As we sail between two dots of arid land in the middle of the Aegean, they appear so much more welcoming than their names would suggest: We are between Mikros (Small) and Megalos (Big) Anthropofagos (Man-Eater), two islets that are part of the Fournoi archipelago in the Eastern Aegean. According to local lore, their name derives from the fact that many a ship has been smashed to pieces on their rocky shores. Another story says that a group of sailors who were shipwrecked here without food or water resorted to cannibalism. On a day so clear and calm, it is hard to believe such tales.

We have sailed here with a group of marine archaeologists, who are getting ready to dive down into the waters to explore the world beneath us.

Before they can load the oxygen tanks on their dinghy, they are approached by a fishing boat from Kalymnos.

Its captain jumps in, already wearing his scuba suit. He says he has valuable information. “There’s a shallow just here, in the cove,” he says pointing to a map. He promises the archaeologists that if they dive at this spot, they’re sure to find a shipwreck. “I dove 50 meters for sponges and the amphorae are all whole. You may find as many as 2,000 pieces,” the spongediver says.

“We’re trying to get them on our side because they know where these treasures are located,” adds the head of the ephorate, Angeliki Simosi.

It was an unexpected tip. The team from the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities has been trying to convince the locals to be more forthcoming about anything interesting they may have seen for the past two years.

Testimonies from fishing boat owners, spearfishermen and divers last year proved invaluable, particularly those from locals, and in 10 days of diving, Greek marine archaeologists, with the cooperation of American colleagues from the RPM Nautical Foundation, spotted evidence of 22 wrecks, whose estimated dates range from ancient times to before the 1821 Greek War of Independence. This June, using new information, the same team discovered dozens more, brining their total to over 40.

“We only found a few of the wrecks on our own; most of our discoveries were thanks to information from people who work at sea,” says the ephorate’s director of research at Fournoi, Giorgos Koutsouflakis.

At least 15 people have offered evidence and, by coincidence, the descendant of a pirate has become one of the archaeologists’ most valuable sources of information.

© Vasilis Mentogiannis

Like seashells from the seabed

Manos Mytikas studied civil engineering and works at the Municipality of Fournoi Korseon, but the sea is where he feels happiest. He’s been free diving and exploring the islands’ coasts since he was a boy. “The sight of pottery and broken amphorae is very common in the seas around Fournoi. Many people have amphorae in their homes that they’ve pulled up while fishing, like bringing up seashells,” he says.

Mytikas has the same name as one of his ancestors who is described as a “notorious Procrustes” by historian Emmanouil Kritikidis in his book “Topography of Ancient and Modern Samos,” referring to the mythological bandit whose father was none other than Poseidon himself. According to the writer, the bygone Manos Mytikas would invite fishermen who moored in the island’s harbor into his home and rob and murder them before sinking their boats. He was sentenced to death by sword in 1863.

Decades later, his descendant drew up a map showing the locations of around 30 wrecks he had spotted while spearfishing. His telephone call to the ephorate’s offices a few years ago was catalytic.

“As a public employee you can find all sorts of excuses not to do something. At the time we had funding problems,” says Koutsouflakis. “But the phone call from Mytikas changed our entire mind-set. An expedition seemed possible if we had the support of the locals.”.

© Enri Canaj

“But the phone call from Mytikas changed our entire mind-set. An expedition seemed possible if we had the support of the locals.”

The discussion with American marine archaeologist Peter Campbell, co-director of the Fournoi expedition, about how to reach out to locals had started back 2012.“Many marine archaeologists use a lot of expensive equipment and spend endless hours searching the seabed,” says Campbell. “I find that the best way is to speak to the local community. They know where everything is.”

The American archaeologist has already used this approach off the coasts of the US, Jamaica and, more recently, Albania. “It’s not always easy. Often, you show up as a foreigner and they wonder who you are and what you’re doing there and whether you’re going to take stuff away. So it takes a lot of time, often years, and usually that involves just showing up year after year after year and then the information starts coming. Through that kind of communication we start earning their trust.”

