Walking Through Athens: A Cultural Journey Beyond the...

From historic landmarks to edgy street...

© Nikos Pilos

School’s out for the summer on the Askyfou Plateau. It’s a warm afternoon, and the children are playing in the streets – riding bikes, kicking a ball around or playing games, a lot of games, on their cell phones.

In the Ammoudari neighborhood, I come across two boys outside a workshop that still makes stivania – traditional Cretan boots. They’re playing with guns, or rather with well-made replica pistols. Each boy has two or three of them. They tuck them into their trousers at the waist, concealing them under their shirts. Whipping them out suddenly, they pretend to fire a volley of shots, laughing wildly as they spout the names of different guns.

With smiles on their chubby faces, they’re just two ordinary children playing with toy guns, like anywhere else in the world. But still, it’s difficult to ignore the fact that I’m in the place with the highest rate of gun ownership in Greece.

“I hope it wasn’t you who made all those bullet holes in the road signs of Sfakia,” I tease one of them. “No, these aren’t real guns,” he replies, quite seriously. “Are you ‘playing’?” I ask the other, which, in the local dialect, means firing real bullets into the air or at some inanimate object. He laughs. “No, we’re not ‘playing’,” he replies. “Only grown-ups do that.”

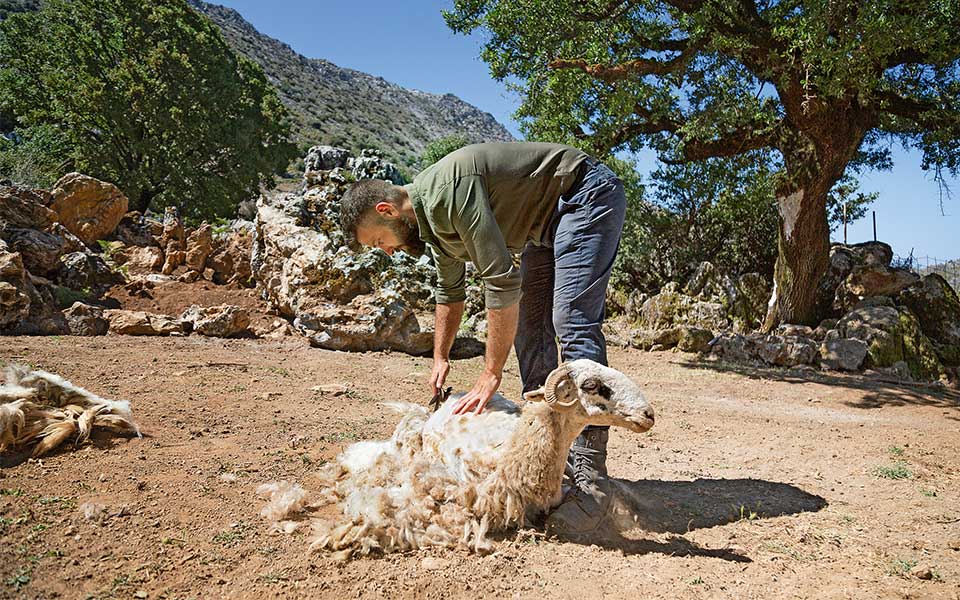

Young Sifis Manousakas is shearing one of his sheep at the family mitato.

“They can kill each other over a sheep,” the other boy says, provoking an immediate reprimand from the bootmaker inside, who barks: “We don’t speak about these things!”

It isn’t easy to get a Sfakian to speak about “their things,” the set of unwritten laws that govern family and social relationships and which have been passed down from one generation to the next. They won’t speak openly about the livestock rustling or the blood feuds that still keep people vigilant. You won’t be told which families are in conflict with each other or for what reason, but you will hear discussions about what constitutes tradition.

A few steps away, in the neighborhood kafeneio (coffee house), Nektarios tells me about perceptions, misperceptions and the state of confusion among the younger generation regarding what such things mean. He talks about the black shirts and moustaches worn by many men; the former was originally an expression of mourning, but which later became a local fashion.

