Kypseli: 18 Stops for Food, Coffee and Drinks

Old and new hangouts, cafés, sandwich...

The Propylaia, the monumental gateway to the sacred precinct of the Acropolis, was built between 437 and 432 BC.

© George Pachantouris/ Getty Images/ Ideal Image

The Acropolis of Athens stands as one of the most recognizable landmarks in the world, an enduring symbol of Classical Greece, European culture, and of the social and political achievements of the ancient Athenians, the progenitors of Western democracy. The Acropolis and its spectacular monuments, collectively inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1987, represent the single largest concentration of Classical Greek art and architecture on the planet. It’s no surprise, therefore, that it is the most visited archaeological site in Greece, hosting as many as 16,000 people per day during the summer months.

The word “Acropolis” means “high city” (“akron” meaning “highest” or “extreme,” and “polis,” meaning “city”). It dominates the Greek capital’s skyline, offering some of the best views of the city and its surrounding mountains, the Athenian Riviera to the west, and the nearby islands and coastlines of the Saronic Gulf.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the main monuments and features of the Acropolis of Athens and why it a must-see destination, and offer some fun tips on what to look out for when you visit.

Built on an enormous 70-million-year-old rock outcrop, the monuments of the Acropolis represent the largest concentration of Classical Greek art and architecture in the world.

© Shutterstock

One of the most striking things about the Acropolis is its remarkable geology, which consists of two distinct layers of rock, one on top of the other: limestone, and a mix of sandstone and marl, known as “Athens schist.” This lithographic pairing is an erosional remnant of a thrust sheet, otherwise known as a “klippe,” the result of a highly complex process of plate tectonics. Rising 150m above sea level, the upper layer that caps the Acropolis is referred to as “Tourkovounia limestone,” and was deposited sometime towards the beginning of the Late Cretaceous, around 100 million years ago. The sandstone/marl layer beneath, somewhat bizarrely, is estimated to be around 30 million years younger; in other words, the upper layer of rock is older than the lower layer!

Interestingly, there is a third layer of finely grained cataclastic limestone that separates the two main units, forming a narrow horizontal fault line that runs through the Acropolis (see if you can spot it in the soft, rosy glow of the late afternoon light). Geologists argue this layer of crushed up rock acts as a “buffer” in the event of earthquakes, a daily occurrence in Greece, thus providing the ancient monuments atop the plateau with some cushioning against continuous seismic activity.

In the past, the outcrop would have been much larger. Since its formation some 70 million years ago, it has undergone steady erosion from the sides, the sandstone/marl layer being more susceptible to weathering.

Agents of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, removing sculptures from the Parthenon in the early 19th century.

© © IN SEARCH OF GREECE. CATALOGUE OF AN EXHIBIT OF DRAWINGS AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM BY EDWARD DODWELL AND SIMONE POMARDI FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE PACKARD HUMANITIES INSTITUTE, 2013

The first known inhabitants of the Acropolis can be traced back to the 4th millennium BC, during the Middle Neolithic (“New Stone Age”). Careful investigation of the archaeological deposits in the caves that pockmark the sides of the outcrop attest to the presence of small groups of subsistence farmers, the flattish plateau providing them with the perfect vantage point to keep watch over the surrounding landscape.

The first fortification walls were built around the summit of the Acropolis during the 13th century BC, towards the end of the Late Bronze Age. These enormous “Cyclopean” walls, so-called because the Classical Greeks believed they were built by giant one-eyed monsters, were 760m long and up to 10m in height, and encompassed a Mycenaean palace that formed the main political and economic center in the region. Nothing of this palace remains today except a single limestone column base and fragments of several sandstone steps, but it was clearly a vast complex. A literary reference to the Mycenaean-era citadel appears in Homer’s “Odyssey” (7.81): “the well-built house of Erectheus,” the seat of a semi-mythical early king of Athens. It is interesting to note that while all the other Mycenaean centers in mainland Greece, including Mycenae itself, were destroyed and/or abandoned around 1200 BC, the palatial site at Athens remained inhabited and active.

