I’ve always imagined paradise as a great big table strewn with platters, plates, bottles, glasses, baskets of bread and meat piled high on greaseproof paper. There’s a crowd gathered around these delights – kith and kin; acquaintances we’ll soon come to know better; and passing strangers who stop for a bite and whose faces or mannerisms pique our interest. We tease or bait them and await their response. The music plays on, competing with the small talk and the flirting. Sometimes that great big table is a bed, a wrestling ring, an art studio or a theater, but whatever it is, the party never stops.

Here in this real world, however, that’s not how it happens. Someday we’ll simply retire to the shade of a tree for an eternal nap, freeing up our seat at the table for the next person.

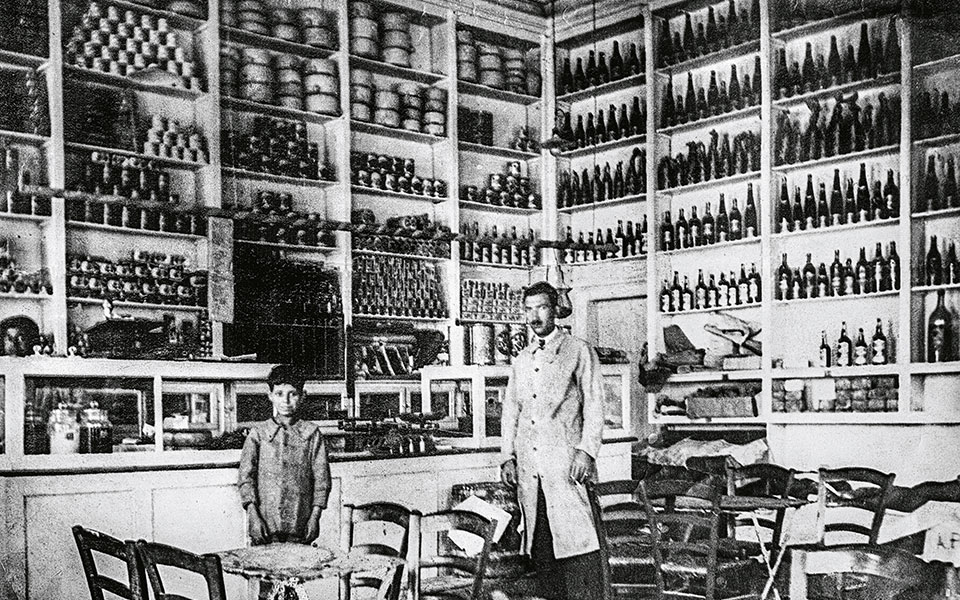

© Vassilenas Family Archive

Even as a teenager, I regarded any date with a girl as involving a meal. The food scene in Athens was much, much different back in the 1980s. It had a few hip restaurants like Iridanos and Papakia in the area known as Hilton, named after the hotel, and classic dining halls of 50 or more tables, like the Kentrikon on Kolokotroni Street or Ideal on Panepistimiou. The GB Corner, on the ground floor of the Hotel Grande Bretagne, served dishes such as “Athenian” grouper or “Texas” chicken – composer Manos Hadjidakis and poet Nikos Gatsos could be found there most days, having lunch with their students. Five minutes up Lycabettus Hill on foot, Gerofinikas titillated its patrons’ tastebuds with delicacies that included Lobster Thermidor. L’Abreuvoir at the end of Xenokratous Street has been preaching the joys of French cuisine since the early 1960s, just like its twin in Kifissia, Blue Pine.

In this thriving scene of family restaurants, waiters would appear from the kitchen carrying massive wooden trays laden with assorted plates of meze and diners would call out “Grab some fried zucchini! A tzatziki! A saganaki!” Every neighborhood had its local “koutouki,” too, with a sign that said “Wine and Grill” at the entrance, telling you precisely what it was. The koutouki proved, in fact, to be the most adaptable and durable of Athens’ eateries.