He speaks about the rifle, once a family heirloom, a symbol of honor, but which is now used to demonstrate one’s “manliness” by shooting at signs or into the air at social events. He talks about livestock rustling which, during the time of foreign occupation, was seen as an act of bravery, but which is now simply a source of conflict between neighbors.

“Sfakia is synonymous with stories of heroism,” Nektarios says, “and the legacy of that heroism weighs heavily on people today; they’re trying to emulate their forefathers.”

The fertile Askyfou Plateau, as seen from the mountains above.

© Nikos Pilos

Nobody needs a map to know when they’re in Sfakia. Driving from Hania, I realized as soon as I reached the Krapi Plateau that this is the gateway, a natural passageway, to another world, a world of mountains. Up here, in the Katre Gorge, Cretan rebels fought fierce battles with Ottoman forces to prevent them from entering Sfakia. It’s up here, in these highlands, that the history of a fearless and unyielding Crete was written.

Today, I’m driving east towards Kallikratis, through a landscape that’s remained undisturbed since those battles were fought. It’s a stony land. The sunshine is relentless, and it’s still only eight in the morning. Sheep and goats vie for a place in the shade next to the roadside barriers or huddle together motionless under a lone tree.

Made up of four widely-separated neighborhoods, the village of Kallikratis is nestled among trees. There are almost as many coffee houses as residents. In front of one of them, I meet 87-year-old Nikitas Manouselis leaning over a large vat, stirring fresh milk with a very old wooden paddle in order to make the last graviera cheese of the season.

As we chat, he takes me back to 1943, and more specifically to October 8th, when German troops entered the village. He describes his every movement; how he snuck out of the village with another child his age; how they spent the first night in a cave; how, when returning, they bumped into some Cretan collaborators who shot at and chased them; and how he was fortunate to escape. He pauses, and then tells me about the moment when his father, after a fierce hand-to-hand fight, was murdered by a collaborator. In the space of four months, 31 people lost their lives; their houses were looted and burned. Most still stand in ruins today, harrowing reminders of the tragedy that befell the village.

Road signs in Sfakia are often used for target practice by the locals.

© Nikos Pilos

Like all shepherds in Sfakia, Manouselis moves around a lot. In the winter, you’ll find him down on the plain of Frangokastello, but in summer he takes his flock up to Kallikratis, from where he will ascend to the mandares, the high mountain pastures. In the past, the women and children would remain in the village and the men would make their way up to one of the dry-stone shelters known as mitata. But now, pastoral life has changed. The mountain paths have been replaced by roads, and what used to be a long slog on foot is now a short, pleasant drive in a 4×4.

“The conveniences of modern life have changed everything,” says 27-year-old Sifis Manousakas as he drives us up to his mitato above Kallikratis in his jeep. A member of a well-respected and affluent family of local shepherds, he speaks with the confidence of an educated man who has traveled widely. Market distortions in the livestock sector, he says, have pushed many shepherds to the brink of poverty. Many have reached the point where they no longer milk their animals because the price of milk is so low. Wool has lost its value, and even the meat is sold for a pittance. Sifis believes that improvement will come only from tourism. He hopes one day to partner with an international travel agency and turn his mitato into a place to visit.

There’s no question of leaving Kallikratis without visiting Sifis’ home; it’s simply not an option. I’m greeted with Greek coffee and cookies, braided gamokouloura (wedding bread) and graviera cheese, and traditional cheese pies drizzled with honey. They’re on the table, served by Sifis’ mother, Pagona, and his sister, Asimenia, even before I sit down. It strikes me that these are the first women I have met here.

“Sfakia appears to be a world of men,” I remark, a statement which seems to puzzle them. These are clearly strong women; they’ve simply become accustomed to staying in the background. Sifis’ elderly father, who is also called Sifis, speaks to us about the history of the place, a history that’s not written anywhere and not taught in any school. But his children listen attentively, knowing they’ll soon be passing it on to their children. Asimenia shoos the flies that have taken a keen interest in the delicacies spread out before us. Before leaving the table, we have to finish all the food… even if we’re already quite full. Sfakian hospitality, while exemplary, can sometimes border on the onerous.

