The sea was calm that fateful day, a deceptive tranquility that belied the peril lurking beneath the waves. Onboard the SS Arcadian, a troopship carrying soldiers across the Aegean Sea, there was a mixture of weariness and anticipation. The men, packed into the vessel’s hull, were likely exchanging stories, perhaps laughing to ease their nerves, or writing letters to loved ones back home. The salty breeze mingled with the scent of oil and machinery, a reminder of the ship’s mechanical heart driving them forward through uncertain waters.

Suddenly, a deafening explosion shattered the calm. The ship lurched violently as a torpedo from the German U-boat UC-74 struck its hull. Chaos erupted; men scrambled to their feet, disoriented and terrified. As the Arcadian began to list, water poured in, and the realization of their dire situation set in. Within minutes, the vessel that had once been a lifeline became a death trap. For 279 of the 1,335 troops and crew onboard, the Aegean Sea would become their final resting place.

Fast forward 107 years, and a team of Greek commercial divers and researchers led by Kostas Thoktaridis has brought the SS Arcadian back into the light. Using advanced sonar and remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) to locate the site, they were greeted by the haunting silhouette of the once-majestic ship, now a ghostly presence on the seabed. Their remarkable discovery, at a depth of 163 meters southeast of Sifnos, has reignited interest in the vessel’s tragic story, serving as a poignant reminder of the lives lost during World War I.

© Public domain

Repurposed for War

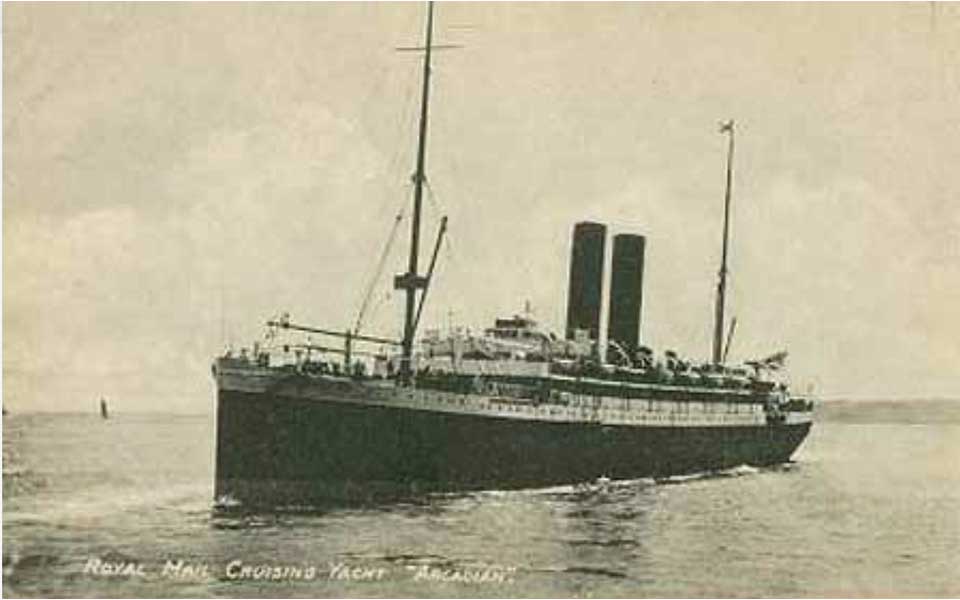

The SS Arcadian was originally built as a transoceanic liner, intended for the transport of passengers on the Great Britain-to-Australia route. Constructed by Vickers, Sons & Maxim Ltd. in Barrow-in-Furness, England, the vessel launched in 1899 under the name SS Ortona. It served the Orient Steam Navigation Company, embarking on its maiden voyage on November 24, 1899, prior to being used to return British and Commonwealth troops after the end of the Second Boer War (1899-1902) in Southern Africa. Refitted as a 320-person cruise ship in 1910, two years before the completion of the infamous RMS Titanic in April 1912, the Arcadian was the largest dedicated cruise ship in the world.

