The Panathenaic Way: Athens’ Historic Pathway Comes Alive...

A major restoration project is bringing...

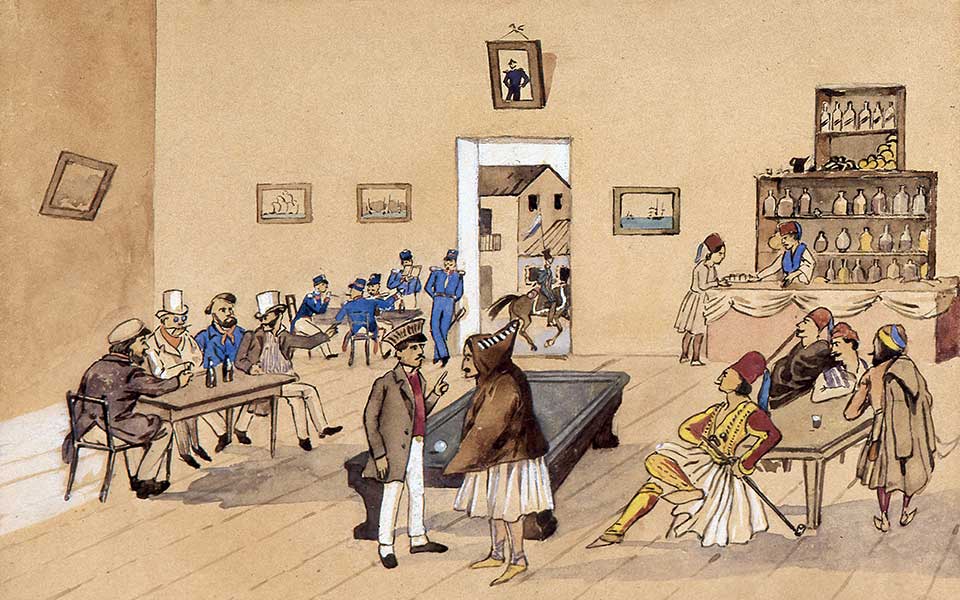

Interest in politics was not limited to the rich or politically ambitious, as most Greeks had a healthy appetite for debate. This Athens kafeneio, like many during Ottoman times, was a stage for political controversy. Watercolor on paper by Ludwig Köllnberger, 1836 (copy).

© National Historical museum/Ministry of Culture & Sports

François-René de Chateaubriand had great confidence in his literary abilities – and consequently in his imagination. While standing on a hill overlooking the Evrota River valley, the author of “Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem” saw a few white stones among the olive trees in the distance and decided they must mark the tomb of King Leonidas. He mounted his horse and rode at a gallop in that direction, shouting “Leonidas! Leonidas!” and waiting in vain for a response. Chateaubriand visited Greece at the beginning of the 19th century, when Athens was still a small village, the Acropolis surrounded by pastureland, and he hurried through. Greece disappointed him, just as it always disappoints its admirers, those who dream of its charms before they see its reality.

That’s how the romantics were: forever in love, forever disappointed by what they saw before their eyes. Before leaving Paris, Chateaubriand arranged to meet Comtesse de Noailles somewhere in Spain. He promised to have completed the chronicle of his Mediterranean tour by then. He traveled through Asia Minor, Palestine, Egypt, Tunisia and Spain, but he devoted a few of the most beautiful pages in all of world literature to his description of the Acropolis. I’ll offer one observation as an example: he never saw the marbles as white. Rather, Chateaubriand saw columns coated with the patina of time, and saw, too, how the light played on them, transforming their color to rose, orange or yellow, depending on the time of day. But never white. It is as if he was providing a counterpoint to Johann Winckelmann, whose theory concerning “white Greece” shaped educated Europeans’ views towards a country emerging slowly from so many centuries of deep slumber and silence.

When Chateaubriand visited Greece, Lord Elgin had already come and gone. The journey to the southernmost tip of the Balkan peninsula required not only daring and a strong constitution, but cultural awareness. Greece was a part of his civilization, yet one that remained under Ottoman rule. As is well known, when the revolution broke out in 1821, Chateaubriand championed the Greeks, along with Delacroix and Hugo, who had never visited its lands.