Nikitas Manouselis is busy making cheese in the village of Kallikratis.

© Nikos Pilos

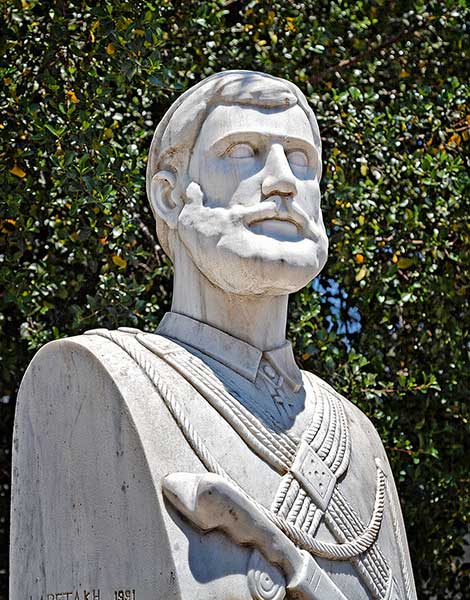

In Sfakia, the most revered hero is Daskalogiannis. Instigator of the 1770 revolt against Ottoman rule in the region, his limited forces were defeated by superior Turkish numbers, and he was tortured to death. In the shadow of his bust in the center of Anopoli, the village where he was born, we watch as local men, dressed in traditional attire, perform a rizitiko song and then dance the customary pentozali in honor of their hero.

“It’s our duty to be ready to fight, with allies or without, just as our heroes did. We must be prepared to follow their example,” says one of the dancers, 27-year-old Giannis Magelakis.

How could it be otherwise? You’d be hard pressed to find a village that doesn’t boast the bust of at least one Sfakian hero, or hear a tale from the past that didn’t include a reference to war, or enter a house in which there are no firearms. As I approach the Lefka Ori (“White Mountains”), just before the Aradena Gorge, I recall those boys playing with replica guns. In such a dramatic natural landscape, very little imagination would be needed to see yourself as a warrior on a battlefield. In all the great uprisings in the region, the final important battle took place here, at the entrance to this gorge, in order to safeguard the women and children who had sought refuge in the mountains by preventing the enemy from reaching the villages on the other side.

The men of Sfakia are proud of the legacy of heroism and resistance left to them by their ancestors.

© Nikos Pilos

© Nikos Pilos

One of these villages is Ai Giannis. Known in Greece as the hometown of the Vardinogiannis family, among the country’s most prominent shipowners, it’s a humble village where electricity first arrived in 1985 and where it wasn’t until recently that a paved road was created.

It is also the location of the Alonia guesthouse, whose owner, Antonis Georgedakis, is busy organizing a contemporary revolution of his own, a heroic act of resistance against the mass tourism threatening the stronghold of Sfakia. At his guesthouse, which began as a refuge run by his father for hikers in the White Mountains, you’ll find simple but pleasing accommodations and home-cooked Cretan food.

Antonis has a vision for Sfakia. He wants to preserve the natural mountain terrain, mark out more of the walking paths, and retain livestock farming but on a smaller scale, without reliance on subsidies. And in Sfakia’s tourist areas of Loutro, Hora Sfakion and Frangokastello, he wants to see greater emphasis on local cuisine and no further seafront development. More than anything, he wants to see a collective effort to achieve these goals.

These are the battles that will be fought in the coming years as Sfakia increasingly opens up to tourism, battles that will be fought without guns, but that will demand the same courage and sense of duty that the locals have always displayed. The question is: will the Sfakians defend Cretan graviera, local goat meat and Askyfou potatoes, or will they succumb to Danish feta, New Zealand lamb and Dutch tomatoes?

From historic landmarks to edgy street...

Landmark shops, a lively cultural scene...

Discover how ancient Greek architecture inspired...

With fewer tourists, sunlit harbors, and...