Let’s go back in time a bit – to Crete in 1930 – to a village in the Sfakia highlands in the northwest of the island. There’s been a wedding and the party (the glendi or glendia in the plural) is in full swing and shows no sign of winding down, as the hours turn into days. Two bleary-eyed musicians struggle to stay awake and yet continue to play: for two days, three days, four days… a week. A few people are dancing, some are singing, others are pouring out wine and passing around platters of roasted goat. Further away, others still are getting a spot of sleep; soon they will wake up to do it all again. This is what a Cretan village looks like in festive mode.

I was fortunate enough to meet almost all of the leading protagonists of Crete’s legendary glendia, those musicians who left such an indelible mark on the island’s heritage of music and dance. The words of two very prominent musicians – Iraklis Stavroulakis, an incredible fiddle player from the village of Episkopi in Irakleio, and the multi-instrumentalist and composer Stelios Foustalieris, from Rethymno – who spoke to me in the mid-1980s are especially memorable. Both died a few years later.

Iraklis Stavroulakis: “Back in the day, people would look for any excuse for a party – on the feast days of small churches, at the kafeneio (coffee house), at people’s houses, anywhere. There was no electricity, of course. They’d place two lyra players on two chairs in the middle of a space, gather around them, and the dancing would begin. Starting the party was easy; ending it was the hard part…”

Stelios Foustalieris: “Glendia used to go on for days everywhere, but in Sfakia they really seemed endless. They could go on day and night for as long as a fortnight. Our fingers would swell up, our nails would tear, our hands would be bloody. But we played. I fell asleep a few times while playing my boulgari and the lyra player beside me would give me a nudge to wake me up. It was an unwritten rule that the party should never stop. By the end, I’d have blisters and welts under my arms…”

© Dimitris Vlaikos

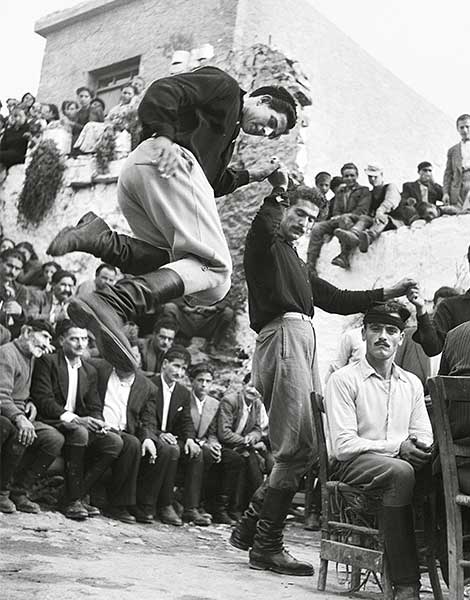

These things don’t happen anymore, but they are indicative of just how important the glendi – a word which describes both an event and a state of mind – is to the Cretans. We have ancient references to men dancing in full battle gear and accounts of such festivities taking place even in tough times like the Nazi occupation, of dancing that expressed the brutality of war together with the tenderness of love.

The Cretan glendi is linked to the past, but it’s also all about having joy in the present. This is why some of the most iconic dances performed on these occasions evoke such passion and intensity – dances like the pentozali or the maleviziotis, also known as the pidichtos in some parts of the island. Even now, when dance schools have, to a large extent, become the guardians of Crete’s heritage, imposing a uniformity on these arts that is not part of their natural character, the island’s traditional dances continue to constitute a colorful mosaic that lacks nothing of the force, passion and joie de vivre of yesteryear. The pentozali, one of the most popular and also most dynamic of the dances, is said to stem from the ancient Greek Pyrrhic War dance. Another dance that also appears to have the same origins is the sousta, the intensity and rhythm of which evokes something almost erotic that speaks to the dominant role of women in Cretan customs.

If you’re very lucky, you might find yourself at a genuine village party, one that doesn’t have microphones, hasn’t been organized, and doesn’t feature formal dance moves like those we see at tourist events. All you need is two or more musicians to start off the singing with a mantinada, a native form of poetry consisting of short verses with rhyming couplets that tell a full story. Everyone sings, not just the musicians. Every so often, a mantinada may evoke a response from another reveler, sparking a “conversation” in sung verse. And, of course, someone is almost certain to get on their feet and dance.

