Car-Free Kea: A Cycladic Island Escape Near Athens

Just an hour from Athens, Kea...

The Britannic, sister ship of the Titanic, served as a hospital ship during WWI.

© Public domain

On November 21, 1916, as World War I raged, one of the largest passenger ships ever built, requisitioned by the British Admiralty to serve as a hospital ship during the disastrous Gallipoli Campaign in the Dardanelles, struck a German mine and sank to the bottom of the Aegean Sea. The ship in question was the majestic “Britannic,” the third and final vessel of the White Star Line’s famous “Olympic” class of transatlantic passenger ships, the younger sister of the RMS Olympic, and the ill-fated RMS Titanic.

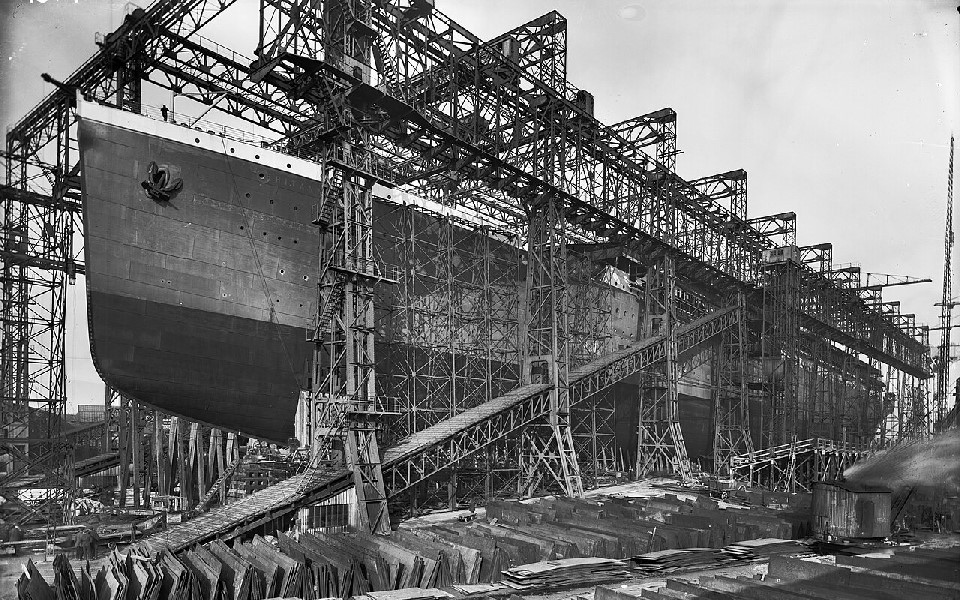

All three ships were built at the Harland and Wolff shipyards in Belfast, and, at the time, were the largest and most luxurious ships in the world.

Only one of the three sister ships went on to serve a long career as a luxury transatlantic liner, the other two sinking within several years of their launch. And while the sinking of the Titanic on April 15, 1912, with the loss of more than 1,500 passengers and crew, still captivates people over 100 years later, the fate of its sister ship, the Britannic, off a small Greek in 1916, is less well known.

The Arrol Gantry towering above Britannic, at Harland and Wolff shipyards, Belfast, c. 1914.

© Public domain

Following the sinking of the Titanic – still the deadliest peacetime maritime disaster in history – the White Star Line made significant changes in the Britannic’s design and construction to make it safer. It was intended to be company’s most luxurious ship, competing with the likes of Germany’s “SS Imperator” and “SS Vaterland,” and the RMS Aquitania, a colossal ocean liner from the rival British operator, Cunard Line.