A tsunami of change has since swept across the restaurant business in the Greek capital. In anticipation of the 2004 Athens Olympics, the turn of the millennium brought lobster pasta and exotic wines. Every self-respecting restaurant stocked its wine cellar with bottles from Chile, New Zealand or South Africa and placed a cigar humidor in a position of prominence. Greeks were asked to eat (admittedly delicious)ostrich – and more than a few businesspeople invested in ostrich farms. We discovered beer-fed Kobe beef from Japan – at astronomical prices – and you could even try kangaroo ribs if your budget stretched that far.

© Dimitris Vlaikos

© Dimitris Vlaikos

A couple of years later, it started raining sushi. Every third restaurant seemed to have a counter in the back and a couple of Japanese chefs, dressed like surgeons, rolling up sheets of nori. A dish that was the people’s food back home was cast here as the pinnacle of sophistication. A little later, it was truffle – grated or shaved over pasta, meat or almost anything else – whose pungent aroma filled the air. The connoisseurs, who were probably right, sneered and favored the temples of “nouvelle cuisine.” You’d order a moussaka and get presented with a small brown ball in the middle of an otherwise empty plate. You’d crack it open, releasing, as though by some miracle, the flavors of minced beef, eggplant and spices. It really was moussaka: moussaka for astronauts.

In 2010, the Greek state went bankrupt. Society was thrust into a deep crisis. Gone were the days of maki and sashimi. Gone, too, for most were the tartares. And if you could still afford to pay for them, you were looked upon like a black marketeer. You were better off standing in line at the food truck for a couple of souvlaki with pita and eating them on a park bench.

Now, at the tail end of the pandemic and despite the war in Ukraine, the energy crisis and inflation, Greece is back on the path of recovery (or at least it feels that way). “Dining out” has returned in full glory. New restaurants are popping up every week, and innovative culinary concepts are being put to the test by the public. With such a plethora of choices, it’s tough to find your way and avoid becoming a disappointed diner lamenting the cost of dinner and venting your frustration with scathing reviews on social media. There is, perhaps, one way to prevent getting lost, and that’s by starting with establishments that have long, deep, roots.

© Dimitris Vlaikos

The master of all Greek prose writers, Alexandros Papadiamantis, has given us beautiful descriptions of the Athenian food scene at its birth. The setting is an “edodimopoleion” – a grocery store, basically – in the mid-19th century. Rather than taking their purchases to go, male patrons want to enjoy them on the spot, in the company of others. So, instead of wrapping the cheese and cold meats in paper, the proprietor lays them out on a table and fills a small metal jug with wine from a wooden cask. Over time, the grocer installs a stove, buys a pot and commissions his wife or daughter to cook up a dish – perhaps even two – every day, using their fine olive oil. And with those simple steps, the grocer becomes a taverner. It’s a story so familiar that it’s almost trite. But what is so interesting about it is that at least three restaurants doing brisk business in Athens right now are survivors, or descendants, of the classic grocery store-turned-taverna.

Leloudas is in Votanikos, a district once packed with blue-collar workers and local toughs, or “manges,” immortalized in such great rebetiko songs as “Votanikos’ Mangas” and “A Mangas in Votanikos.” The residential population has dwindled in recent years, leaving behind manufacturers, warehouses and depots. Leloudas, however, has remained steadfastly put, on a 6,000-square meter plot divided between 26 owners (property ownership in the greater Acropolis area is often as fragmented like this; apart from the Plaka, these districts were once tightly jammed with small structures and alleyways). It has just four tables outside, on the narrow strip of Salaminas Street, and another dozen or so inside.

Leloudas is a family business. The present owner’s grandfather came to Athens from the island of Kythnos before WWII. He started working wherever he could to earn a day’s wages, either at the local factories or at the grocery and wine store run by his sister and her husband. Eventually, he took over that business. He never had a home of his own, instead spending nearly half a century with his wife and children in the room next to the storeroom with the wine barrels. In 1972, he was succeeded by his son and daughter-in-law, and they, in turn, gave way to their son, who took over management in 2004.

