Why Now Is the Best Time to Discover...

Explore Ancient Messene, enjoy the local...

The Tholos (380 BC), at the Temple of Athena Pronaea, is a masterpiece of the Classical period and perhaps the best-known monument at the archaeological site of Delphi.

© Perikles Merakos

On the day I made my way up to Delphi for the first time, along with many other visitors from Greece and abroad, the sunshine, the light mountain breeze and the enchanting landscape above the Pleistos valley left little doubt that I would fall in love with the moment and the place. And this is precisely what happened to me and what must have been happening to first-time visitors for centuries.

It helps, nonetheless, to be prepared. The “well-informed” visitor, or whoever comes accompanied by a qualified tour guide, is certain to live the Delphic experience to the fullest. It’s important to note this. There are also interactive applications, developed by the Ephorate of Antiquities of Fokida, which you can download to your mobile phone.

Otherwise, you might see, for example, a temple-shaped building and read the sign “Treasury of the Athenians” without realizing that Athenian hoplites dedicated their shields here to the god Apollo as a token of gratitude for their victory at the Battle of Marathon (though not the Athenian general, Miltiades, who dedicated his helmet – which is on display at Olympia – to Zeus). You may also recall stories about the Pythia, the high priestess who sat atop a tripod seat, chewed bay leaves, and delivered oracles in an ecstatic trance state. However, would you know that, according to certain geological studies, the Temple of Apollo, where these rites took place, may have stood above the intersection of two fault lines, which might have allowed gases to accumulate in the oracular chamber causing confusion, mild amnesia, and so on? The uninformed visitor, looking at the foundations of the Temple of Apollo, one of the most important gods in ancient Greek mythology and Artemis’ twin brother, will be unaware that worship of this god began in the 8th century BC, replacing the worship of Gaia, the primordial chthonic goddess who preceded Apollo at Delphi.

Similarly, the unenlightened may not be aware that the basic principle of the Apollonian spirit, as explained by our licensed tour guide Vassi Traka, was the taming of human passions on both a collective and personal level, gradually leading the ancient Greeks to adopt humanitarian values. Our knowledgeable guide also referred to a text by Panos Valavanis, a professor of classical archaeology, who claims that at the heart of Apollonian teaching are “two basic concepts of ancient Greek wisdom: moderation and self-knowledge. Which, not coincidentally, are the two fundamental principles in human history.”

The Dancers of Delphi (c. 330 BC). Three women with finely sculpted features are visible.

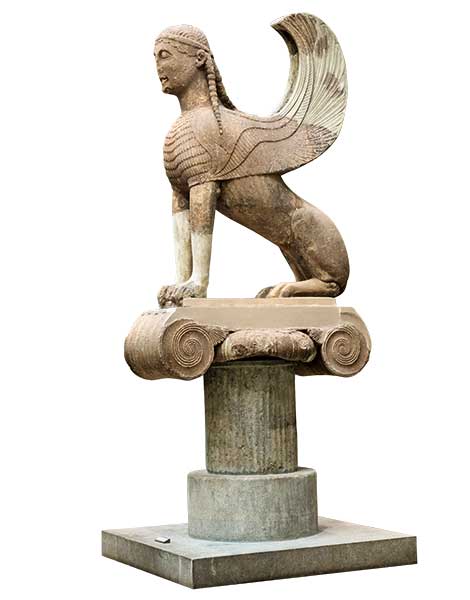

The impressive Sphinx of the Naxians, with a lion’s legs and body, the breast and wings of a bird, and the head of a maiden. It dates to 560 BC.

For over ten centuries, the Sanctuary of Delphi served as both a cultural and religious center, as well as a symbol of ancient Greek unity. It was the only place that was unaffected by wars or foreign enemies, including the Persians, during its heyday. Instead, all the Greek tribes banded together to protect the sanctuary, forming the Delphic Amphictyony. This league, which met twice a year, was similar in some ways to the modern United Nations.

Another phenomenon observed for the first time in the history of world civilization was Delphi’s ability to intervene as an intermediary in city-state conflicts. “The Sanctuary consented to the laws introduced by Lycurgus, the lawgiver of Sparta, and Solon, the lawmaker of Athens, while its contribution to Ionian colonization was decisive,” observed Traka. The oracle’s responses appear to have directly influenced the development of Greek and, by extension, Western civilization.