The Greece that Edmond François Valentin About visited later, in 1852, had already been recognized as an independent state, or rather a “statelet,” still under the rule of King Otto and the Bavarians. It had lost the romantic virginity it held for all those who came before – Chateaubriand, Edgar Quinet and Alphonse de Lamartine, to speak only of the French. Of course, there was also the great figure of Lord Byron, who died in Messolongi. Every March 25th, schoolchildren of my generation saw the portrait of Byron dressed in Greek style in colorful engravings when we celebrated the heroes of the Revolution. Our teachers, not wanting to tarnish his aura of heroism, neglected to mention that he died of illness.

Bandits with a gang of Arvanites, 1870.

© From the book "Athens 1839-1900. A photographic record" of Benaki Museum, private collection.

When About visited Greece, this was already history. The French Archaeological School, the oldest of all such institutions, was already operating in Athens. About was a journalist and novelist who came in the company of some archaeologist friends. He was also a republican, and he had left a France where Napoleon III had abolished the Second Republic. He came to a Greece which, on the one hand, had been integrated into the status quo of the age, fashioned as a nation-state, yet which also maintained its right to paradox. The greatest endowment bestowed upon us through About’s insightful way of seeing the world is in his description of a Greece seemingly destined to remain the paradox that it always was.

About wrote two books featuring Greece. One bore the title “La Grece contemporaine” (Contemporary Greece), and chronicled his travels and memories from the two years he lived in this young nation with an ancient history. It has been recently republished, under the title “Otto’s Greece.” The second is a novel, “Le Roi des Montagnes” (The King of the Mountains). It is a pleasurable narrative that has as much to tell a contemporary reader about the Greece of that era as hundreds of pages of historical research could.

About was a journalist in an age when anyone who wrote for a newspaper or periodical or spoke publicly possessed a necessary erudition, something which is no longer required. He had an extensive knowledge of Greece and of Greek civilization. Before his arrival, he wrote that he “dreamed” of Greece during the hours he spent in the library studying Greek. To him, then, contemporary Greece may have been a political, economic, and social reality, but it hadn’t lost that dreamlike quality. His classical studies helped preserve that veneer.

The geography of the region helped as well. Crossing the Mediterranean from Toulon or Marseilles to Piraeus remained a quasi-adventure. The journey overland through Italy may have saved the trouble of seasickness, but was time-consuming and demanded the continual display of travel documents, with all that entailed. The Ottoman Balkans were best avoided. The traveler had every right to feel like the hero of a noteworthy adventure – a fact that obliged him to keep his eyes open and his wits about him.

The narrator of “The King of the Mountains” is a young German botanist, who comes to Athens to collect material which he hopes will further his career and supplement his meager income. The protagonist is the “king” himself, the brigand Hadgi-Stavros, whose men control the Attica peninsula in an age when the Greek state claims to have banished brigandry from its lands. “Brigandry” captures the activities of revolutionary irregulars who, after independence, were unable to find a place in the civil sphere, or who thought that continuing their exploits would prove more profitable than whatever position was offered them by the new independent Greek state.

Athenian ladies dressed in costumes designed by Queen Amalia join in Greek dances.

© Benaki Museums archives.

We shouldn’t forget that the first revolutionaries in Greek lands were the “klephts.” These groups of bandits were well-versed in guerrilla warfare and showed extraordinary endurance in the face of the hardships they suffered. They robbed both Ottomans and their fellow Greeks. After the revolution, they preferred to risk their lives rather than pay taxes to the newly-formed state.

Some of the most prominent klephts had previously been drafted by the Ottomans to manage relations with the local population. Klephts who had been taken in by the administration of that era were known as “armatoli” and, together, they would tame any resistance and manage the public coffers. They controlled entire regions and ensured public peace, as well as the economics of Ottoman rule. But they had also learned the art of war, which is why they proved useful to the Greeks during the uprising after 1821. As for the role of brigandry in the history of the Greek people, please don’t be shocked. It is an ancient story. All one needs to read to confirm this is Thucydides’ introduction to his “History of the Peloponnesian War.”

