Before the opening of the Egnatia highway in 2009, Epirus was cut off from the rest of Greece. The airport at Ioannina, often blanketed in fog, has regular flight cancellations. Most residents tell stories of desperation and being trapped in the snow at the Katara Pass, or of the difficult and time-consuming journey to Athens. But the latter is now a breeze since 2017 with the Ionia highway. It took the Kathimerini team just four hours to reach Ioannina from the capital.

People from Epirus, who had been stranded alone on the Greek border, suddenly saw their region become a north-south and east-west hub, with Igoumenitsa upgraded as a sea gateway to Europe. As Greece was plunged into an economic crisis in 2010, a new era of optimism began in this remote area after centuries of poverty, typical of people living in isolation. How will the coming extroversion change the firmly rooted Epirus identity? This was the question that sought an answer against the backdrop of the lake.

© Nikos Kokkalias

“Living here since 1999, I have seen the city change for the better. Tourism is revitalizing Ioannina, Zagori and Tzoumerka,” says Nora Tsoga, an Athenian who built an elegant boutique hotel called Lake Spirit in 2017 with her husband, whose family is from Ioannina.

“The economic crisis brought many young people back to their hometowns. With the improvement of economic conditions, others from abroad came to merge in the best way with the society that is now opening up to the world despite having had trouble adapting to changing new conditions in the past. These cosmopolitan 30-somethings will be the spearhead of progress. I am very optimistic. I have only one concern. That the bad precedent of ‘development’ that we saw when mass tourism came to the Cyclades and elsewhere does not happen in Ioannina. Airbnbs have already proliferated. Rents are rising. But knowing the people of Ioannina, I know that they have an inner sense of moderation and a tremendous love for their land that will protect them from the greed that has destroyed other places.”

© Nikos Kokkalias

© Nikos Kokkalias

Chef makes hot sand-brewed coffee

One of the young men who returned to Ioannina is 35-year-old Thanasis Tassos. He was born in Konitsa to parents who own a hotel and restaurant in the Bourazani Environmental Education Park. He studied in Athens, worked in Germany and returned to open the first creative cuisine restaurant in Ioannina, Thamon. We met him at his new venture, Erectus, where he cooks using crock pots buried in hot sand. The cabbage rolls (“dolmades”) and the pork dish with leek, celery and egg-lemon sauce that we ate were incredibly delicious.

“With Thessaloniki chef Ioannis Xristidis and the whole team at Thamon, we experimented with local ingredients, even making spoon sweets using giant beans. After a year and a half, we launched this new restaurant with a focus on tradition. People embraced us. Until now, the restaurants here were mostly just selling grilled meat. Along with tourism, the restaurant market opened up,” says the chef. “We need our roots to move forward, to keep what we have inherited, but we also need the old to make room for the new. We need a balance of boldness and respect from our generation. We are experiencing a jump in Ioannina. But we have to show wisdom, not to imitate what is done elsewhere, to make our own mark, to put our own signature to it, the Epirus signature. We must not rush, we must do everything right. For the success of the restaurant, I am most happy that I contributed a little bit so that other people from Ioannina who work abroad can come back.”

© Nikos Kokkalias

Another representative of this dynamic generation is 40-year-old Thanasis Navrozoglou, born in the United States to a Greek-American mother from Epirus and a father from Ioannina, who met there while studying computer science. When he was a child, in the 1980s, his parents returned with the intention of opening a computer store. “If you can find me three people who will buy computers in Ioannina, we’ll stay, otherwise we’ll go back to America,” his mother said to his father.

“We found the three and many more. They quickly developed programs for basic accounting functions, and one of their first clients was the Cooperative Bank of Ioannina [now Epirus],” he says. Natech, which he founded with his father, has grown to produce software for small banks with Greek and foreign clients, and is currently working with Piraeus Bank to create the country’s first all-digital bank.

“We are experiencing a period of great change in Ioannina, with the technological community taking its first steps. There are 500 people and companies that have come from abroad. For an ecosystem to grow properly, it needs financing from funds, something in which we are still lagging behind. It would also help a lot if there was a better connection with the university, because it acts as a talent incubator, but in practice it is difficult to have a partnership to move forward with what we call industrial PhDs. In other words, to produce new technologies that the market needs in collaboration with certain departments. Professors prefer to be involved in European projects rather than in such ventures. Sometimes I dream that Ioannina could become something like Zurich. There are many opportunities, but also many problems to be overcome for proper development.”

