Ancient Pollution: How Greece’s Past Speaks to Our...

Think environmental pollution is a modern...

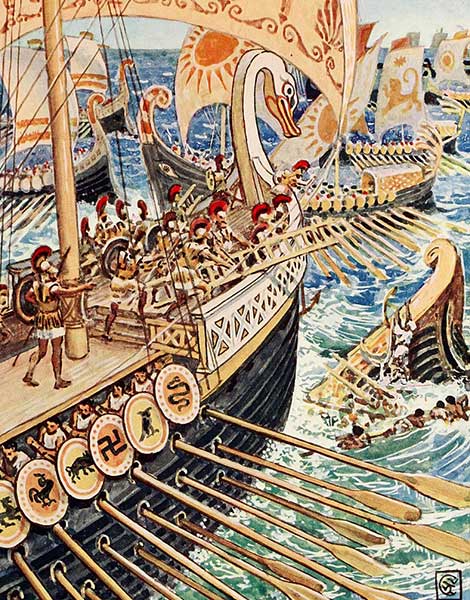

A romantic style painting of the Battle of Salamis, by artist Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1868).

As the early morning mist gently lifted from the sea, the young rower gazed out across the waterline in the direction of the oncoming ships of the Persian fleet, their oars sweeping up and down like giant wooden millipedes; fearsome looking millipedes with bronze-tipped battering rams.

Taking a deep breath and stealing his nerves, he looked around at his fellow rowers deep in the bowels of their large wooden warship, a trireme. Despite their limited time training together, the 170-man crew, arranged in three banks, had bonded well and, like all brothers-in-arms, found solace in a constant stream of playful banter.

By the mercy of the gods, he had just become a father to a beautiful baby girl, Myrtis. With thoughts of family and home at the forefront of his mind, he knew what was at stake if they failed that day. He knew what we was fighting for. They all did.

Now, in the line of battle, the older, more experienced men, some of whom saw battle 10 years earlier at Marathon, ushered words of encouragement to their younger colleagues.

Suddenly, in a cacophony of noise, sailors and hoplites on the top deck rallied to their stations, trierarchs and boatswains barked their orders, and the rowers of the combined Greek fleet braced for action.

Persian soldier (left) and Greek hoplite (right) depicted fighting, on an ancient kylix, 5th century BC. National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

Fought on the 28th or 29th September 480 BC, the naval Battle of Salamis was a turning point in the decades-long Persian Wars (499-449 BC), waged between the Achaemenid Persian empire and the city-states of Greece. Some historians have argued that is was the most significant battle in human history. Indeed, if the Persians had been victorious and pressed on with their planned invasion of mainland Greece, Western Civilization as we know it may have been very different.

Writing in the mid-5th century BC, Herodotus, regarded as the “Father of History,” is the main source on the period of the Persian Wars. Other sources provide complimentary insight, including the famous play “Persians” by Athenian playwright and tragedian, Aeschylus, who fought at Marathon (490 BC), Salamis (480) and Plataea (479).

The Battle of Marathon was the first major clash between the rival powers on Greek soil – the first Persian invasion under the reign of king Darius the Great. Newly-democratic Athens and their loyal Plataean allies scored a decisive victory against overwhelming odds, reinforcing the idea that an army of free citizen-soldiers (hoplites) fighting for their homeland was the ultimate defence against a powerful albeit largely coerced Persian force.

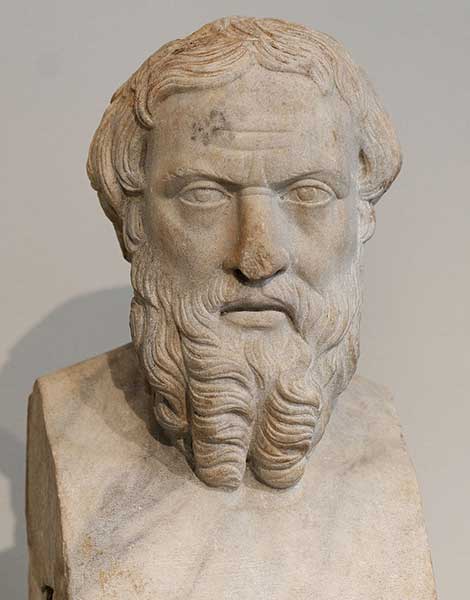

Herodotus, the main historical source for the Greco-Persian Wars.

© Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons

Late 19th-century painting by John Steeple Davis, depicting combat during the Battle of Thermopylae.

Ten years later, in the summer of 480 BC, king Darius’ son and successor Xerxes, launched a second invasion, vowing revenge and total supremacy over the Greeks. At the legendary pass of Thermopylae (“Hot Gates”) on the east coast, a Persian army of anywhere between 70,000 and 300,000 men came face-to-face with a small force of 7,000 Spartan-led Greeks, under the command of the Spartan king Leonidas.