Later, in the 8th century BC, the Acropolis gradually took on a more religious character with the establishment of a cult to Athena, the city’s patron goddess. Little is known of the architectural monuments of this period, except that a sacred precinct or altar developed into an important religious sanctuary by the mid-6th century BC, and the Acropolis itself became known as the “Sacred Rock.” During this time, a massive limestone temple to “Athena Polias” (literally “Athena of the City”) was erected, a forerunner to the Parthenon. Described as a “Hekatompedon” (or “hundred–footer”), some of its sculptural and architectural elements can still be seen today in the Archaic Gallery of the nearby Acropolis Museum.

In the last quarter of the 6th century BC, another temple of Athena was built, the foundations of which were discovered between the site of the later Erechtheion and Parthenon temples in the late 19th century. Referred to as the Old Temple of Athena or the “Achaios Neos,” it housed a wooden cult statue (“xoanon”) of the goddess, but was destroyed, along with all the other buildings and shrines on the Acropolis, by the invading Persians in 480 BC. Debris from the Old Temple was reused in the reconstruction of the citadel’s fortification walls in the years immediately following the allied Greek victory over the Persians.

The spectacular monuments we see on the Acropolis today are the result of an ambitious building program, which started in the middle of the 5th century BC. Spurred on by their stunning victories over the Persians at the Battles of Marathon (490 BC), Salamis (480 BC), and Plataea (479 BC), the Athenians gradually assumed political, economic, and military dominance of the ancient Greek world, ushering in a “Golden Age.” Under the leadership of the great statesman and general, Pericles (c. 495-429 BC), Athens was at the forefront of the cultural arts, literature, theater, philosophy, and, of course, architecture. Renowned for his immense oratorical skill, Pericles continued to foster Athenian democracy, extending citizen’s rights and public services, and was keen to showcase Athenian social and cultural supremacy via a spectacular building program of civic and religious monuments on the Acropolis.

The Parthenon (temple of Athena Parthenos, the “Virgin”), the Propylaia (monumental gateway to the sacred precinct), the temple of Athena Nike, dedicated to the goddesses Athena and Nike (“Victory”), and the Erechtheion, noted for its beautifully elegant columns in the form of young maidens (Caryatids), were all conceived in the Periclean building program of the second half of the 5th century BC, designed and built by a remarkable group of architects and sculptors. The result of their work transformed the outcrop into a religious complex of unrivaled scale and beauty, the ultimate expression of Classical Greek art.

The monuments of the Acropolis, still standing after nearly 2,500 years of wars and invasions, bombardments, fires, earthquakes, and the looting of its decorative sculptures (most notoriously, Lord Elgin), not to mention the countless alterations and adaptations by various occupying powers over the centuries, continue to evoke bewilderment and awe in equal measure. No visit to Athens – or Greece for that matter – would be complete without spending at least a few precious hours exploring these timeless wonders.

Both entrances to the Acropolis can be found at either end of Dionysiou Areopagitou pedestrian street.

© Shutterstock

Located in the heart of downtown Athens, you can access the Acropolis on foot, by bus, or by Metro. One of the best options is to take the Metro to “Akropoli” station, conveniently located right next door to the Acropolis Museum and the first of two entrances to the archaeological site of the Acropolis, on Dionysiou Areopagitou pedestrian street (simply follow the signs as you exit the station). The larger, main entrance, located at the foot of the western slope, is at the far end of the same street, near Filopappou Hill.

Another option is to take the bus to “Makrigianni,” which is only a short walk away from the smaller entrance on the southeast corner. Both entrances can be notoriously busy during high season, so plan accordingly.

It should be noted that a specially designed elevator has recently been installed on the northeast side of the Acropolis, providing access for visitors with mobility issues. A concrete path was also built around the site in 2021, making it more wheelchair friendly.

For more information on how to visit the Acropolis, including accessibility, ticket information and opening hours, check out our handy guide here.

For early birds, the best time of the day to visit the Acropolis is at 08:00, as soon as the site opens. Large tour groups tend to arrive later in the morning, from around 10:00-ish, so, if you’re lucky, you’ll have the site more-or-less to yourself for a couple of hours.

In the summer months, between June and September, an early start is advisable to beat the intense midday heat (and the crowds), but if you do find yourself exploring the monuments at this time, be sure to pack enough water, wear suitable footwear, sunglasses, and hat, and apply plenty of sunscreen.

Another good option is to arrive a couple of hours before closing time (20:00 in the summer, typically April 1st-October 31st; 17:30 in the winter, November 1st-March 31st). At this time, you’ll be treated to the gentle glow of the late afternoon sun, casting shadows on the crystalline white marble of the monuments. It’s at this time of day the decorative sculptures on the buildings come alive with subtle ripples of movement. Magical.