Some scholars believe that much of the wealth of the ancient world was gathered at Delphi. Although there is no concrete evidence to back up this belief, Athanasia Psalti, director of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Fokida, told me that, “Due to its strategic geographical position, the undisputed dominance of the worship of Pythian Apollo and the oracle throughout the Mediterranean basin, and the prestige of the Pythian Games, Delphi had become a place that attracted many offerings of particularly valuable objects – statues of silver and bronze, gold jewelry, elaborate sculptures, luxury vessels, bronze and solid gold tripods, bronze statues (such as Heniokhos, the amazing Charioteer of Delphi), and exotic ivory items, as well as ornately decorated architectural creations such as the Siphnian Treasury and the Athenian Treasury.”

The magnificent landscapes in the valley of the Pleistos River contributes to the overall Delphic experience.

It is known that the oracles delivered by the Pythia were inexplicit and ambiguous. Heraclitus provides the key: “Phoebus (Apollo) neither reveals nor conceals but gives a sign.” When a hoplite, concerned about his future, consulted the oracle, Apollo – through the Pythia – seemingly responded: “Ikseis afikseis, ouk en to polemo thnikseis” (“You will go, return you will, never in war will you perish”). However, simply changing a comma transforms the prophecy into: “Ikseis, afikseis ouk, en to polemo thnikseis” (“You will go, return you will never, in war will you perish”). And when the Athenians were alarmed by the advance of Xerxes’ army, the oracle delivered by the priestess at Delphi was again open to interpretation: “The goddess Athena cannot save her city. But the Athenians can be saved by the wooden walls.” As a result, the Athenians prepared to construct wooden walls around the city; but the politician and general Themistocles offered an alternative interpretation, claiming that the “wooden walls” actually referred to their ships, ultimately leading to a decisive Greek victory at the Battle of Salamis.

Aside from representatives of the city-states, Delphi also attracted private individuals who were burdened with troubles that have remained virtually unchanged over the centuries. In inscriptions that have been discovered, they ask if they should marry or have children, if they should purchase land, or if they will be cured of some illness. The aim of Apollo was to calm their passions, cure ignorance and serve the process of human evolution through his priests (the first priests at Delphi were Cretans who possessed the wisdom and knowledge of the Minoan civilization). The wisdom of Delphi, a legacy passed down through the centuries, was summed up in the Delphic maxims that were inscribed on the pronaos (and possibly elsewhere as well): moral precepts believed to have been authored by the Seven Sages of Antiquity and “useful for the life of men,” according to Pausanias. The 147 succinctly worded sayings are based on the values of the era, such as “Help your friends” or “Control anger.” The last item on the list is perhaps the most important: “On reaching the end, [be] without sorrow.”

The Charioteer of Delphi (478-474 BC), the museum’s most famous exhibit.

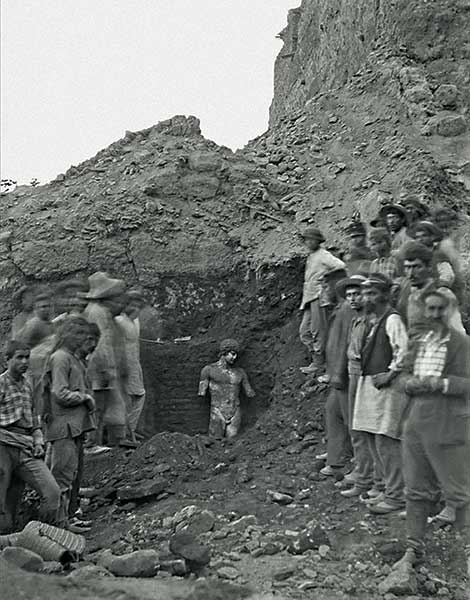

The excavations by the French School of Archaeology unearthed, among other finds, the splendid Statue of Antinous.

© French School of Athens Photographic Archives

It is worth keeping this last maxim in mind when touring the wonderful Archaeological Museum of Delphi, since there, among other famous exhibits, you’ll find the Kouroi of Delphi, two male marble statues thought to have been dedicated to Apollo by the Argives. They were previously identified as two young brothers who, according to Herodotus, were from Argos, which was said to be Europe’s oldest city. At some point, their mother, a priestess of Hera, asked them to yoke themselves to her cart in place of the oxen (which could not be found) and pull her to the temple for a festival. Their mother then begged Hera to give her sons the highest honor she could bestow on mortals. That night, the two brothers fell asleep but did not wake up, having been rewarded with a peaceful death while still in their prime. (However, the museum curators point out that a more recent interpretation identifies the two youths as the Dioscuri, sons of Zeus and Leda.)

