Mairi Linda

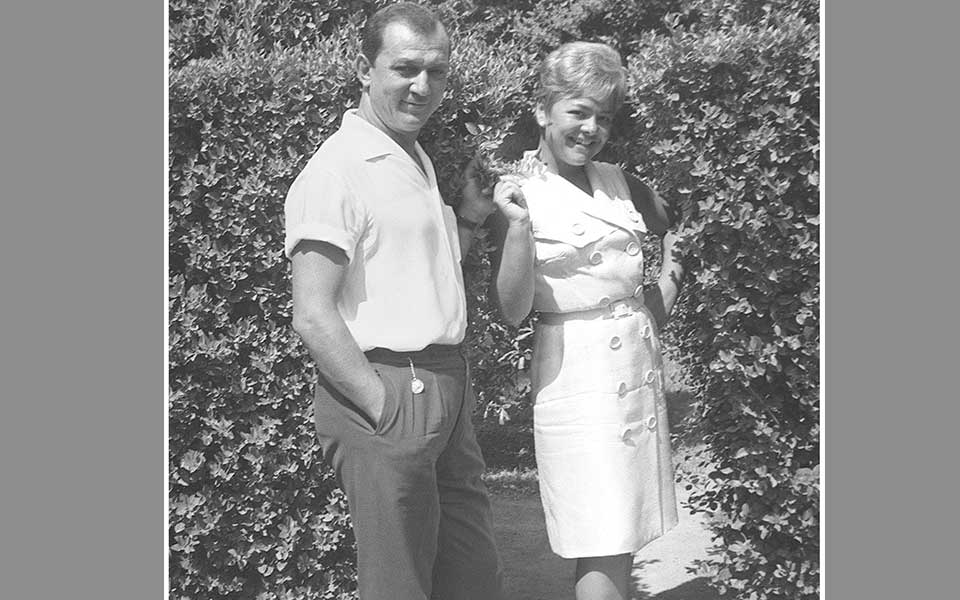

Mononyms are all that is necessary for this couple, household names now for a third generation of Greeks. Bouzouki player par excellence and composer in both rebetiko and laika (Greek popular music of the ‘50s -’70s) genres, Manolis Chiotis is thought to be one of the best bouzouki soloists of all time; his thrillingly fast passages are marked by the clarity of each note, while the captivating vocals of Mairi Linda (née Maria Dimitropoulou) have influenced a generation of singers.

Chiotis came to music and the nightlife it entails quite naturally; his mother ran one of the more elegant bars in Thessaloniki. At 16, he left for Athens, where he started playing in the music cafés, quickly making a name for himself. He was also an innovator; he is credited with popularizing the four-course bouzouki, the standard at the time being the three-course (a “course” is a pair of strings; the bouzouki has double strings).

Mairi Linda, younger than Chiotis by several years, would later sing in these same cabarets and music halls. These are the circles in which she met Chiotis, and they soon became a popular duet. Her singing was marked by a superb agility, precision, and a distinctive sense of phrasing. It was a magical combination musically (as is evident in “Αφου το θες” – one of their many, many hits), and for a time romantically; they were married from 1959 to 1966. The couple performed together, appearing as themselves, in nearly 20 popular films from the late ʽ50s through the mid-60s, a golden era of Greek cinema. As a duet, they created dozens of hits of enduring popularity.

One Single and Eternal Greece –Rallou Manou and Pavlos Mylonas

“Δεν υπάρχει άρχαία και νεα Ελλάδα, αλλά μόνον Ελλάδα, αιώνια, ζωντανή και ωραία” (Ελληνικό Χορόδραμα 1950-1960 1961, p8)

“There is no distinction between ‘ancient’ Greece and ‘modern’ Greece – there is just one single and eternal Greece, beautiful and palpitating with life.”

The choreographer Rallou Manou was a pivotal figure in the thriving cultural scene of mid-century Greece. Beginning as a student of dance with Koula Pratsika, she broadened her exposure to contemporary currents in dance with studies in Paris (1934), then Munich (1935-37). After the war, she took a troupe to Paris to perform folk dances in traditional costume, accompanied by music on traditional instruments. In 1947, she visited the school of Martha Graham in New York.

The cumulative power of these experiences, united with her vision of the unity of Greek culture, would soon find its expression through the Helleniko Chordrama (Greek Dance Drama), which she founded in 1951. Her all-encompassing response to the quest for Greekness at the heart of the artistic movement known as the “Generation of the ‘30s” involved a synthesis of various aspects of Greek identity – ancient drama, folk culture, and Byzantine tradition – expressed through the vocabulary of modern dance.

This “Gesamtkunstwerk” of Greekness involved collaboration with the most dynamic artists and intellectuals of her generation, among them the composers Manos Hadjidakis and Mikis Theodorakis, the shadow puppet artist Eugenios Spatharis, the painters Yannis Tsarouchis, Yiannis Moralis, Spyros Vassiliou, and Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, the writers Odysseas Elytis and Nikos Kazantzakis, and the director Michael Cacoyiannis. She would also collaborate with international artists, and represented Greek culture abroad, touring with her works in the Balkans, Egypt, South Africa, Iran, the US, and the Soviet Union.

Her husband, the architect Pavlos Mylonas, achieved through his work what Manou did through hers: giving modernist artistic expression depth, identity, and cultural relevance. Joining other noted architects of his generation such as Dimitris Pikionis and Aris Konstantinidis, Mylonas was a strong proponent of critical regionalism: giving modernist buildings a sense of place in response to both their natural setting (landscape and light) and their cultural context. This resulted in a specifically Greek modernism, a regional response to an international architectural style.

Mylonas, architect and professor at the Athens School of Fine Arts, was truly a scholar. His study in photographs and drawings of the neoclassical and eclectic buildings of Athens and of examples of its vernacular architecture spanned four decades. He also compiled a vast archive detailing the architecture and the topography of Mt Athos, the work of countless visits over his lifetime.

This intimate familiarity with Greek vernacular architecture added depth to his work, resulting in an approach to modernism that incorporated cultural identity while also responding to the natural environment. His buildings of note include the Mt Parnes Hotel, a high-profile project on Mt Parnitha for EOT, the National Tourism Organization of Greece.

Mylonas was acquainted with many of the era’s most interesting artists. He collaborated with them as Manou did through the Helliniko Chorodrama. For the Mt Parnes Hotel, he incorporated a notable work by Yiannis Moralis, while the pool garden, with original rocks left in situ, was the work of Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika. He also designed the Officers’ Club of Thessaloniki, one of the city’s most prominent buildings, located across from the White Tower; its unusual concave façade seems to communicate directly in form with the round tower, while his playfully modernist handling of volume and his cantilevered balcony serve as a modernist response to the 15th century monument. The unexpected use of deep red and raw golden stone help to further emphasize the connection to the city’s Byzantine heritage.

Another interesting work is the one he did for himself: Rallou House. The couple, close with nearly all the key figures of contemporary culture, had collaborated a number of times with the painter Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika. When Ghika engaged Mylonas to design a studio for him at his home on Hydra, the architect became enchanted with the island. He bought a number of small adjacent traditional houses above the port and, after restoring them, connected them to create a single beautiful home, named for his wife. It’s there still, and sometimes available for rent.