For anyone with experience of life in contemporary Greece, it will suffice to retain two fundamental points from this story. The first is the people’s relationship to the state. If the state can’t find a place in society for a particular individual, that person feels betrayed and has no reason whatsoever to respect the state or obey its rules. The second point, which arises from the first, regards the individual’s relationship to taxation. From the moment that the state has betrayed you, you have no reason to pay it.

The consistency of Greek society on this point is remarkable. In the mid-19th century, when About visited the nation, the problem was who would be given positions in the state apparatus and who would pay taxes. In 2018, the world has changed, the words we use are different, but the fundamental points remain the same. As About says – I can quote him by heart – “Greeks identify freedom with disobedience before the law.” How clearly he saw into our collective character, even though he only lived among us for two years. And how impressive it is that much of what he saw in 1852 still applies today.

Traditional Attica dress, 1855.

© Philippos Margaritis, National Library/from the book "Athens 1839-1900. A photographic record" of Benaki Museum.

General Christodoulos Hadjipetros, 1855.

© Philippos Margaritis, National Library/from the book "Athens 1839-1900. A photographic record" of Benaki Museum.

The novel “The King of the Mountains” is about a brigand who has set up shop somewhere in Hasia, to whom others bring their loot. His men abduct the German botanist and an English lady with her daughter, all of whom believed assurances made to them that brigandry had been banished from the land. The “king” welcomes them with the graciousness suited to his position, makes sure they want for nothing, and lays out his business plans. The “king” works with a bank in London, where the hostages’ friends must deposit their ransom. What could be simpler than that? A business deal like any other. But the botanist tricks him, saying that he will have to provide a receipt for the sums deposited – thereby admitting his guilt – and the brigand, thinking this entirely normal, accepts.

The end of the novel conveys, in the strongest way possible, the physiognomy of a Greece teetering on the edge of schizophrenia. On the one hand, an official state that upholds – most of the time – the rules of the status quo, and on the other hand, a society that follows its own rules and conforms to its own status quo. The two parts coexist: the unfortunate German botanist meets Hadgi-Stavros at a fancy ball. The brigand king is there because he has ambitions to obtain a ministry, perhaps even become secretary of justice. Consider, if you will, the paradox involved in that. (It reminds me of Don Corleone’s hope in “The Godfather” that his son might one day become a senator.)

For many generations of Greeks, “The King of the Mountains” was required reading. It was even more widely read than About’s travel memoir – perhaps because it partook in the freedom of novelistic writing, which doesn’t require the reader to believe in the reality of what it describes. In “Otto’s Greece,” About attempted a portrait of the country that was not at all flattering, especially to those who felt a mirror was being held up to them as they read. Attacks can be borne, but it is difficult to bear a penetrating gaze which strips you down. About described the reality he saw before him with sincere interest in, and sympathy for, the people, but he was full of candor and a willingness to deliver unflinching judgments.

About’s critiques range from the simple to the complex. He doesn’t find Greek women beautiful, or, at least, as he had imagined them. What is to be done about that? He wasn’t, to be sure, an idiot; he wasn’t expecting that in the Athens of the 1850s he’d find himself on the Champs-Elysées or the other grand boulevards of Paris, but he did observe that he met with so many lawyers and doctors that he began to wonder how many courts and how many patients would be required – not just in this small country, but in the entire region – in order to keep them all in business.

Of course, he couldn’t know that Greece, approximately two hundred years later, would continue to create laws to keep its lawyers in business. As we’ve learned, Greek society may have many faults, but it also has a steady set of values. It continues to produce doctors and lawyers, and to create the proper conditions to maintain them. How would they survive without the country’s amazing, prehistoric structure of bureaucracy?

Athenians visiting the Acropolis, 1868.

© From the book "Athens 1839-1900. A photographic record" of Benaki Museum, private collection.