The number of tourists in Athens drops significantly in October, so, if you can, do consider traveling out of season. In drizzly and overcast conditions, which are relatively rare, even in winter, take care not to slip on the marble surfaces or stairs. It is advisable to wear a good pair of rubber-soled shoes.

It is important to note that the monuments of the Acropolis have been undergoing extensive and almost continuous restoration since the mid-1970s. As such, you will likely see large sections of scaffolding and/or cranes alongside the Parthenon and other buildings during your visit. These may partly obscure the view of the monuments, but they certainly won’t dampen the atmosphere of exploring the site.

The monuments on the Acropolis are made almost entirely of Pentelic marble, quarried from nearby Mount Pentelicus, 16km northeast of Athens.

Today, no two structures on the Acropolis overlap, each with the appearance of an individual monument set against the Attic sky, but it would have looked very different in antiquity. From the 6th century BC onwards, we know that much of the sacred precinct was filled with marble statues and brightly painted ceramic vessels on bronze tripod bases, each one a dedication from a well-to-do inhabitant of the city, cluttering the spaces between the buildings and shrines.

The monuments can be divided into two areas: the Acropolis and the slopes. On the plateau, the Classical-era monuments consist of the Propylaia and the world-famous Parthenon, which were built first, and the temple of Athena Nike and the Erechtheion, both completed during the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC). The two monuments of the south slope include the Roman-era Odeon of Herodes Atticus, completed in 161 AD, and the Theater of Dionysus, which reached its fullest capacity in the 4th century BC.

Built almost entirely of white Pentelic marble, the architecture of the Propylaia (437-432 BC) is a combination of the Doric and Ionic styles.

© InTime News

As you ascend the western slope of the Acropolis from the main entrance, the first monumental building you will encounter is the Propylaia, meaning “Gates.” Designed by the architect Mnesikles and constructed between 437 and 432 BC, it served as the ceremonial gateway to the sacred precinct. Approached from the west, the U-shaped, tristyle gateway consists of a colossal central hall with towering columns, through which passed the processional route to the plateau, flanked by two outward projecting wings to the north and to the south.

The Propylaia was cleverly designed to fit the steep incline of the hill and featured a zig-zag ramp that led up to the central hall, still visible today. As you make your way up the stairs, to the left you will observe the north wing, known as the “Pinakotheke” (or “picture gallery”). According to some scholars, this was used as a ceremonial dining hall, and was described by 2nd century AD Greek traveler Pausanias as “a chamber with paintings,” featuring a number of works by renowned Classical-era artists.

Built almost entirely of Pentelic marble, it features both Doric and Ionic architectural styles, and was a source of inspiration for designers and architects of later periods, notably the Roman-era Greater Propylaia at Eleusis, from the late 2nd century AD, and the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, a neoclassical monument built in the late 18th century.

The Propylaia was heavily damaged during the Venetian bombardment in the 17th century and later underwent restoration during the 19th century. As you pass through the central hall, be sure to look up and see the extraordinary ceiling structure, featuring coffer panels, which would have been elaborately decorated, 6m-long marble beams, and two reconstructed Ionic column capitals.

The Temple of Athena Nike, completed around 420 BC, was built as a monument to Athenian military prowess.

Before you pass through the central hall of the Propylaia, cast your eyes up and right to see a small, elegant structure with four Ionic columns (“tetrastyle”) at the front and rear, standing on top of the steep bastion wall. Designed by the master architect Kallikrates, and finished around 420 BC, this diminutive temple was dedicated to the goddesses Athena and Nike, the personification of Victory (or, more accurately, the goddess Athena in the form of Victory).

The Temple of Athena Nike is fully Ionic in style, the first of its kind on the Acropolis, and, like the Parthenon, featured an exquisitely carved frieze, a decorative relief sculpture that ran around all four sides of the building’s entablature. The east frieze, above the temple’s main entrance, depicted an assembly of the gods Athena, Zeus, and Poseidon, while the other three sides showed battle scenes, including the cavalry charge at the Battle of Marathon, and the final victory over the Persians at the Battle of Platea. What you see affixed to the temple today are copies. Fragments of the original frieze are currently exhibited in the Acropolis Museum and the British Museum in London.