This history is conveyed through a series of photographs on the walls – the oldest depicts the present owner’s great-grandfather on a boat in the Aegean sometime in the 19th century – and by the tales the present owner shares with his patrons: “On November 8th, 1990, it was sleeting in Athens. At daybreak, my father filled one of the big barrels, those holding 850 liters, and by midnight all the wine had been consumed … We demolished the original store in 1995; it was little more than a shack, without a proper restroom even, and built the building you see today … The taverna used to stay open from lunch until late at night. But people started moving out of the neighborhood, and unsavory types started hanging around, snatching our customers’ purses. I had enough and decided to start closing at five in the afternoon.” The menu at Leloudas also remains largely unchanged: meatballs with fried potatoes; lamb in a lemon sauce; fried cod with garlic puree; and fava dip. The dairy products from Kythnos have, however, been removed because they weren’t certified. One menu item I’d never tried before is called The Poor Man’s dish: fried potatoes topped with minced meat and grated cheese. For just €15, you can throw your taste buds a party in a location that feels like the set of a neorealist film.

The eatery Oikonomou shares a similar past to Leloudas. In the early 20th century, a man from Trikala traveled to Athens and opened a small diner in the then-poor neighborhood of Petralona, serving meat soup, tripe soup, and vegetable stews. Here, however, the similarities end. Over time, this modest taverna became an institution in a neighborhood that boomed rather than declined. It invested in the future in 1951 with the purchase of an Altis refrigerator that still works and even earned the praise of a Financial Times correspondent. In 2000, Kostas Diamantis purchased the taverna by paying Oikonomou’s son an amount equal to two years’ worth of good earnings. He spent an equal amount renovating it, with loving care, to a high professional level. He expanded the menu, adding Epirot pies, lamb fricassée, pork with leeks and celery, rooster with okra, and other highlights of Greek cuisine.

Today, Oikonomou is a hangout for artists and intellectuals and a magnet for any foreigners yearning to acquaint themselves with the local cuisine. Even the Greek president used to eat here at one time; after all, Petralona is now one of Athens’ most popular alternative areas, with bustling bars and outdoor movie theaters.

Good-natured and smart as a whip, Kostas Diamantis always does the rounds of the tables. He chats with his patrons, forges friendships and gets invited to the theater by the actors. As is true of any good taverner, he is also a barometer of the country’s social and perhaps even political weather. As he tops up wine glasses and serves platters of cheeses on the house – manouri, feta, and kefalograviera – he gets a whiff of every development in the offing.

The eatery Vassilenas is proof that initiative and diligence are hereditary. The present owner’s grandfather, another grocer-vintner, had the brilliant idea back in the 1920s to bring packaged meals to the factory workers of Piraeus; it was Greece’s original take-out service! His food was delicious, and even the bosses loved it, so they started hanging out at his taverna along with the workers.

The second innovation came a few years later: diners would no longer choose what they ate. Instead, in what was known as table d’hôte at the time, Vassilenas himself would determine a succession of dishes, composing a symphony of flavors in 10 to 15 parts.

Once WWII ended, and as Piraeus became a center of international shipping, Vassilenas’ reputation skyrocketed. No one of any prominence could visit Greece without making a stop there, not Winston Churchill, Tyrone Power, or Elia Kazan. The homegrown elite dined here as well. The Nobelist poet George Seferis even mentions Vassilenas in his journal. for his part, Vassilenas (and his son after him) collected the handwritten cards of praise from patrons, the rave newspaper reviews in different languages, and the photos snapped by paparazzi of celebrities at his establishment. Father and son enjoyed the recognition. Nevertheless, they firmly believed theirs was a “bakalotaverna” (a grocery store-taverna) and that it should remain such, retaining the mark of their provenance in the decor and the food they served.

In 2005, the grandson of the taverna’s founder moved Vassilenas from Piraeus to the central Athens district of Ilissia and turned it into a luxury restaurant. Did he divest it of its unique character? If you’re nostalgic, then yes. Little is left from the historic menu save the famed taramasalata. The atmosphere is no longer alive with accordions, guitars and singing; it is professional and sophisticated. But Thanassis Vassilenas, a brilliant man and entrepreneur, stands by his choices. He’ll tell you there was no point in this rapidly changing world risking ending up a guardian of tradition and little else, the owner of a mausoleum to days and people long gone. And if his arguments fail to sway you, his food will: meat dishes and seafood options of the highest quality, the highly original creation known simply as “Egg,” and a great red mullet savoro, a dish I doubt is served anywhere else in Athens.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