© Nikos Kokkalias

© Nikos Kokkalias

Vassilis Tsoukanelis, one of those responsible for the city’s economic progress and the appointed executive adviser of the Cooperative Bank of Epirus, fully agrees with this optimism: “Forty years ago, Ioannina was an administrative center, with civil servants and the army. Money came from students and the remittances of migrant workers. Today, it is a leader in the bottled water industry, poultry farming and dairy products. Roads made it easier to do business and export products. New technology companies have arrived, new restaurants are opening, we have year-round tourism. In the future, when the road to Albania is opened, tourism from Central Europe will come here. We are also waiting for the connection of the Athens-Thessaloniki highway with the Egnatia highway, at the level of Grevena. The airport of Aktion, which is seeing more traffic, will also benefit when Preveza is connected to the Ionia highway. We have two very good and large hospitals. All this offers an amazing quality of life and prospects that can bring even more visitors. And certainly new residents.”

Nomads of the lake

One night at one of the city’s bars, we met some of the foreigners at a networking event. They are part of a community of digital nomads from all over the world who work remotely in Ioannina as architects, programmers, designers, writers, biologists and more.

“There are about 25 of us, some of whom are married to locals, like myself,” says the oldest member of the group, Irene Maragos, a translator who grew up in Montreal. “What attracts most people is the beauty of the area, the lack of crime, the low cost of living so far. In my case, it was also the fact that my husband’s parents help raise our children. We are now preparing our first co-working space in a building provided by the city. This will give a new impetus for others to come.”

I asked a 70-year-old Belgian woman sitting next to me why she chose Ioannina. She surprised me: “I googled high mountains, sea, hospital, airport and up came Epirus! I packed my bags and came. It’s wonderful.”

© Nikos Kokkalias

As Aimilios Neos, the municipality’s tourism officer and a talented photographer, took us out on his small private boat to the lake’s island, he explained that there were very few permanent residents left on the little island, whereas when he was growing up, the place was bustling with life. Our stroll around the island left me speechless by its beauty: listening to the ducks, enjoying the distant view of the city amid the sound of outboard motors. The tour of the Byzantine monasteries with their stunning paintings was unforgettable. The Ali Pasha Museum, built thanks to the perseverance of a private citizen, Fotis Rapakousis, is also worth a visit. On the other hand, one could see the lack of taste and vision of the locals in the cheap souvenirs and in the totally touristy food offered in the tavernas. The flow of visitors to the island stops with the last run of professional boatmen, while the first guesthouse where a foreigner can sleep on the island is only just being constructed. As for us, we were lucky: We watched the crimson sunset while enjoying a meal prepared for us by 90-year-old Evdoxia, Aimilios’ mother. Zurich a la Greek.

© Nikos Kokkalias

“We will go on and not lose anything of our tradition,” Kostas Belevetis, who owns a famous tsipouradiko (a restaurant where along with your order of tsipouro, they bring you a small appetizer to taste) in the village of Katsikas, a 15-minute drive from Ioannina, told me resolutely. “My grandfather wore the traditional burazana and I wear sweatpants and sneakers, but the soul of an Epirus man remains the same,” he told me.

In front of us, the basketball game between Bayern and Baskonia was blasting on the television. At the same height as the screen, Kostas (as if in support of his opinion that Epirus is not threatened by globalization) had hung one of his grandmother’s needlework decorations, like an image frozen in time.

© Nikos Kokkalias

George Mousafiris, a silversmith of the same age as Kostas, had a different opinion. Ioannina is also known as the city of silversmiths and although the number of jewelry stores has increased, the number of artisans has decreased, he told us. There was so much jewelry around him that he looked like a painted icon in an Orthodox church surrounded by votive offerings: “There goes the work, it’s over. People have learned to buy what is easy and cheap. They don’t like the difficult and the expensive. That’s what I know, that’s what I do. How can I change at this age?”

© Nikos Kokkalias

Is something in danger of being lost in Epirus? Kostas Kakkos, 44, is a policeman but plays the clarinet professionally. He started with classical music, gave it up, then taught himself to play traditional songs.