A shrewd tactician, Leonidas had carefully selected the narrow pass at Thermopylae to neutralise the huge numerical advantage of the Persians, forcing them along a 9 km-long trail that never widened more than 20 meters. The sheer bravery, discipline and skill of the Spartan hoplites and their Theban and Thespian allies brought the Persians to a grinding standstill for two days. On the third, the traitor Ephialtes, a local man, betrayed his countrymen by revealing to the Persians a trail that circumvented the pass.

The sacrifice at Thermopylae, immortalised in Herodotus, nevertheless bought valuable time for the rest of Greece. In a fit of rage, Xerxes had Leonidas’ body decapitated and crucified, and rallied his army to march on Athens.

A sluicing tank for silver ore, excavated at Lavrion, Attica.

© Heinz Schmitz

In the aftermath of the victory at Marathon in 490 BC, there were many who felt the Persians remained a serious threat to the Greek mainland. Chief among these was Themistocles, the leader of the democratic faction in Athens who envisioned turning his city-state into a mighty naval power.

By lucky coincidence, in 483-482 BC, in the region of Lavrion on the southern tip of Attica, a rich vein of silver was discovered. The subsequent mines belonged to the Athenian state and proposals were put forward in the Assembly as to how to distribute the wealth. Some argued that 10 drachmas should be given to each citizen, while Themistocles suggested the city should invest part of the money in building more warships for the Athenian fleet – triremes – and training a force of citizen rowers to crew them.

Themistocles’ proposal was accepted and the Naval Law – the Decree of Themistocles – was passed. Over the next three years, the Athenian fleet doubled in size to 200 triremes, transforming it into the largest naval power in Greece.

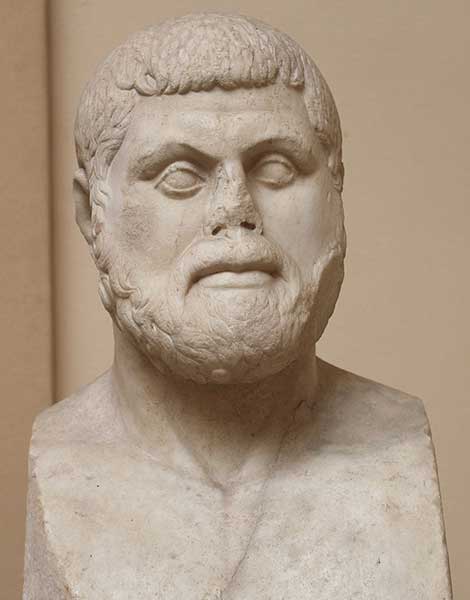

A Roman-era bust of Themistocles in "Severe style," based on a Greek original, in the Museo Archeologico Ostiense, Ostia, Rome, Italy.

© Sailko

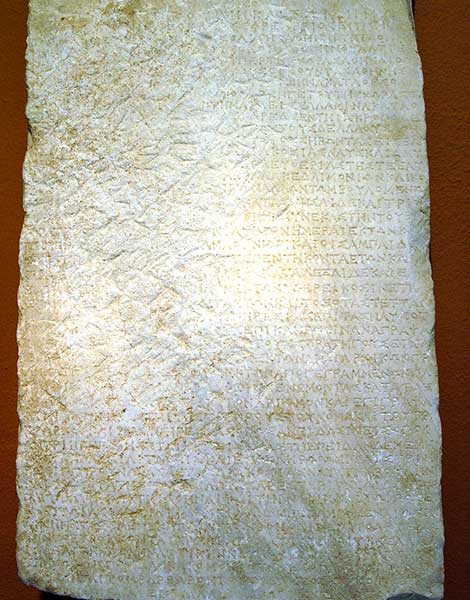

Decree of Themistocles, National Archaeological Museum of Athens, 13330

After Thermopylae, the Persian army and their accompanying fleet headed south, looting and razing towns and cities in their path, inlcuding Thespies and Plataea in Boeotia, and the sacred Acropolis of Athens.

As the Greek allies debated their best course of action, Themistocles made the case for assembling a combined fleet in the narrow strait of Salamis – a move reminiscent of Leonidas’ strategy at Thermopylae. The numerically superior Persians would again be neutralized in a restricted space.