© Angelos Giotopoulos

Linou Soumpasis kai Sia is the result of the work of Myrsini Linou and Giorgos Soumpasis, who, like Napoleon who boasted that his success was all of his own creation, can claim all the credit for the excellence of this establishment. In late 2021, they leased space in Psyrri, revamped it in a minimalist style (with aluminum playing a key aesthetic role), and launched their restaurant. How can I describe the result? It’s postmodern, in the sense of combining disparate elements. That starts with the sign, Linou Soumpasis kai Sia; how long has it been since we saw a business named after its owners? There’s also the fact that the restaurant acts as a candle shop, too. It all seems a little silly at first – but then the food and wine make their appearance.

The food comes from Lukas Mailer, an inspired chef who, despite being so young, had already made history on the island of Lemnos, that culinary paradise in the northern Aegean, before joining the team in Psyrri. With a bit of cajoling, Soumpasis brought him to Athens, where Linou gave him carte blanche in the kitchen. The result includes a finger-licking half rooster (with visible spurs) slow-cooked in a clay pot. A salad of boiled vegetables is so delicious that it’s like nothing I’ve tasted before. There’s tomato juice in a bowl where you can dip your bread,and fragrant organic wines to go with it all, including an enchanting orange Malagousia.

Everything is in play at Linou Soumpasis kai Sia. There’s no fixed menu; the chef improvises with what the market offers that day. There’s no “target audience” either; it’s a social mix-and-match that’s very welcome in an age when people tend to buttress themselves behind labels, to navel-gaze with like-minded spirits and to wage war against “others.”

The only condition to this fete of flavors? Being able to afford the €150 it costs a couple to leave the restaurant feeling hearty, tipsy and happy. “If we lowered the prices,” say the management, “we’d also have to lower the quality.” It’s an honest statement.

© Katerina Avgerinou

CTC Urban Gastronomy confirms my belief that a restaurant’s success should not be judged by its effect on the tastebuds and stomach but on the mind and spirit. A great meal out includes fascinating conversation, fertile arguments, new collaborations and budding romances, where groups of friends suddenly feel compelled to sing, occasionally rousing others to song as well. The food and the drink are there to help this magic happen and, ideally, you’ re so carried away by the company you can’t even remember just what it is you’re eating and drinking even though this is, in fact, the fuel of your bliss.

If it’s in your nature to spend two and a half hours dedicating yourself to flavors and heavenly food aromas, you should book a table at CTC Urban Gastronomy. A table for one would probably be best, as there’s little chance you’ll be interested in anything beyond what’s on your plate and in your glass.

It’s not the Golden Toques or the Michelin star that counts, it’s the chef: Alexandros Tsiotinis. Raised in the Athens suburb of Patissia and initiated to food in Paris, Tsiotinis is an inspired artist. His menu comprises 11 dishes whose exact natures are kept secret from the uninitiated diner, just like the ending of a film might be, and seven different wines that complement the food to perfection. The vision? To elevate Greek cuisine to the stars, taking it to its apogee. It’s a vision that isn’t betrayed by the execution.

A warning: we’re about to reveal some of that menu, which includes a combination of spinach pie and lobster with avocado cream to set the tone, followed by corn chowder, then calamari with a pesto sauce and a hint of garlic, the fresh fish of the day with a soupçon of caviar, and lamb with a simple dressing of olive oil and lemon. The servers explain each dish and the sommelier delivers brief lessons in his craft as he pours.

The most fantastic thing of all may be the dessert: half a peach perched on icing sugar appears before you, but as you start eating, you discover that the flesh is white chocolate and the pit is its dark counterpart. It’s Disney’s “Fantasia” in dessert form. Speaking without bias, CTC Urban Gastronomy is at the pinnacle of the culinary Olympus.

Can the aftermath of an excellent meal be like that of a sexual encounter? With food, can there be something like post-coital tristesse, the melancholy that follows an intense orgasm, when “the devil’s laughter is heard,” as Schopenhauer says? I believe so. And there lies the grandest – and quite ridiculous – of human tragedies; we will do anything for a meal, a drink, and a night of love, as though chasing our own tails…