“I learned how to play at festivals where old musicians still play; it’s like a school. I also learned from cassette tapes. I went to the shops around Omonia Square in Athens to buy them. The greats like Petros Loucas Chalkias had their own way of playing, you’d hear ‘foo’ and you’d know who it was. Each village had its own peculiarities and the musician was the bearer of a tradition. The listener was equally knowledgeable and a strict judge because the songs were passed down from generation to generation. At the festivals, the family would go and take a number so they would know when it was their turn to dance. And the clarinetist knew all the family members, what songs they liked, what problems they had, if someone had died, got married or was born. Even if he didn’t know them, he ‘read’ them in order to play correctly and earn his money. And if someone was dancing slowly, he knew which note to put in between until they put their foot down. Now we don’t play music, it’s like making ground beef. There are songs being released on YouTube all the time with infinite influences, the repertoire has gotten out of hand, it’s like a coronavirus spreading. As an audience you have hundreds of people like in the bouzoukia [the flashy nightclubs with live Greek popular music]. They don’t listen to the music with their ears, but with their eyes. The identity of Epirus is not threatened by new roads, but by cables and Wi-Fi.”

© Nikos Kokkalias

© Nikos Kokkalias

The weighty legacy of Elisaf

The stately mansion belonging to attorney Niki Lappa’s family served as the headquarters for Greek dignitaries during Ioannina’s liberation from the Turks: “Ioannina, initially steeped in puritanism, later embraced the ambiance fostered by its villagers. However, the Egnatia and Ionian highways ruptured this old order. Likewise, the election of Moses Elisaf, possessing the charisma and vision to revamp the city, marked a pivotal moment. Regrettably, he didn’t live to witness it. It was a profound loss for us.” How did a secluded society produce Greece’s first Jewish mayor? “They elected the Ioannina physician who for decades demonstrated integrity and devotion to his homeland. Not the Jew,” she recounted.

Ιn the historic gathering of Romaniote Jews, others would concur with her observation. Among those seated alongside me were Patra Elisaf, Moses’ widow, community leader Markos Batinos, General Secretary Periklis Ritas and Isaac Lagaris, an esteemed emeritus professor at the University of Ioannina. The Greek-speaking Romaniote Jews represent Europe’s oldest Jewish community, dating back to the 3rd century BC. In 1944, 1,870 Ioannina Jews were deported to Auschwitz, following German orders that encouraged the plundering of homes and seizure of assets. Only 181 returned, with 69 having fled to the mountains with partisan aid or hidden among Christians. Upon their return, many struggled to reclaim their properties and businesses. Today, their numbers have dwindled to fewer than 50 community members.

“My mother-in-law, Moses’ mother, upon her return to Ioannina from Palestine, where she had sought refuge, encountered a woman adorned with one of her jewels. Her only remark to us was, ‘I wish that you never associate with this woman,’” Patra recalls. I pondered if there had ever been a form of catharsis for the events of 1944-45. “We are a close-knit community; everyone knows who did what during that time. It’s a collective secret without ever mentioning names,” Ritas reflects. “On the other hand, the survivors were the silent generation. They couldn’t bring themselves to speak about the atrocities. They simply wanted to survive, to rebuild their lives with whatever means they had,” Batinos adds.

A notable figure from this community was Elisaf, a well-traveled, cultured pathologist and university lecturer. He provided free healthcare services twice a week at the university clinic and kept his phone line open 24/7 for those in need. “He never made his Jewishness an issue,” his wife remarks. “Some of his opponents appeared on television with religious imagery and the Greek flag as a backdrop. His election was a triumph for many. I’ll never forget an elderly woman who told Moses, ‘My doctor, I voted for you, then went to the priest and confessed.’” During his brief tenure, he spearheaded projects such as the restoration of buildings in the old city. Lina Mendoni played a pivotal role in this endeavor. The culture minister also addressed the issue of the Jewish cemetery, a portion of which has been designated as a historic monument.

We strolled between the verdant graves, resembling the white shells of ageless turtles. In 2009, there was an incident of desecration by unknown perpetrators who vandalized tombs and scattered ashes from the Auschwitz memorial crypt. At that time, a symbolic human chain was formed by citizens and representatives of organizations who offered massive support to the Ioannina Jews. Today, the community’s concern is the future: “What will become of the synagogue and the cemetery when the last of us departs from life?”