With the outbreak of World War I, the demands of the war effort transformed many such vessels. The SS Ortona, rechristened the SS Arcadian in 1910, was no exception. Requisitioned by the British Admiralty in February 1915 and given the prefix “HMT” (Hired Military Transport), it was repurposed as a troopship during the opening phase of the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign (1915-1916). Its new role was far from the leisurely ocean voyages it had once known. Instead, it now carried troops, bound for the battlefields of the Dardanelles and the Middle East, its decks and cabins filled with young soldiers of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force.

Repurposed for war, the SS Arcadian played a crucial role, transporting thousands of men to and from the front lines, and briefly serving as a headquarters ship for campaign commander, General Sir Ian Hamilton. However, this transformation also marked it as a target for enemy submarines prowling the waters of the eastern Mediterranean, ever vigilant for opportunities to disrupt Allied supply lines and troop movements.

© Public domain

Torpedoed in the Aegean

On April 15, 1917, the SS Arcadian was on a routine voyage through the Aegean Sea. It was carrying soldiers from Salonika (Thessaloniki) to Alexandria in Egypt, a journey fraught with danger as German U-boats patrolled the region. Despite the risks, such voyages had become a grim necessity in the war effort.

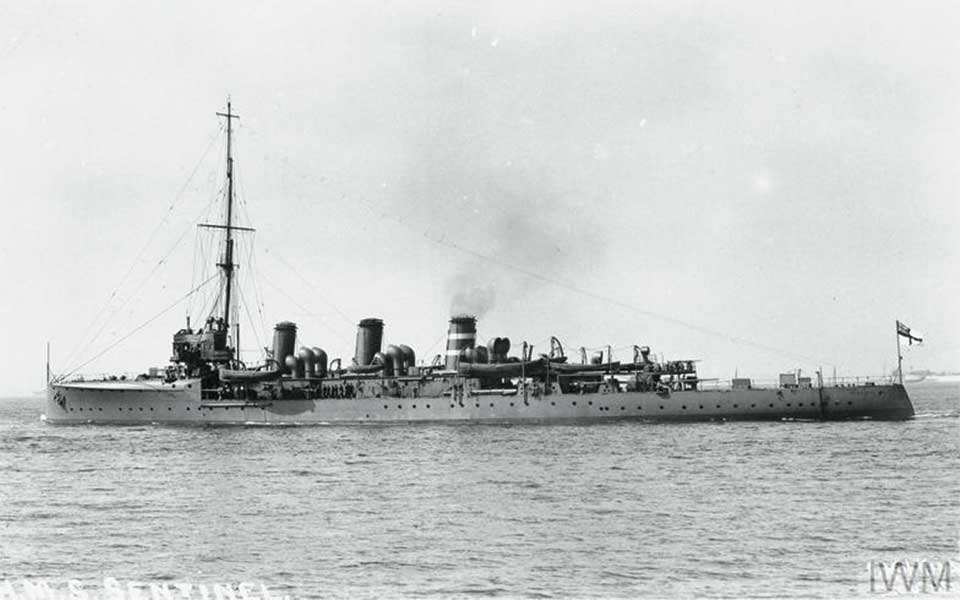

The attack came without warning, some 42 km northeast of the Cycladic island of Milos. German U-boat UC-74, commanded by Oberleutnant zur See Wilhelm Marschall, had been lurking in the area, searching for enemy shipping. Despite irregular course changes (“zigzagging”) to deter submarine attack, and escorted by the scout cruiser HMS Sentinel, the slow-moving Arcadian, with its precious human cargo, presented a tempting and vulnerable target. At 5:44 pm, the torpedo struck with devastating precision, hitting the ship’s engine room and causing an immediate, catastrophic explosion.

Panic spread quickly among the troops onboard. The blast had caused significant damage, and the ship began to sink rapidly. Lifeboats were launched in a desperate bid to save as many lives as possible, but the chaos and confusion made an orderly evacuation practically impossible. In the ensuing six and a half minutes, 279 lives were lost as the SS Arcadian disappeared beneath the waves, including renowned French-born British bacteriologist Sir Marc Armand Ruffer, the father of modern palaeopathology. Remarkably, four of the ship’s lifeboats were successfully lowered during the attack. A subsequent enquiry by the Admiralty concluded that many more souls would have been lost had it not been for the exemplary discipline of the troops and crew and the regular lifeboat drills carried out in the days prior to the sinking.