The inner temple, or “cella,” would have housed a cult statue of the goddess, although what form it took remains open to speculation. Scholars have hypothesized that it was made of wood or bronze instead of marble, and with elements of gold and ivory. Nike was often depicted as “winged victory,” with Athena taking this form as a representation of the city being victorious in war. Built during the long and bloody Peloponnesian War against the Spartans, the temple would have played an important role in the religious and civic life of the Athenians, a symbol of the city’s military strength and imperial power.

The temple has undergone major reconstruction works in recent decades and is currently closed to visitors.

Built for eternity, the Parthenon (447-438 BC) is one of the largest Doric temples of Classical antiquity. The estimated 13,400 blocks of marble used in its construction were transported 16km from the quarries of Mount Pentelicus.

© Shutterstock

Without question, the crowning glory of the Athenian Acropolis is the Parthenon. Built between 447 and 438 BC during the height of the Golden Age of Pericles, the colossal temple was designed by the architects Iktinos and Kallicrates, while the master sculptor Pheidias was responsible for overseeing its exterior and interior sculptural decoration.

The Parthenon was dedicated to the goddess Athena Parthenos (the “Virgin”), the patron deity of the city. Constructed using Pentelic marble, the temple’s stylobate, or base, measures 73m by 34m, and its entablature, or upper portion, reaches a height of nearly 14m. The building was surrounded by a colonnade of Doric columns, with eight columns on the east and west ends and 17 columns on the north and south sides. Upon its completion, it was the largest and most lavishly decorated temple in mainland Greece.

The temple’s pediments, or triangular attic spaces, were decorated with brightly painted sculptural reliefs depicting scenes from Greek mythology. The east pediment depicted the birth of Athena from the head of her father, Zeus, while the west pediment showed the contest between Athena and Poseidon over the patronage of Athens. The 92 metopes, rectangular panels located above the colonnade, also featured scenes from mythology, including the gods and heroes of the Trojan War, the Centauromachy, the Gigantomachy, and the Amazonomachy. The most unique element was the temple’s decorative art was its 160-m-long frieze, depicting the Athenians themselves in the Panathenaic Procession, a sacred festival in honor of the birth of Athena. For more information on the architectural anatomy and decorative features of the temple, click here.

A recreation in modern materials of the lost colossal statue of Athena Parthenos by Alan LeQuire (1990). It is housed in a full-scale replica of the Parthenon in Nashville’s Centennial Park. She is the largest indoor sculpture in the Western world.

© Dean Dixon / Public domain

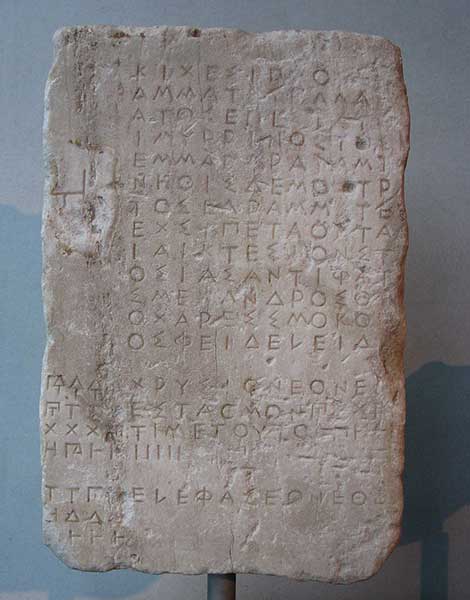

The ancient Greek inscription containing an account of the supervisors for the construction of the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Athena, 440/439 BC. New Acropolis Museum, Athens

© Tilemahos Efthimiadis / Public domain

The Parthenon also housed an enormous statue of Athena, made of gold and ivory (chryselephantine), and measuring 26 cubits high (approximately 11.5m), about a meter and a half from the ceiling. The statue was created by Pheidias and cost 704 talents to build, the equivalent cost of constructing 200 triremes (oared warships) from scratch!

The Parthenon has suffered catastrophic damage over the last 25 centuries, including a fire in 267 AD that destroyed many of its interior features and the original roof. In the 5th century AD, it was converted into a Christian church, and later into a mosque during the period of Ottoman rule. In 1687, during a war between the Venetians and the Ottoman Turks, the Parthenon was severely damaged when a Venetian mortar shell, fired from the nearby Filopappos Hill, stuck the building, and ignited the gunpowder that was being stored inside. Four columns on the south side are only partially restored, showing where the mortar shell entered the temple. To learn more about the Parthenon’s turbulent history, click here.