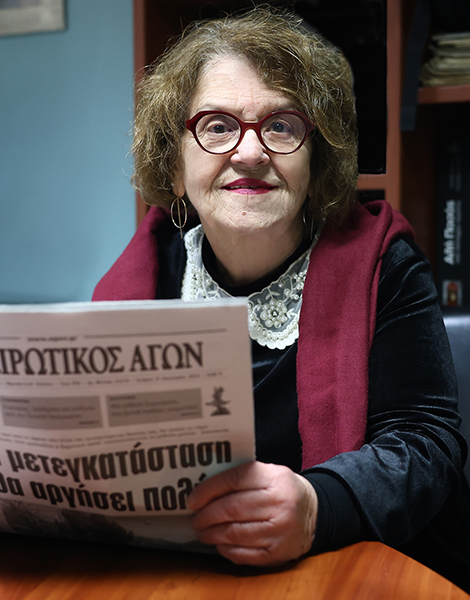

Following Elisaf’s initiative, Romaniotes from around the globe gather [in Ioannina] for the Yom Kippur celebration. “Only upon his passing did everyone realize his greatness,” says Loukia Tzalla, editor of the historic Ioannina newspaper Ipirotikos Agon, as the publication commemorates a century of existence this year. “The mayor represented a break from cultural isolation. He left behind a profound legacy of selfless devotion to the common good, a legacy that must endure, as we are currently experiencing the most promising phase in decades. Our small town is growing and requires forward-thinking leadership. This is a time of significant opportunities. Will they be recognized by all?”

© Nikos Kokkalias

The ‘grades’ of students

Until the opening of key road connections, the only outsiders infusing vitality and funds into Ioannina were students. In 1964, departments affiliated with the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki were established, and six years later, the University of Ioannina was founded, steadily expanding. Today, it stands as the most robust university town in Greece in terms of the resident-to-student ratio.

We met members of the student ensemble “6.5 Grades.” Originating from various parts of Greece, except for the vocalist who hails from Ioannina, they came together through the active association (Musical Society of the University of Ioannina), bonding over tsipouro, hence the name with the alcohol levels. Aspiring computer scientists, chemists, physicists, biologists and doctors, they form a delightful group, all declaring their love for the city, which they describe as having a perfect balance: “neither as vast as Athens and Thessaloniki, nor too small to confine you, surrounded by stunning nature that beckons exploration,” says drummer Vangelis, who is from Kozani.

“The problem is that we love the city as a landscape, but the locals are inherently reserved. You only interact with them as customers at their shops or as tenants. Younger Ioanniniotes are only connected to relatives and old friends. They don’t function as a bridge,” observes saxophonist Giorgos Terzidis, a native of Katerini. “I think because we pass through the city by the thousands for our studies, they don’t see us mentally as a long-term investment, as future residents, and that’s a pity because many graduates would like to live here. Only technology companies that have recently emerged have correctly perceived this need and – by offering job positions – retain some of us,” notes pianist Giorgos Manakos, originally from Trikala. All these make the sole Ioanniniote of the group, Paraskevi, sweetly apologize. She says that the mountains and isolation made Epirotes family-oriented, with a huge love for their homeland, a pride that exists nowhere else. But do the mountains bear the blame?

“Most definitely. But matriarchy is also to blame,” says surprisingly Martha Papadopoulou, head of the General State Archives in Epirus, at a historic mansion in Its Kale, formerly the palace of Ali Pasha and now the headquarters of the General State Archives. “Epirotes and Ioanniniotes always had commercial relations and networking with the Balkans, the West and the City. Men traveled, while women stayed behind to manage household affairs. Their outward orientation did not penetrate the family nucleus.”

Attorney Niki Lappa, from a highly esteemed lineage, added another reason why the university and students did not integrate into the city’s life: “Old bourgeois Ioanniniotes were much more cosmopolitan, experientially trained to coexist with Jews and Ottomans, with foreigners. However, urbanization brought thousands of people here from nearby villages, altering the human geography with the majority adopting a more conservative mindset. Introversion prevailed. University professors also remained confined within their competitive, academic microcosm.”

This article was previously published in ekathimerini.com.