Discovering Archaeology in the Athens Metro

Beneath the busy streets of modern...

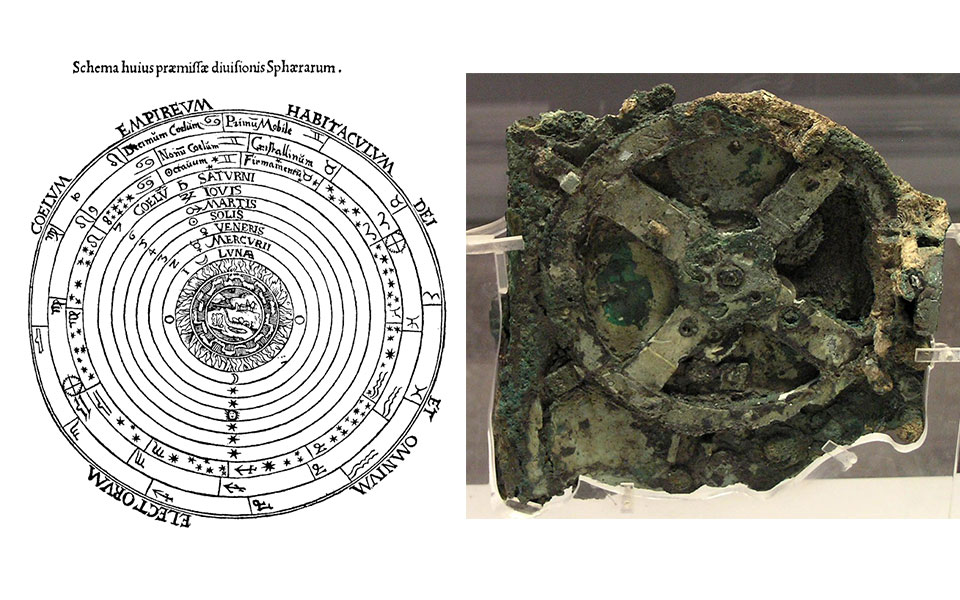

Constructed sometime in the late second or early first century BC, the Antikythera mechanism is widely regarded as one of the most important archaeological discoveries in history.

© National Archaeological Museum, Athens

If you’re a dyed-in-the-wool Indiana Jones fan like me, there’s a good chance you’ve already seen “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny,” the latest installment in the hit Hollywood franchise. If not, and you’re still planning to go, don’t worry: I won’t reveal any plot spoilers!

Even if you’ve just seen the trailer (see below), or followed the buzz surrounding the film’s release, you’ll know that the story revolves around a highly fictionalized version of the renowned Antikythera mechanism, an extraordinary artifact that was discovered at the site of an ancient shipwreck, off the coast of Greek island of Antikythera. In the film, the mechanism is used as a “mapping device” (enough said!), but how much do we know about the actual mechanism and its intended function?

Since its discovery in 1901, the mysterious Antikythera mechanism has fascinated and baffled scientists in equal measure. Initially, its significance eluded scholars – the severely corroded and fragmentary state of the mechanism made it impossible to discern its purpose or origin – but later studies in the 1950s and 60s, using newly-developed X-ray imaging, enabled scientists to gradually unravel its secrets.

Here, we consider how it was built, describe its likely function(s), and put forward a few ideas about the extraordinary inventor(s) who may have been behind its ingenious design.

In October 2001, a team of underwater archaeologists revisited the Antikythera wreck to gather data for a high resolution photogrammetric map of the site.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities

The Antikythera mechanism was discovered in the summer of 1901, during an underwater expedition to retrieve artifacts from an ancient shipwreck off Point Glyphadia on Antikythera. The site had been discovered the previous year by a crew of sponge divers from the island of Symi, sailing through the Aegean en route to fishing grounds off the coast of North Africa.

Lying at a depth of 45m, archaeologists would later determine the wreck to be of Roman origin: a cargo ship that sank within a few years after 70 BC, carrying numerous artifacts, inlcuding life-size bronze and marble sculptures, ceramic vases, glassware, and bronze sounding weights. Amid the wreckage, the divers, wearing canvas suits and copper helmets, retrieved a heavily corroded lump of bronze – a “concretion” – which was sent with the rest of finds to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens for conservation and analysis. Little did they know at the time that they’d made one of the most important discoveries in the history of archaeology.