Koutsouflakis hails from Icaria but does not believe that his credentials as a fellow islander helped much. It was his approach that made the locals trust him. He never kept any secrets from them or gave the impression that they were being blocked out. “As soon as we arrived, we held an open meeting at the town hall so we could tell people who were were and what we were doing,” he says. “Anyone can come visit the conservation workshop at the main port of Fournoi. The locals understand that what we’re doing is for the good of the community.” In this respect, Mytikas formed an important link with the community of fishermen and has been trying to convince them to reveal anything they know about shipwrecks in the area.

“When the archaeologists first arrived, we were afraid to talk,” says 33-year-old fisherman Smalis Olympiadis. As he explains the fishermen were concerned that areas containing finds would be listed for protection and fishing would be banned.

© Enri Canaj

THE CROSSING

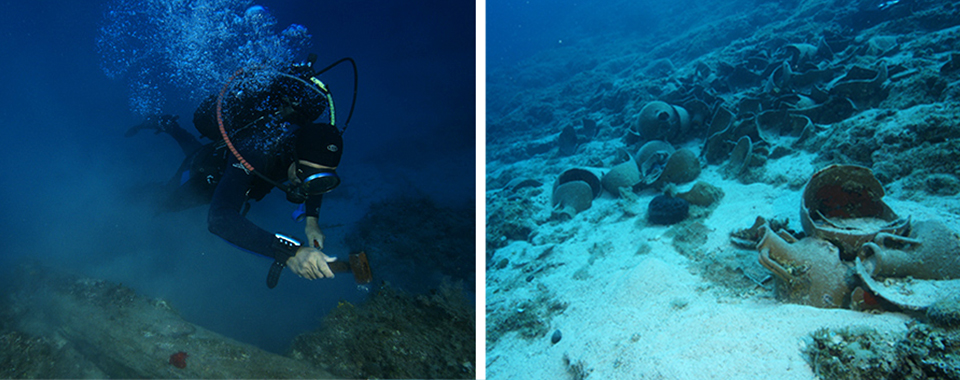

Only a few minutes have passed since the archaeologists dove down to a spot off the northern coast of the islet of Aghios Minas, where a wreck was discovered earlier this year at a depth of between 37 and 48 meters. They have already taken photographs and carefully dislodged a particular type of amphora from the sea floor. Now they will be bringing it up to the surface.

Sitting in a boat named Nautilus, Koutsouflakis looks for the bubbles that indicate they are coming up. It takes two people to hoist the amphora onto the inflatable craft. Deposits on its surface have made it much heavier but it looks to be in perfect condition despite centuries on the seabed.

At least three more wrecks have been discovered in this area. Koutsouflakis explains that the Fournoi islands have a lacy, varied coastline with lots of bays all around, ideal for anchorage. “Whatever the direction of the wind, a sailor will find shelter somewhere on the islands. This is a quality few Aegean islands can claim,” says the archaeologist.

“Icaria and Samos form a wall on the east-west axis whose only opening is through Fournoi. Ships sailing along this axis are more or less forced to pass the strait. When you have frequent passages, some ships – statistically it may be a very small number – will inevitably sink because of bad weather. If you add the passage of time to the equation, then it is safe to say that there is a large number of shipwrecks here.

© Illustration by Philippos Avramides

“In a sense, this underwater wealth has become incorporated into daily life on the island,” says Koutsouflakis.

Among the biggest finds last year was a wreck with Samiot amphorae from the 6th century BC. This year’s retrievals include a stone anchor that needed to be towed to port. “We are talking about a treasure trove. We have wrecks from different periods and amphorae of different typology and provenance,” says Simosi. Spongedivers from Kalymnos and the fishermen of Fournoi have been well aware of this treasure for decades.

“The wrecks have been badly plundered, especially those that are at a depth of less than 40 meters,” says Olympiadis. “They didn’t know that the amphorae were used to transport oil or wine. They thought they carried treasure and would smash them to look for gold coins.”

For others, the amphorae were used to decorate their homes or to give away as gifts. “We kept them for sentimental reasons in a corner of the house or gave them to friends. We didn’t regard them as valuable,” says fisherman Mainas Sklavos. A walk around the streets of Fournoi provides evidence of this.

A small amphora decorates the wall of a cafe, hung beside an old musket, while a larger vessel has been turned into a flower pot. Another amphora is seen built into the wall of an abandoned house, while three fragments of ancient pottery adorn the threshold of a shop.