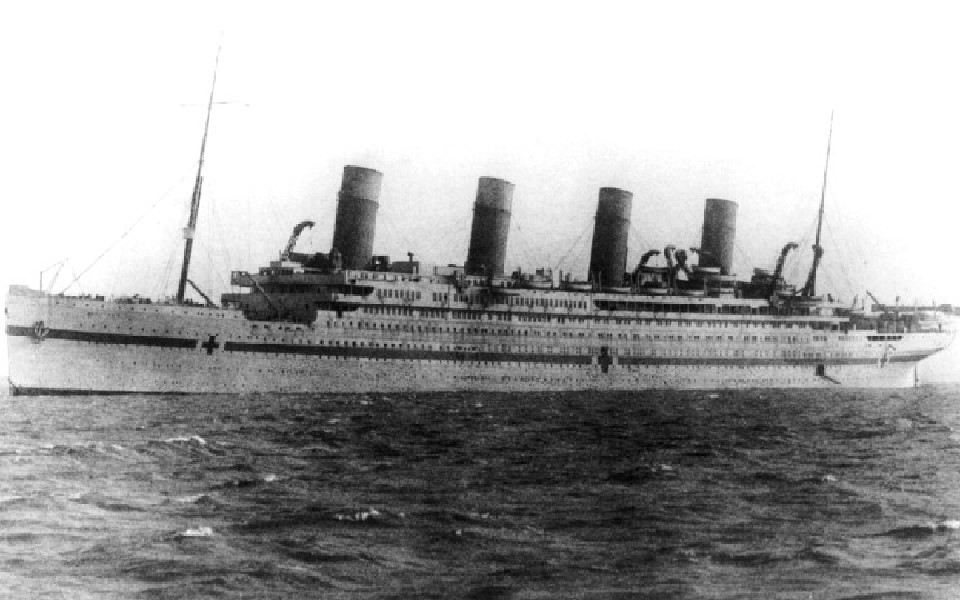

Changes in design not only strengthened the hull and increased the number of lifeboats (48 in all, compared to the Titanic’s 20), but also significantly improved the accommodation for First- and Second-Class passengers: each cabin was fitted with its own bathroom, something that the Titanic did not, and the grand staircase leading from the deck to the interior of the ship was even more magnificent than that of its sister ships, with luxurious wood paneling, and plans to install an ornate pipe organ.

The RMS Britannic at sea in her intended White Star livery.

© Public domain

Launched in February 1914, and completed on December 12, 1915, some 18 months into the start of World War I, the RMS Britannic was almost immediately pressed into service by the British Admiralty as a hospital ship (the similar-sized RMS Aquitania was used as a troop transport ship). With a maximum capacity of 3,309, and intended for transatlantic voyages between Southampton and New York, the Britannic was instead repainted white with large red crosses and renamed the “HMHS Britannic” (His Majesty’s Hospital Ship).

Common rooms on the upper decks were converted into wards for the wounded troops, while dining rooms and the large banquet hall intended for First-Class passengers were converted into operating theaters.

Under the command of Captain Charles Alfred Bartlett (1868-1945) – nicknamed “Iceberg Charlie” for his preternatural skill to “sniff out” icebergs from miles away – and with a complement of 101 nurses, 336 non-commissioned officers, 52 officers and a crew of 675, the newly painted HMHS Britannic made its way from Liverpool, England, to the eastern Mediterranean.

From December 1915 to October 1916, the ship completed five successful voyages to the Middle Eastern theater, bringing back to the United Kingdom thousands of sick and wounded troops. The floating hospital had performed remarkably well, and despite violent storms and the constant threat of underwater mines, the Britannic emerged unscathed.

Britannic seen after her conversion to an operative hospital ship, c. January 1916

© Public domain

On her sixth and final voyage, the nearly 50,000-ton Britannic set off from the port of Southampton on November 12, 1916. Her intended destination was the Greek island of Lemnos, in the Northern Aegean, to receive more wounded troops.

After a storm halted the ship’s progress for several days at the Port of Naples in southern Italy, the Britannic made its way through the Strait of Messina and on towards Greece. Rounding Cape Matapan, the southernmost point of the Mani Peninsula, in the early hours of November 21, the ship, with its complement of 1,066 souls, including crew, Royal Army Medical Corps personnel, and nurses, sped on to the Kea Channel, the narrow strait between Cape Sounion and the island of Kea.

At precisely 8:12 in the morning, a catastrophic explosion on its starboard (right) side sent a shock wave through the ship, causing panic and confusion onboard. Further aft, towards the back of the ship, crew and medical personnel thought they had simply hit a smaller vessel. Captain Bartlett and his officers on the Bridge, however, immediately knew the severity of the situation, and ordered the watertight doors shut and sent a distress signal. The hospital ship had hit a mine, lurking beneath the surface of the water. The ensuing explosion had already caused more damage to the hull than the iceberg that sank the Titanic. (It later transpired that the mine had been laid a month earlier by the German submarine SM U-73, commanded by Gustav Sieß).