In May 1902, nearly a year after its recovery from the shipwreck, Greek archaeologist Valerios Stais spotted intricate gear wheels and fragments bearing inscriptions in ancient Greek, embedded in the concretion. Stais’ observation sparked a frenzy of intrigue and speculation within the scientific community, and the shoebox-size object soon became known as the “Antikythera mechanism.” But what was this mysterious device used for? And where did it come from?

Theories abounded for half a century before renowned British physicist and science historian Derek J. de Solla Price, in 1951, took up the challenge of deciphering the mysterious object. Using newly-developed X-ray imaging and meticulous analysis of the extant fragments, Price’s investigations showed that the device was a masterpiece of mechanical engineering: an astronomical calculator, capable of predicting celestial events, such as lunar and solar eclipses, planetary positions, and the cycles of the ancient Greek calendar, including the quadrennial Olympic Games.

What is perhaps most remarkable about the mechanism, described as the world’s first analog computer, is that its level of advanced technology and precision engineering would not be achieved again for another thousand years.

Described by scientists as the world's oldest analog computer, the Antikythera mechanism was used to track celestial movements, predict astronomical positions, and display various astronomical cycles.

Scholars have long debated the date and provenance of the Antikythera mechanism. Its construction relied on astronomical and mathematical theories developed during the second century BC, at the height of the Hellenistic period (323-31 BC), a time of extraordinary intellectual and scientific achievement – the ancient Mediterranean equivalent of the European Renaissance. Current theories place its construction sometime in the late second or early first century BC, with one study proposing an earlier date of around 200 BC.

The mechanism was built using a combination of advanced metalworking techniques, including casting and milling. Of the 82 known fragments, the main components were made of bronze, a durable and corrosion-resistant alloy commonly used in ancient Greek technology. These were cast into various shapes, forming the gears, plates, and other mechanical parts.

The gears, which were essential for its complex calculations and movements, were intricately crafted. Their teeth were likely cut using a milling technique, which involved rotating a cutting tool against the metal to create precise and consistent profiles. This process required extraordinary skill and precision to achieve the desired gear ratios.

Encased in a wooden box, about 30cm tall, the surfaces of the gears and plates were then engraved with minute inscriptions and markings, providing information about celestial bodies, astronomical cycles, and other relevant data – a kind of built-in user’s manual. A recent international study, using cutting-edge scanning equipment, detected more than 30 bronze gearwheels connected to dials and pointers, and 3,500 characters of text on the inside of the device, each of the letters a mere 1.2mm in size.

Given the mechanism’s complexity, it is believed that multiple craftspeople with specialized skills collaborated in the its construction; individuals with advanced knowledge in astronomy, mathematics, mechanics, and metalworking. While the precise workshop or location where the mechanism was built remains unknown, it’s likely that it was constructed in a center of great technological innovation, such as Alexandria or Rhodes, where scholars and craftspeople could share knowledge and collaborate on such sophisticated projects.

Cutting-edge scanning equipment was used by international scientists trying to decipher 3,500 characters of text on the inside of the 2,100-year-old artifact.

After a century of research on the Antikythera mechanism’s surviving fragments, scholars agree that it was a hand-powered astronomical calculator, with a range of different functions. It was primarily designed to predict celestial events, which it did by tracking the positions of the Sun, the Moon, and the five known planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn), the phases of the moon, and the solar and lunar eclipses.

The device also included features used to calculate phenomena in the ancient Greek calendar such as the Metonic cycle (or “enneadecaeteris”), which refers to a 19-year lunar cycle in which the phases of the Moon are repeated on the same days of the year, first observed by mathematician and astronomer Meton of Athens in the 5th century BC. The mechanism was also used to calculate the timing of Panhellenic athletic games – a function of the so-called “Games” dial – such as the Olympic and Nemean Games, and the Halieiad, celebrated on the island of Rhodes in honor of their patron god Helios, the Sun.

The mechanism may have been used for tracking the positions of certain stars and constellations. Some scholars suggest that it might have featured a “zodiac dial” – the front face features two concentric circular scales, the inner scale marking the twelve Greek signs of the zodiac. As such, the device may have calculated the changing positions of the Sun and Moon in the zodiac throughout the year. This function would have been especially useful for navigation at sea.

In a recent international study, Professor Alexander Jones at New York University, a team member in the research, believes the mechanism was actually a “philosopher’s instructional device.”