As you walk around the four sides of the temple, take note of its remarkable optical refinements, including the almost complete absence of any straight lines. At first sight, the temple appears to be a giant rectilinear construction, but you’ll notice that virtually all the horizontal and vertical surfaces are subtly curved, including the inward leaning columns and the slightly domed stylobate (base). Architectural historian Manolis Korres, one of Greece leading scholars on the Acropolis, once remarked that the perfectly proportioned Parthenon could support the entire weight of the US aircraft carrier “Nimitz,” adding: “The ancients built for eternity.”

View of the Erechtheion (conventionally 421-406 BC), with its famous southern Porch of the Caryatids. Replicas stand in for the original maidens, who (except for one in the British Museum) now reside in the Acropolis Museum.

© Shutterstock

Perched atop uneven ground on the north side of the Acropolis, the Erechtheion is perhaps the most striking monument on the Sacred Rock. Designed by the architect Mnesikles and built in the last 20 years of the 5th century BC (although more recent scholarship favors the 430s), the temple replaced the older “Achaios Neos” of Athena Polias, which was partly destroyed by the Persians 60 years earlier. Based on a description of the temple by Pausanias, its irregular layout stems from the fact that Mnesikles had to incorporate multiple shrines within the building: an eastern chamber, dedicated to the cult of Athena, and a lower, west-facing chamber, housing individual shrines to Poseidon-Erechtheus, after whom the temple is named, Hephaistos, the god of fire and metallurgy, and Boutes, the brother of Erechtheus.

The most outstanding feature of the Erechtheion is its south-facing marble porch, known as the “Porch of the Caryatids,” consisting of six female figures (“korai”) carved in the form of columns, supporting the roof. Made of brilliant white marble from Paros, each of the caryatids is unique, with her own flowing robes, pose, and hairstyle. What you can see today are replicas, five of the originals being in the Acropolis Museum, while the sixth, looted by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century, is on display in London at the British Museum.

Other notable features of the Erechtheion include the sacred olive tree of Athena, which can be found behind the north porch (according to legend, the current tree, planted in the early 20th century, is a descendant the sacred tree of the goddess). As you walk around the north porch, look up at the ceiling and see if you can spot the missing coffer panel. In the myth, this is where Poseidon’s trident pierced the building and struck the ground, leaving cut marks in the bedrock below.

More information on the Erechtheion can be found here.

The Theater of Dionysus, on the south slope of the Acropolis.

© Public domain

As you make your way down the south slope, you will see the well-preserved remains of the Theater of Dionysus, dating to the 5th and 4th centuries BC. At its height, the theater hosted the famous “City Dionysia” festival in honor of Dionysus, god of theater, religious ecstasy, wine, and fertility. Part of the festival involved a procession of citizens carrying large phalloi (absurdly oversized male genitalia), but the main events were theatrical performances of dramatic tragedies and, later, comedies. The theater had a capacity of 25,000 by the 4th century BC and remained in continuous use until well into the Roman period.

The Roman-era Odeon of Herodes Atticus was built in 161 AD.

© Shutterstock

Also on the south slope, near the Propylaia, is the Roman-era Odeon of Herodes Atticus, built in 161 AD by the prominent Athenian nobleman and philanthropist Herodes Atticus (c. 101-177 AD). He commissioned the stone theater in memory of his late wife, Aspasia Annia Regilla, who had recently died in childbirth.

The original theater had a wooden roof, a three-story stone wall (still standing), and a capacity of 5,000, before it was partially destroyed by invading Heruli (a Germanic tribe, referred to by the Romans as “Scythians”) in 267 AD. It was heavily renovated in the 1950s using Pentelic marble.

Since 1955, the Odeon has been the main venue of the annual Athens Festival, hosting musical performances and other events by acclaimed Greek and international artists from June through August. If you find yourself in Athens during this summer, check out the artistic schedule on the official website.

Old and new hangouts, cafés, sandwich...

The Kerameikos archaeological site provides a...

Discover five of Athens’ latest openings,...

From ancient steam engines and living...