Survivors later recounted the horror of that day. Men struggled to stay afloat in the churning waters, clinging to debris and praying for rescue. For those who managed to survive the initial sinking, the ordeal was far from over. The threat of hypothermia, exhaustion, and further attacks from UC-74, still lurking nearby, loomed large. Some of the survivors were picked up by HMS Sentinel while others were picked up by French warships sent from Milos. The remainder were retrieved close to midnight by the Q-ship HMS Redbreast, after spending nearly five hours afloat in the Aegean.

© Public domain

The Unsinkable Thomas Threlfall and Captain Willats

Among the survivors of the SS Arcadian was crewman Thomas Threlfall, a man whose life seemed marked by prolific maritime disasters. Remarkably, Threlfall had also survived the sinking of the RMS Titanic five years earlier to the day, on April 15, 1912. His survival of two of the most infamous shipwrecks in history is a testament to both his resilience and the capricious nature of fate.

Threlfall’s experiences must have been harrowing. Surviving the Titanic’s icy demise in the North Atlantic only to face death again in the warmer waters of the Aegean left an indelible mark. He later stated: “It was the same day of the week, and the same date of the month that the Titanic went down…and I have come safely out of both affairs.”

When asked which of the two sinkings was worse, he stated:

“Well, the Titanic stopped afloat for a couple of hours, and we had time to turn around, but of course you could not live in the water that night. This time we had calm sea and warm weather, and you had a chance, but with the Titanic you died in the water almost as soon as you got in.”

His remarkable story is a poignant reminder of the human capacity to endure, even in the face of unimaginable adversity.

Equally compelling is the story of Captain Charles L. Willats, the steadfast commander of the SS Arcadian. In his 23 years with the Royal Mail Line, Captain Willats had already faced the perils of the sea multiple times. On November 5, 1915, as captain of the ocean liner Pembrokeshire, he ran aground on a reef in the Canary Islands. Less than two years later, on January 7, 1917, while aboard the cargo ship Radnorshire in the South Atlantic, his vessel was sunk by the German auxiliary cruiser Moewe. Captain Willats and his crew were captured and held until they were disembarked in Brazil. They then boarded the troop ship Drina to return to England, only for the Drina to be sunk by the German submarine UC-65 near the British coast on March 1. Despite these harrowing experiences, Captain Willats survived all three shipwrecks.

Rediscovery

The recent discovery of the SS Arcadian’s well-preserved wreck southeast of Sifnos island has brought this forgotten chapter of history back into the public eye. Led by Kostas Thoktaridis, a renowned Greek diver and explorer, the research team embarked on an ambitious mission to locate the ship. Their success, at a depth of 163 meters, marks a significant achievement.

Thoktaridis and his team faced numerous challenges in their quest. The depth of the wreckage, coupled with the strong underwater currents of the Aegean, made the search both physically demanding and technically complex. Advanced sonar technology and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) played crucial roles in locating and documenting the wreck.

“The quality of the metallic alloys used in the shipbuilding of the Arcadian is a major factor in the preservation of the wreck up to this day,” Thoktaridis told the Athens Macedonia News Agency (AMNA).

“It appears that the bow of the Arcadian initially landed on the bottom of the Aegean, with the result that the deformations of the plates are visible. Due to the length of the ship (152.4m) and the depth of the sea area, which is only 163 meters, since the bow crashed first while the stern was still sinking, this helped the wreckage to stay aligned and upright till today,” he added.

The rediscovery of the SS Arcadian is more than just a remarkable archaeological achievement; it is a poignant reminder of the human cost of war, underscoring the sacrifices made by so many during World War I. The ship’s tragic sinking on April 15, 1917, coupled with the tales of survival like those of Thomas Threlfall and Captain Willats, weaves a narrative that is both heart-wrenching and inspiring.

In the depths of the Aegean, the wreck of the Arcadian rests as a silent witness to the tragedies of war and the resilience of the human spirit. By carefully exploring and preserving these underwater time capsules for future generations, we not only honor the memories of those who perished but also enrich our understanding of history, ensuring that the echoes of the past are never forgotten.

With information in Greek from kathimerini.gr.