The masterpieces in the Delphi Museum are many, but the most famous are the Charioteer, that majestic youth with his piercing gaze, and the imposing Sphinx of Naxos. I asked Psalti if there was perhaps an overlooked gem. “That’s a difficult question,” she replied, before continuing: “I greatly admire the Statue of Antinous, a young Greek of extraordinary beauty from Bithynia, beloved companion of the Roman emperor Hadrian, who dedicated the statue at Delphi after Antinous drowned in the Nile. It’s a nearly 2,000-year-old statue of a young man who died prematurely.”

© Shutterstock

The Statue of Antinous and the Charioteer were unearthed during the Great Excavation (“La Grande Fouille”), which was carried out by the French Archaeological School between 1892 and 1902 and involved the expropriation of the settlement of Kastri that had been built over the ancient site The historian and journalist Kyriakos Simopoulos points out that, until the 19th century, “very few foreigners made their way to remote and desolate Delphi during the centuries of the Ottoman occupation, and even fewer archaeologists searching for the remains of ancient Delphi.” The travellers George Wheler and Jacob Spon first identified the area as the Sanctuary of Delphi in 1676 but, with only a few exceptions, no systematic archaeological investigation was attempted until the arrival of the Swedish priest Adolf Fredrik Sturtzenbecker in 1784. The latter died prematurely in Livadia, shortly after his visit to Delphi. However, Simopoulos says, research trips by lovers of ancient history became more frequent thereafter. Although English traveler Thomas Smart Hughes found “a place worse than a pigsty” at Kastri in 1813, he did take some time to explore the ancient monuments, which by this point were attracting attention from all over the world. “The numerous foreign visitors to Delphi during the 19th century, from the English architect William Gell to the Swiss philhellene Alfred Gilliéron, made significant contributions to the sanctuary’s emergence from obscurity and to the strengthening of the memory of the famous oracle. Τhey thus helped the idea of the Great Excavation to mature,” said Psalti.

In 1903 the Archaeological Museum of Delphi opened following the conclusion of the Great Excavation. In its present form, the museum is a true gem of modernism, the work of several well-known Greek architects, including Patroklos Karantinos and Alexandros Tombazis. Nowadays, there aren’t many locations in Greece that can provide a visitor with complete intellectual, moral and aesthetic fulfilment, but the Delphi Museum is unquestionably one of them, thanks to its exquisite architecture, the outstanding curation of its treasures, and its location in a spot of such natural unspoiled splendor.

Last year marked the 120th anniversary of the the museum’s opening, as well as a decade since it was designated as an honored museum by the International Council of Museums (ICOM): “This was a very favorable and particularly instructive development in its long history, which contributed towards the museum becoming more deeply integrated into the life of the local communities that surround us. Even during the pandemic and the painful period of isolation, the inhabitants of Delphi, Amfissa, Chrysso and Itea stood at our side and supported our efforts,” noted Psalti, adding that there has been a noticeable rise in both Greek and international visitors. The magnitude of the legacy left by so many centuries of history and the significance of Delphi for Greece’s cultural life today cannot be overstated.

Delphi has long served as an inspiration for people and organizations active in the arts, history and culture who wished to establish important cultural institutions, including Angelos Sikelianos and Eva Palmer’s (1927-1930) Delphic Festivals, which arguably paved the way for modern performances at ancient theaters and for the Athens-Epidaurus Festival; the European Cultural Centre of Delphi, which was founded in 1977; and Theodoros Terzopoulos’ Attis Theatre, which was founded in 1985 and which held its groundbreaking production of Bacchae in the ancient stadium at Delphi a year later.

I asked Psalti if one ever tires of delving into the history and the other aspects of Delphi. “I don’t believe so, because of the enormous conceptual, intellectual and artistic value of the site,” she said, before adding: “Perhaps the words of the poet Nikiforos Vrettakos best capture the emotion that even we, who daily serve this place, feel each time we visit the oracle: ‘A teardrop is a language that speaks with countless words, / beneath the sanctity of the firmament, when you return from Delphi…’”

Explore Ancient Messene, enjoy the local...

Archaeology reveals powerful Iron Age women...

Why not try a brief getaway...

From olive presses and traditional costumes...