About did not expect that a statelet born of debt from the guts of the Ottoman Empire just a few decades earlier would have the same infrastructure as Europe during the industrial revolution. He describes a businessman he met who wanted to take part in the Paris Industrial Exposition, exhibiting olives and raisins. These were honorable goods from Greek soil, but irrelevant to the industrial revolution that had already begun to break out in the rest of Europe. (Let us not show contempt for this businessman – just as About did not show him contempt.)

The businessman was looking toward Europe, as did all the dynamic elements of 19th century Greek society. He simply didn’t suspect that the distance between himself and his destination was quite so great. He thought he could take off his traditional fustanella and don a pair of trousers, as he thought industry was an activity like the harvesting of olives. He wanted to become like the other Europeans he admired, but didn’t have the means to understand either their language or their way of life. Here we see – in strong relief – the “Greek paradox” that About encountered.

The Greeks were a peaceful, mostly sober people who wanted to be integrated into the history of the European world. They didn’t, however, want to cede even an inch on their beliefs or way of life. In a village in Messinia, if I’m not mistaken, where silk was produced, About tried to show them how silk was made in France, which took far less time. He described their enthusiasm: for two days and nights, the village spoke of nothing else. Grandsons called their grandfathers, fathers called their sons, and so on and so forth, to hear what the Frenchman had to say. On the third day, they continued their labors in their accustomed fashion. They were curious – but that’s as far as they went.

About presents the Greeks as curious and peace-loving; so peace-loving that, in the battles of the Revolution, they put the philhellenes on the front lines, while they pushed from behind. Observations like this might seem “unseemly” to About’s Greek reader, but they’re the very foundation of our collective consciousness. Foreigners on the front line, us behind. At the end of the day, I don’t know if there’s an equivalent to the word “philhellene” for any other European nation. But philhellenism was one of the factors that shaped the fate of contemporary Greece, making the country believe it was unique. Greece: the beloved paradox of European civilization.

The Tower of the Winds, 1853-54.

© James Robertson, Christos Kalemkeris Photo Museum/from the book "Athens 1839-1900. A photographic record" of Benaki Museum.

The Greeks’ love of equality doesn’t allow them to accept anyone or anything that stands apart. This is perhaps the French traveler’s most timely observation about the Greek collective consciousness. The lovable paradox abhors anything exceptional, including excellence, and defines freedom as freedom from law; its prime interest is to maintain its own state of paradoxicality.

There were other travelers, too, more famous than About. In addition to Chateaubriand, there was Ernest Renan (with his incredible “Prayer on the Acropolis”) and even Charles Maurras. Maurras came to Greece in 1896 as a reporter to cover the first modern Olympic Games, and adopted the modern Greek narrative, which presented the marathon champion Spyros Louis as the direct descendent of the ancient Greeks. Of course, Maurras had his own narrative of “Greco-Roman civilization” in mind, a theory that anointed him the spiritual father of the French far right. He died seven years after the end of World War II, shortly after his release from prison, having been convicted of collaborating with the Germans. These men weren’t like About, you’ll say – and yet all were characteristic examples of the manner in which the French travelers saw this small country in the southern Balkans: either with Chateaubriand’s romanticism, About’s realism, or Maurras’s idealism, but always with an interest and curiosity that, in the end, acted to fortify the coexistence of the Greek paradox with the European status quo.

Returning to Paris after his Greek adventure, Edmond About became the publisher of a newspaper that opposed the regime of Napoleon III. He was given an academic position but died before he could assume it. His fame as a writer in his home country was crushed between the massive stones that supported the acknowledged canon of 19th-century French literature. In Greece, his books were read and forgotten, probably because they didn’t meet the demands of a narcissistic readership. Then, in 2018, the Greek reissue of “Otto’s Greece” met with unexpected success. This is one of the positive results of the crisis: certain steps are being taken toward self-awareness and deliverance from the weight of collective narcissism. It would seem that a large part of Greek society now understands that the gaze of an outsider often discerns more truth than the mirror affords.

A major restoration project is bringing...

As its historic estates fade and...

A forgotten world comes to life...

Cultural leaders reflect on Thessaloniki’s layers...