Easter in the Mystical Castle of Monemvasia

In the castle town of Monemvasia,...

Portrait Charles Robert Cockerell, by Christian Albrecht Jensen, 1838.

This is part of a new series of articles by Greece Is on the adventures of early travelers to Greece, including as much as possible the travelers’ own words recorded in diaries and letters.

First off, we will hear from Charles Cockerell who visited Greece in the early years of the 19th century as a budding young English architect, and antiquities looter.

Background

Today in Britain, Charles Cockerell (1788-1863) is remembered as an illustrious architect who designed numerous well-known Greek Revival (late Neoclassical) monuments around the country, including the Edinburgh National Monument (1824-29); the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford (1841-45); several Bank of England branches in Bristol, Manchester and Liverpool (1844-48); and the interiors of the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge (1948) and St. George’s Hall in Liverpool (1951-54).

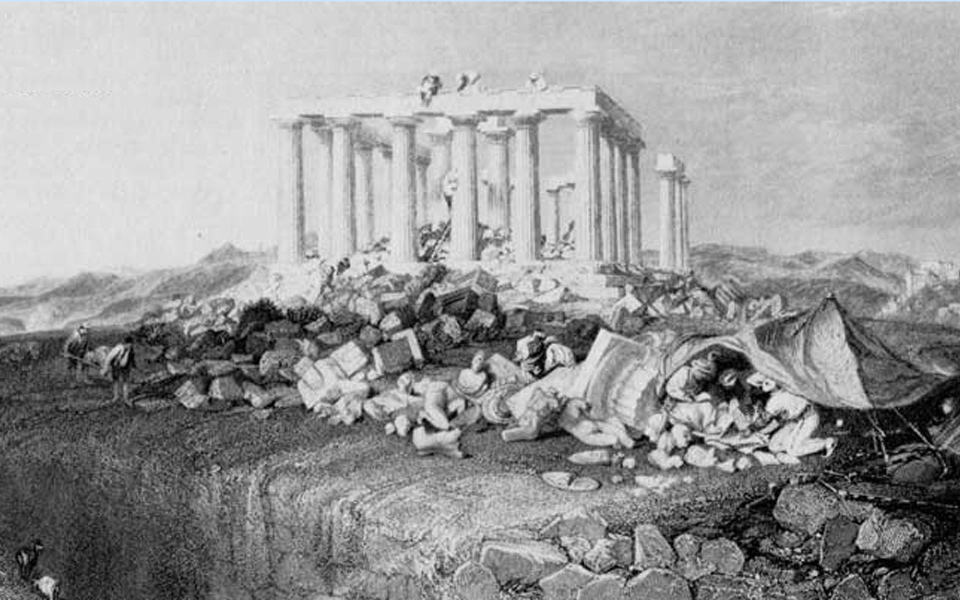

In Greece, however, Cockerell has a different reputation. He is most often recalled as one of the early antiquarian visitors from the West, a student of ancient architecture and a looter of Greek antiquities, especially on Aigina Island and at Bassae in the Peloponnese.

Like many young European aristocrats of his time, he viewed travel as part of his education and departed on a seven-year “Grand Tour” to the East in 1810, where he lingered the longest in Greece. To give his journey an official air and to offer him some protection, his father pulled strings to have him appointed a King’s Messenger, entrusted with official dispatches to be delivered to the British Navy’s fleets in Cadiz, Malta and Constantinople.

The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, designed by CR Cockerell

© Shutterstock

Cockerell, in one of his own letters home concerning the Ottoman-ruled East, writes:

“I ought to give you a notion of the political state of this part of the country. Ali Pasha of Yanina [Ioannina] rules over the Morea [Peloponnese], Albania, and Thessaly nearly up to Salonica [Thessaloniki], while the Pasha of Serres has Salonica and Macedonia nearly up to Constantinople; and both are practically independent of the [Ottoman] Porte, obeying it or assisting it only as far as they please. Now, Ali Pasha has sent his son Veli with 15,000 men to join the Sultan’s army against the Russians, but on his way has encamped near Salonica and threatens to take possession of it…

“Meanwhile, the Sultan has given another pasha a firman to take the Morea in Veli Pasha’s absence, and he (Veli) is now waiting for his father Ali’s advice as to whether he should proceed to the war, recover the Morea, or take Salonica. Fancy, what a state for a country to be in! The Sultan is a puppet in the hands of the janissaries, who on their side are powerless outside [Constantinople], so that the country without and within is in a state of anarchy.”

The Edinburgh National Monument, designed by CR Cockerell and W.H. Playfair.

© Shutterstock

Arrival in Greek Lands

On reaching the Ottoman capital, Cockerell met and befriended a young fellow Englishman John Foster (architecture student, Liverpool), with whom he would continue his travels and later share accommodations in Athens. In mid-September 1810, the pair left Constantinople for Greece, pausing en route at ancient Troy, where Cockerell, inspired by Homeric Achilles, stripped naked and ran three times around the supposed tomb of Patroclus.

From Thessaloniki, they booked passage for Athens, initially on a Greek merchantman, stopping along the way at Skyros, Andros, Tinos, “Great Delos” (Rineia), Delos, Mykonos and Syros.