As the first four watertight compartments were taking on water, Bartlett ordered his crew to prepare the lifeboats. Within one hour, the nearly 270m-long ship would be lying on her starboard side of seabed, with the loss of 30 lives.

A depiction of the Britannic's sinking, in the morning of November 21, 1916.

© Public domain

Maritime historians argue that the Britannic, which was well prepared for all eventualities, may have avoided sinking had it not been for two fatal mistakes.

Captain Bartlett made the desperate decision to steer towards the island of Kea, in the hope of grounding the ship in shallow water. This maneuver would have been successful had not the ship’s medical personnel opened the portholes on the lower decks to ventilate the patients’ wards. As the ship gathered speed, and listed more and more to starboard, water continued to flood through the open portholes.

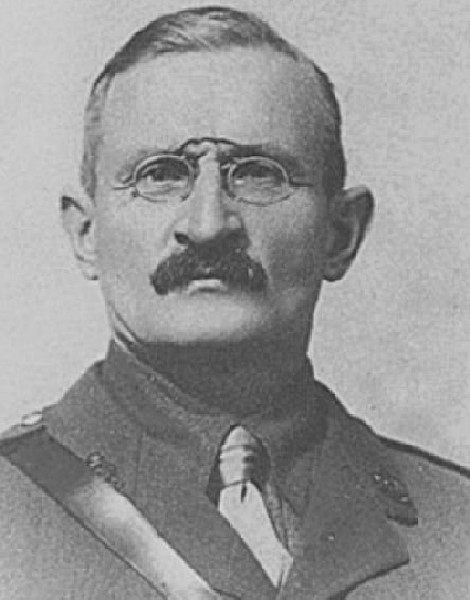

The tragedy intensified when, in confusion, crew members on the upper deck attempted to lower lifeboats without being instructed. As they were being lowered, two boats on the port (left) side were torn apart by the propellers and those on board killed, including Captain John Cooper, of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC).

Captain John Cropper of the RAMC, who died in the sinking.

© Public domain

Violet Jessop in her Voluntary Aid Detachment uniform while assigned to HMHS Britannic. She survived the sinking of both the Britannic and its sister ship, the Titanic.

© Public domain

By 08:50am, less than 40 minutes after the explosion, most onboard had successfully escaped in the 35 successfully launched lifeboats, including 29-year-old British Red Cross stewardess Violet Constance Jessop, who had survived the sinking of the Titanic four and a half years earlier. At 9:07, the Britannic finally sank beneath the waves.

Jessop described the ship’s final moments:

“She dipped her head a little, then a little lower and still lower. All the deck machinery fell into the sea like a child’s toys. Then she took a fearful plunge, her stern rearing hundreds of feet into the air until with a final roar, she disappeared into the depths, the noise of her going resounding through the water with undreamt-of violence….”

Fishermen from Kea helped about 150 of the survivors, picking them up with their caique and giving them first aid on the island, while two British ships, HMS Scourge and HMS Heroic, also came to their aid, picking up a further 833 people. In total, of the 1,066 people on board, only 30 died, infinitely less than the losses of the Titanic.

The HMHS Britannic was the largest ship lost during World War I.

Survivors of the Britannic on board HMS Scourge.

© Public domain

The wreck of the Britannic was discovered off the north coast of Kea in 1975 by the famous French oceanographer Jacques-Yves Cousteau (1910-1997), at a depth of 122m. Cousteau and his team discovered the giant wreck lying on its starboard side, hiding the section of the hull destroyed by the mine.

In 1995, Robert Ballard, best known for discovering the wreck of the Titanic in 1985, visited the site of the Britannic, obtaining images by using advanced side-scan sonar and other underwater remotely controlled vehicles (ROVs).

In 1996, the wreck was purchased by maritime historian Simon Mills, who has written extensively on the ship, including two books: “Britannic – The Last Titan” and “Hostage to Fortune.”

Nevertheless, as the wreck lies with the territorial limits of Greece, its protection as an archaeological site and as a war memorial is the exclusive preserve of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture. As a deep-water site, any divers with the necessary level of experience and equipment wishing to visit the wreck, must first seek permission from the Ministry’s Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities.

The HMHS Britannic remains the world’s largest sunken passenger ship.

Just an hour from Athens, Kea...