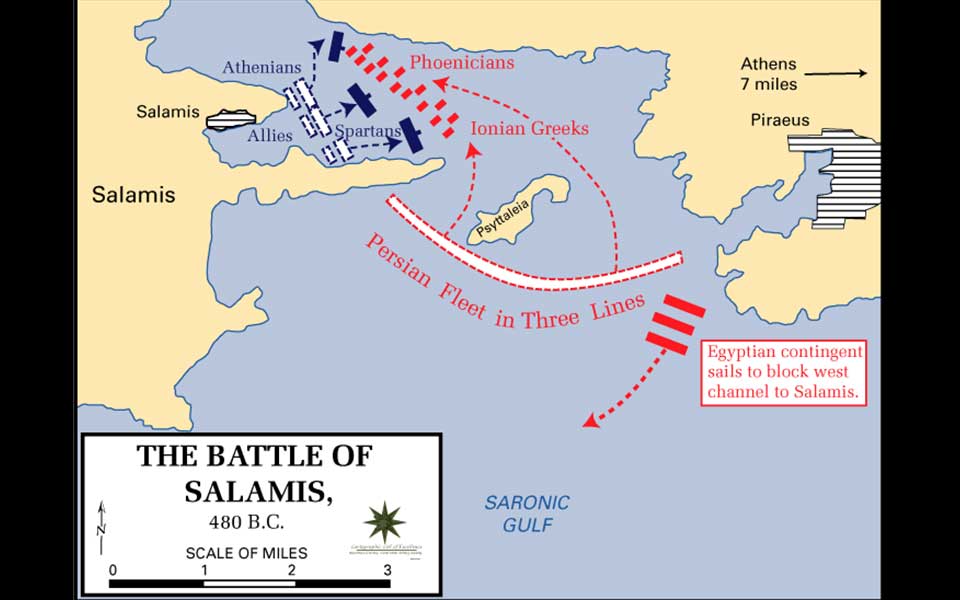

Battle order. The Achaemenid fleet (in red) entered from the east (right) and confronted the Greek fleet (in blue) within the confines of the strait.

© The Department of History, United States Military Academy

Herodotus reports that the combined Greek fleet, under the leadership of the Athenians, numbered 378 triremes, while the Persians had over 1,000. The Persians preferred to do battle in open sea, utilizing their numbers and lighter, faster and more manoeuvrable ships, but every detail had been calculated by Themistocles. The morning breeze made the Persian ships unstable in open water, forcing them to take the bait and advance on the narrow strait.

According to Aeschylus, who actually fought in the battle, the approaching Persians could hear the Greeks singing their battle (paean) hymn:

“On, you sons of Hellenes!

Free your native land. Free your children,

your wives, the temples of your fathers’ gods,

and the tombs of your ancestors.

Now you are fighting for all you have.”

Death of the Persian admiral Ariabignes (a brother of Xerxes) early in the battle; illustration from Plutarch's Lives for Boys and Girls c. 1910.

The Battle of Salamis, 19th century illustration.

The masterful tactic worked. The two fleets fought with an equal number of ships on the front line, with the elite crews of the Athenian triremes in the thick of the fight.

Armed with bronze-tipped rams, the ships rowed towards each other in full fury. The narrow strait made difficult to use a manoeuvre known as diekplous, rowing into the gaps between enemy lines, circling around and ramming the sides of the opponents ships.

Instead, after hours of close quarter combat, including archers and marines on the top decks boarding enemy ships and essentially turning the melee into a land battle, a wedge of Greek ships managed to force its way through the Persian centre, splitting the fleet in two.

© The Department of History, United States Military Academy

With momentum all lost, the scattered Persian squadrons went into full retreat. All the while, king Xerxes had been sat atop Mount Aigaleo on his throne, watching the carnage unfold.

Following the battle, Greek sea patrols forced Xerxes to abandon Attica. His dreams of total victory lay in shatters.

Crewed by well-trained and highly-skilled citizen rowers, the strategic use of the trireme was key to the Greek victory at Salamis. Earlier versions of the ship had been first developed by the Corinthians as early as the 8th century BC (from penteconters and biremes), but it was the Athenians who experimented with new tactics and manoeuvres, becoming, as Themistocles had hoped, the premier naval power in Greece.

© Shutterstock

The trireme was a light, fast, and highly agile ship. Armed with a bronze ram on the bow, its three rows of rowers (eretae) could propel the ship at speeds of 8 knots, essentially turning it into a giant seaborne battering ram. Triremes could sink enemy ships by ramming them, striking them on the beam, or skilfully manoeuvering to shear off the banks of oars on one side.

The command of the ship lay with the trierarch (captain), who part-funded the cost of building and maintaining it. The boatswain coordinated the 170 rowers in three rows below deck: the thranitae on the highest row, the zygitae on the middle, and the thalamitae on the lowest. On deck, sailors (to man the sails), archers and hoplites made up the rest of the crew.

In total, the crew of a trireme was around 200 – almost all would have been free citizens, paid by the state.

Fleet of triremes made up of photographs of the modern full-sized replica Olympias.

© EDSITEment

Monument for the Battle of Salamis, Kynosoura peninsula, Salamis Island, Greece, by sculptor Achilleas Vasileiou.

© Shutterstock

The victories of the Athenians at Marathon in 490 BC and ten years later at Salamis did two things: it dispelled the myth that the Persians were invincible, and it consolidated the future of Athenian democracy.

Alongside Sparta, the premier land army in Greece, Athens evolved into a powerful military force in its own right. The building of the war fleet, a stroke of genius on the part of Themistocles, ensured the city would play the leading role in the Delian League, founded in 478 BC, and become the most powerful maritime state in the Aegean.

Most important of all, the Battle of Salamis had strong repercussions on its own citizens. The glorious victory reinforced the political power of its lower class citizens – in terms of income – the thetae who manned the ships as rowers. Ultimately, their decisive role in the defence of Greece marked the supremacy of the values of freedom and democracy against tyranny and despotism.

Think environmental pollution is a modern...

A monument of memory and music,...

In 30 BC, Octavian, the future...

Lost to earthquakes, swallowed by the...