© Enri Canaj

© Enri Canaj

A rare legacy

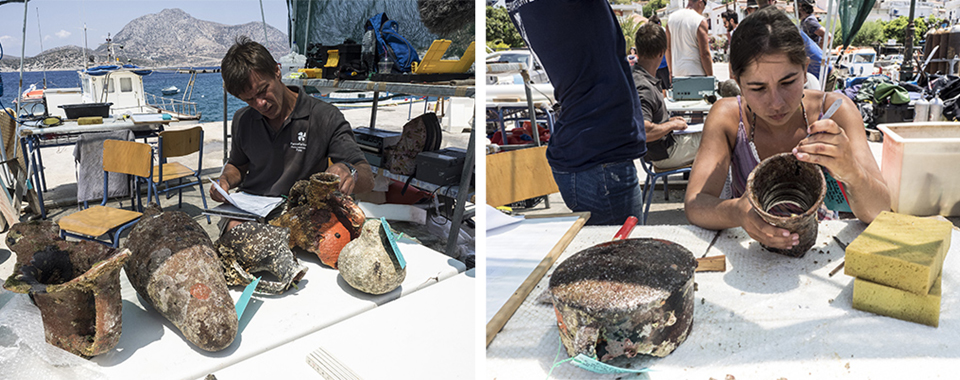

Every day brings new finds for the archaeologists and divers of the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities and their American colleagues. At the workshop in the port, conservators are busy cleaning the antiquities in large tanks filled with seawater, then vacuum packing them in special cases and preparing them for shipment to Athens.

When they reach the ephorate, near the Acropolis in the capital, they will undergo acclimation in freshwater tanks in a process that can take up to several months, before being restored.

The Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities turns 40 this year and it is not without problems. Chief Angeliki Simosi explains that its divers have been uninsured since April 1 and cannot conduct any dives until the Culture Ministry finds a way of coming up with the 40,000 euros needed.

Back at Fournoi, the municipal authority is doing what it can to help the archaeologists. Mayor Yiannis Marousis has called on locals to be more forthcoming with information or to hand in any antiquities they may possess. He already has an ancient stele in his office that was surrendered by one of the islanders. “I believe that people will start talking and opening up their treasure chests,” he says.

© Enri Canaj

“Mayor Marousis hopes that continued research will help the islands acquire a well-documented historical identity.”

On a recent night the locals were chatting about the new archaeological findings. When Koutsouflakis sat at a restaurant with the rest of the crew a waiter approached him and shared an information about a sea cave with antiquities.

The truth is that not all the tips are reliable and some stories need to be taken with a big pinch of salt. There’s been a story going around for the past 30 years, for example, that there’s a statue located somewhere between Fournoi, Kamari and Aghios Minas. “We’ve heard it from different sources but have not found any evidence that it exists,” says Koutsouflakis. “It’s a charming story that excites the imagination.”

Mayor Marousis hopes that continued research will help the islands acquire a well-documented historical identity. He says he would like to create a small museum in the area with some finds from the sea. What he knows so far is that the archaeologists’ expedition will continue until 2018. They are also pondering the possibility of a marine park or an underwater archaeology center to train students from around the world.

© Enri Canaj

Turning to tourism

The possibility that this underwater treasure may be exploited is of interest to many locals, who have traditionally made a living from fishing – there are 300 licensed fishermen on the island of 1,000 residents – and have been seeing their catch drop over the past few years.

“The sea does not bring in what it used to. The answer now is tourism. If we can get tourists to come, we’ll have work,” says retired fisherman Giakoumis Sklavos, who recently pointed archaeologists to three wrecks.

“We’re waiting to see what they’ll do but we don’t want these assets going elsewhere; we want the island to benefit.”

More fishermen are starting to talk as the mind-set changes and they realize that even if an area is declared protected it will have only a minor effect on their fishing grounds. Mytikas handed over a stone anchor he found at sea. He never considered asking for money, even though he is entitled to it by law. “I’m not looking to make a single euro from this business,” he says. “Once you start getting paid for something, it’s no longer a contribution.”

Fisherman Minas Sklavos is not looking for money either. “I’d be thrilled if they named a wreck I’d found after me – unofficially,” he says. “To know that I too am a part of my island’s history.”