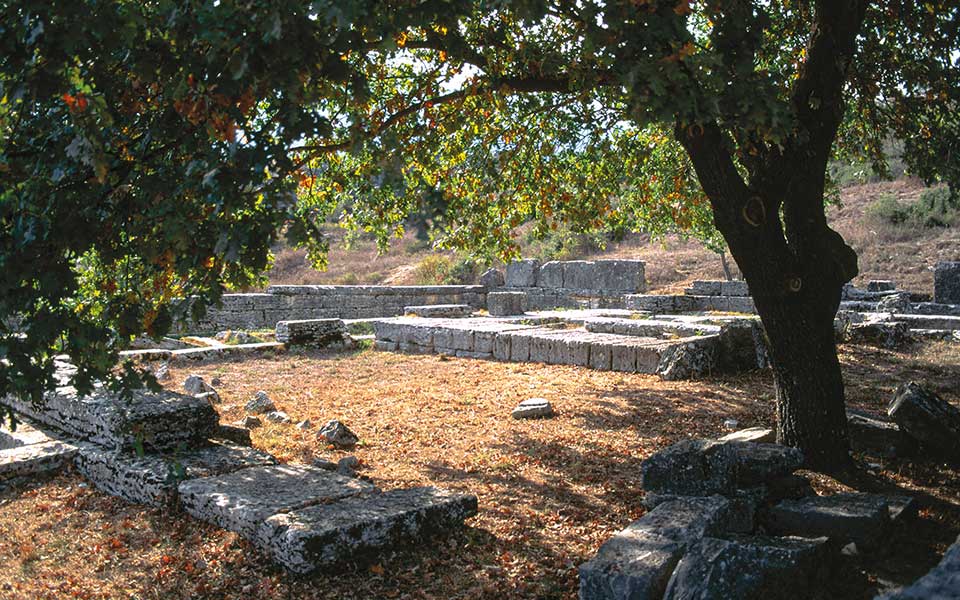

The leaves of the oak tree in the Sacred House of Ancient Dodona still rustle in the wind. The tree was planted by Professor Sotiris Dakaris in the 1950s in an effort to recreate the ancient environment – a reminder of the sacred oak tree that once existed here and gave the first oracle in the history of the ancient world. Other “signs” that revealed the will of Zeus included the murmuring of the waters in the spring, the sound of bronze cauldrons on tripods and of bronze vessels hanging from the branches, and the flying of birds.

Located 20km away from Ioannina, the Sanctuary of Dodona was active from the Bronze Age, with evidence of worship of the goddess Gaia (Earth), until possibly the 4th century AD, when the emperor Theodosius prohibited all forms of pagan worship. Excavations have yielded unique information about ancient worship, as a total of 4,216 inscriptions have been found, which may even shed light on the evolution of the language used among the common people.

Archaeologist Dr. Barbara Papadopoulou, director of the Arta Ephorate of Antiquities and deputy director of the Ioannina Ephorate of Antiquities, answers our questions and shares the secrets of the oracle of Dodona.

Why is the oracle of Dodona considered the most important in ancient Greece?

It was certainly “the oldest of the oracles in Greece,” as attested by Herodotus, and it was widely known during the Homeric era, as evidenced by references in the epics. The hero Achilles addresses his invocation for his friend Patroclus to Dodonian Zeus, while Odysseus, during his ten-year sojourn, visits the oracle of Dodona to inquire about his return to his homeland. Furthermore, it is notable for serving as a center of power, the focal point of economic and political activity on the mainland, as well as a religious center with significant geographical reach, even into Late Antiquity.

Its architectural composition reflects its multifaceted and complex role. The Sacred House with the oak tree serves as the central nucleus around which the public (Prytaneum), political (Bouleuterion – Council Chamber), cultural (Theater, Stadium), secular (Colonnades), and religious-worship structures (temples) of the Sanctuary of Dodona were constructed.

How did the oak tree acquire such “power”?

It was believed that Zeus and Dione dwelt in its roots. The rustling of its leaves and the murmur of water at its roots from the Naiad’s spring were interpreted as prophetic signs.

At the end of the 8th century BC, the sounds produced by striking bronze cauldrons on tripods surrounding the oak tree were believed to ward off evil and constituted a form of divination (known as “Dodonaean bronze”). The same was true of the Corfu scourge (or whip) offered by the people of Corfu in the late 4th century BC, which consisted of two columns supporting a bronze statue of a child, a triple bronze scourge, and a bronze cauldron. As the scourge swayed in the wind, it struck the cauldron, and the sound was interpreted as an oracle. Cicero mentions the method of casting lots, which is supported by the discovery of lead votive tablets bearing the inscription “concerning the lot.”

© Ephorate of Antiquities of Ioannina

What kind of information did the faithful want to know?

The vast majority of the questions were of a private nature, though some of them were of public interest as well. Private questions concerned health, finance, childbearing, work, weather conditions, agricultural matters, and other topics that have worried people throughout history. Public questions concerned matters of worship and religious ceremonies, the buying and selling or liberation of slaves, the outcomes of contests, etc.

What are the most significant findings?

The most important findings are the lead votive tablets on which the faithful wrote their questions. In fact, the process of their inclusion in the UNESCO “Memory of the World” program has already begun. Their value lies in the uniqueness of the primary material; it makes a significant contribution to the study of ancient Greek religion, which suffers from a scarcity of written sources.

Initially, questions were submitted orally. Starting in the 6th century BC, they began to be inscribed on rectangular lead tablets. However, answers continued to be given orally, and only rarely in writing. The main bulk of these votive tablets came to light during the systematic excavations carried out by Dimitrios Evangelidis (1929-1935 and 1952-1959), which were continued after his death by his collaborator Sotiris Dakaris. In the mid-1970s, Dakaris planned the publication of the entire corpus of votive tablets, a total of 4,216 inscriptions, which was published in 2013 in two volumes by the Archaeological Society at Athens.

Why were the priests of Dodona barefoot, and why did they lay on the ground?

The priests and priestesses of the oracle had the duty of interpreting the oracles, and ancient Greek texts make extensive reference to the mantic rituals. According to Homer, the priests did not wash their feet and slept on the ground to be in direct contact with the earth. Not washing their feet and lying on the ground were considered primitive religious practices, like going barefoot, and were associated with the priests’ mantic abilities, which they drew from Mother Earth.

Archaeological Site of Dodona, tel: 26510-82287; open daily except Tuesdays, from 08:00 to 16:00; ticket: 8 euros (or 10 euros for the Unified Ticket for the Archaeological Museum of Ioannina and the Byzantine Museum of Ioannina).

The Story of a Restoration

The ancient theater of Dodona was constructed during the heyday of the Sanctuary, in the early 3rd century BC, when Pyrrhus transformed the outdoor sanctuary into a monumental structure. It is estimated to have had a seating capacity of 15,000-17,000 spectators, and in Roman times it was converted into an arena for gladiatorial combat and duels. The systematic excavations begun in 1920 under the supervision of Professor G. Sotiriadis have continued intermittently until today. The first extensive restorations were carried out in the 1960s and 1970s. However, we noticed significant architectural interventions that changed the site’s characteristics during the new phase of restorations, which started in 2000. Modern techniques were used to correct the mistakes made during the initial interventions, restoring the aesthetics and morphology of the site. The lower zone was fully unveiled to the public in June 2022, and work is still ongoing in the middle zone. Moreover, the ancient theater of Dodona has been added, along with 13 other theaters, to the UNESCO World Heritage Convention Tentative List for Greece.