Modern-day Andros

© Shutterstock

Pirates and Mutineers

Sea travel at the time was common but risky. Near “Scopolo” island [Skopelos], Cockerell relates, “a boat came out and fired a gun for us to heave to. The crew told me she was a pirate, but when we fired a gun in return to show that we were also armed, the crew of the boat merely wished us a happy journey.”

Later, “the wind falling light, we anchored in a small bay and landed, and there we made fire in a cave and cooked our dinner. It was most romantic.”

More trouble ensued in Andros:

“While our ship was lying in the port, our sailors became mutinous. They began by stealing a pig from the land, and then went on to ransack our baggage and steal from it knives, clothes, and other things. All this happened while we ourselves were on shore, but our servants remonstrated, whereupon the scoundrels threatened to throw them overboard. There was nothing for us to do but apply to the English consul for protection. He sent for the chief instigator of the troubles, but, as soon as he got ashore, he ran away and was lost sight of.”

In the end, Cockerell and his fellow foreign travelers left the ship and shifted their goods to a smaller vessel to continue their journey.

View of Delos

© Shutterstock

Exploring Delos

“From Tinos we sailed across to Great Delos, slept in a hut, and next day went on to Little Delos. Here there was nothing to sleep in but the sail of the boat, and nothing to eat at all. Everything on the island had been bought up by an English frigate a few days before. We were obliged to send across to Great Delos for a kid, which was killed and roasted by us in the Temple of Apollo. I spent my time sketching and measuring everything I could see in the way of architectural remains, and copying every inscription. I had to work hard, but without house or food we could not stop where we were, and in the evening we sailed to Mycone [Mykonos].”

“Next day, I went back to Delos, and after much consideration resolved to try to dig there. I had to sleep in the open air, for the company of the diggers in the hut was too much for me. First I made out the columns of the temple and drew a restoration of the plan. Then we went on digging, but discovered next to nothing – a beautiful fragment of a hand, a dial, some glass, copper, lead, etc, and vast masses of marble chips, as though it had once been a marble mason’s shop. At last it seemed to promise so little that I gave it up and went back to Mycone; but on the 28th [possibly of November], not liking to be beaten, I went back alone to have a last look. But I could discover no indications to make further digging hopeful, so I came away.”

Portrait of a young Charles Robert Cockerell by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, 1817.

Athens, New Friends

Finally arriving in Attica in early December 1810, Cockerell spent his first few days at Zea port and Piraeus exploring and sketching. There were no hotels in Athens; only rented rooms, such as those Lord Byron, another recent visitor from the West, had hired, or, for longer stays, entire houses. Cockerell and Foster chose this latter option, deciding to reside together and share their expenses.

While in Athens, Cockerell met a number of other youthful travelers with similar interests. In addition to Foster, his new circle of friends included Otto Magnus von Stackelberg (painter, archaeologist) from Estonia; Jakob Linckh (painter, archaeologist) from Cannstatt/Stuttgart; and Peter Oluf Brøndsted (archaeologist) and Georg Koës (philologist) from Denmark.

Cockerell also befriended Baron Carl Haller von Hallerstein (architect, archaeologist, art historian) from Bavaria, as well as Louis-François-Sebastien Fauvel, the well-known French consul in Athens, a painter, archaeologist and voracious collector of antiquities. Occasional acquaintances further included the Neapolitan painter, Lusieri, the draughtsman to Lord Elgin, who had infamously made off with the Parthenon’s sculptures, the last five crates of which left Piraeus in April 1811 some four months after Cockerell’s arrival.

Drawing of the temple of Aphaia on Aigina island, by Charles Robert Cockerell, 1811

Bound for Aigina

Cockerell and his friends planned to tour the Morea, “but before doing so, we determined to see the remains of the temple at Aegina, opposite Athens, a three hours’ sail. Our party was to be Haller, Linckh, Foster, and myself.”

After being delayed several hours by “a smouldering war between our servants and our janissary,” Cockerell describes an encounter with Byron himself:

“…we did not walk down to the Piraeus till night. As we were sailing out of the port in our open boat, we overtook the ship with Lord Byron on board. Passing under her stern, we sang a favourite song of his, on which he looked out of the windows and invited us in. There we drank a glass of port with him, Colonel Travers, and two of the English officers; and talked of the three English frigates that had attacked five Turkish ones and a sloop of war off Corfu, and had taken and burnt three of them. We did not stay long, but bade them ‘bon voyage’ and slipped over the side. We slept very well in the boat, and next morning we reached Aegina.”

Cockerell and company make extraordinary discoveries in Aigina, clandestinely ship their finds off to Athens and later explore ancient Eleusis.

Travels in Greece, By Charles R. Cockerell, Anagnosis Publications, Athens, 2008. Abridged from Travels in Southern Europe and the Levant, 1810-17: The Journal of C. R. Cockerell RA. First published 1903.

In the castle town of Monemvasia,...

Anyone who has visited Tsintzina, the...

From mountain villages to forest retreats,...

Greece Is presents "Peloponnese Trails," a...