“It was not a research tool, something that an astronomer would use to do computations, or even an astrologer to do prognostications, but something that you would use to teach about the cosmos and our place in the cosmos,” reported Jones in 2016. “It’s like a textbook of astronomy as it was understood then, which connected the movements of the sky and the planets with the lives of the ancient Greeks and their environment.”

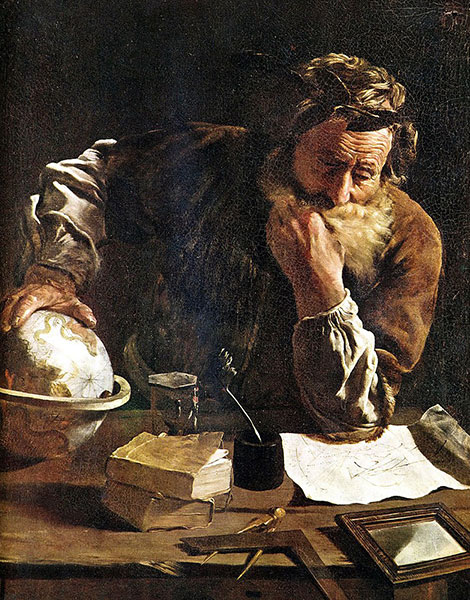

"Archimedes Thoughtful," by Domenico Fetti (1620)

© Public domain

A modern reconstruction of the Antikythera mechanism.

The identity of the individual or group of individuals who designed and built the Antikythera mechanism remains a mystery. While no historical records or inscriptions provide any direct information regarding its creator(s), a popular theory is that it was the work of renowned mathematician, physicist, and inventor Archimedes (c. 287-212 BC), who was born in the city of Syracuse, a former Greek colony on the east coast of Sicily. This is based on his known work on astronomical observations, including solar events, as described in the later writings of Alexandrian mathematician and astrologer Ptolemy (c. 100-170 AD), as well as his advanced knowledge of differential gearing.

In “De re publica” (On the Commonwealth), an extensive dialogue on politics and constitutional theory by the Roman statesman Cicero (106-43 BC), two bronze mechanisms that track the motion of the Sun, Moon, and the five known planets, both attributed to Archimedes, are described in some detail. The devices were brought to Rome by Marcus Claudius Marcellus, the general who led Rome’s two-year siege of Syracuse (214-212 BC), during which Archimedes was tragically killed (against the orders of Marcellus).

Another theory, again based on the writings of Cicero, is that Greek mathematician, astronomer, and Stoic, Posidonius of Apameia (or “of Rhodes”) (c. 135-c. 51 BC), constructed the Antikythera mechanism sometime in the late second century or early first century BC. In his “De Natura Deorum” (On the Nature of the Gods), Cicero describes how Posidonius constructed an orrery that exhibited the diurnal motions of the Sun, Moon, and the five known planets – a device that is conspicuously similar to the Antikythera mechanism.

Another possibility is that the Antikythera mechanism was a collaborative effort involving a group of skilled craftspeople, astronomers, and mathematicians who shared their knowledge and expertise. As mentioned, it might have been created in a center of technological and intellectual activity, such as Alexandria or Rhodes, where scholars and inventors gathered to exchange ideas and push the boundaries of knowledge.

The Antikythera mechanism is one of the prize objects at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

© Shutterstock

The fragments of the Antikythera mechanism are currently on display in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, alongside a modern replica.

Earlier this year, the museum website launched an online educational program, “The Mysteries of the Mechanism of Antikythera,” aimed at young visitors. The interactive bilingual app (in Greek and English) enables users to study and explore the various aspects of the famous mechanism, from its initial discovery in 1901 to its later analysis and conservation, by following one of seven scientific specializations.

To visit the app, click here.

Several replicas of the Antikythera mechanism are on display in science and technology museum collections around the world, giving visitors the chance to learn about its significance within the broader context of human technological achievement. These can be found at the American Computer Museum in Bozeman, Montana, at the Children’s Museum of Manhattan in New York, at Astronomisch-Physikalisches Kabinett in Kassel, Germany, at the Archimedes Museum in Olympia, Greece, and at the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris.

So, after all that, are you intrigued to see how the famous mechanism is depicted in the new Indiana Jones movie?

Beneath the busy streets of modern...