© Dimitris Vlaikos

The people of western Crete have their own kind of glendi and often don’t even need a musician to get things going. It usually starts at a long table, laden with meats, cheeses, breads and pies, where a gathering of friends will drink and talk, inspiring a guest to start singing, usually in thanks to the host and hostess: “I revel in your valued company / worthy and wise…” sings one member of the party, as others repeat the verse and answer with a second. These non-rhyming songs are called rizitika and are deeply rooted in the Cretan soul, dating back to Byzantine times. They may inspire dancing or they may not. The people here have their own type of glendi which may go beyond just singing and dancing. It’s basically about camaraderie, about the sentiment it evokes. “I felt such a frisson, I got up on my own and started to dance,” says my friend Eftychis of one of his experiences; today he’s a member of a group that is dedicated to preserving the authenticity of the rizitika.

While it’s rare in this day and age to find these more spontaneous celebrations, it’s certainly worth trying to attend an organized Cretan glendi, whether in the square of some remote village, at an event organized by a cultural association or, better yet, at a panigiri (usually a celebration of a church’s or village’s patron saint). At these gatherings, the glendi is an element of the local identity, with older residents passing the torch onto the young. The village ovens are put to work days ahead, as every Cretan glendi is also about flavors and aromas – a feast of local culinary delights, which often involves villagers bringing huge pots and trays of food that they have cooked at home to the main square to share with everyone else.

© Thalia Galanopoulou

© Dimitris Charissiadis/Benaki Museum Photographic Archives

I once found myself in a village in Sitia, to the east, called Tourtouli (or Aghios Georgios), in the company of good friends who hailed from these parts. The square filled up within minutes as locals came out to greet them. Then all these platters started to come out of people’s homes, laden with all sorts of treats that included the family’s food for the day and pies that had made for the occasion. A lyra started to play and the musicians started to sing. The people in the square joined in with mantinades, either “gnomikes,” meaning they imparted a piece of wisdom, or “erotikes,” romantic verses, songs full of feeling. It was then that I realized that these people weren’t just singing for the sake of their friends; they were filling their own souls with music. The party went on into the small hours, even though it was August and the villagers had to be in their vineyards very early to harvest the grapes. I had a similar experience earlier this year in the town of Sitia, where I’d been invited to speak about my new book. My friends had booked an entire taverna for the after-party. The strum of a single lute was enough to get things going! And so many mantinades! Everyone sang, as though passing the baton from one to another. In the middle was an amazing poet called Manolis Miaoudakis, who had been asked to read his latest satirical poem. Within minutes, the eroticism of a mantinada had given way to Aristophanic proclamation. How we laughed! We laughed non-stop. The wine flowed non-stop, too, courtesy of a winemaker friend who had bottled some specially for the occasion, with labels reading that the wine was not for sale, and was only to be given as a gift. I’ve kept one of those bottles as a memento.

It really doesn’t take much to get a Cretan glendi going. A visit from a good group of friends, a name day or the return of a relative from distant parts are the most frequent excuses for smaller-scale family parties, while weddings, engagements, baptisms and other important social occasions usually call for bigger, more organized festivities.

© Thalia Galanopoulou

The church festivals (panigiria in the plural) are special occasions, and something that those who have moved away from their villages really miss. Local religious celebrations often end up in a glendi and, in older days, several parties would be set up in every village during the panigiri as all the eateries would invite groups of musicians to perform. Today, gatherings like these are organized by local cultural societies as well, and are no longer limited to events on the Greek Orthodox calendar. Some are organized to promote a local product or custom, or some other element of the area’s identity, so we have multiple festivals throughout the year: for snails, for shepherds, for cheese and for potatoes, for example. Last year, in early August, I found myself in Kastamonitsa, a village 40 kilometers from Irakleio, for the Eftazymo Festival. Eftazymo (derived from aftozymo, or “self-rising”) is the area’s traditional bread and the ovens in the village had been turning out hundreds of loaves of the stuff for days; some were being given out to guests, others were for sale.

Decked out in all its finery, the village looked like a museum of traditional crafts, as the local women had lined the streets with beautiful rugs and fabrics they had woven or embroidered by hand. The “glendi” started in the schoolyard as soon as the sun went down, but this venue was just too small to accommodate the thousands of locals and foreign guests who’d come to join in.

On the rare occasions when social events others might consider private, such as wedding or baptism feasts, are held in the village square, outsiders are always welcome. No one is allowed to pass by without being treated to a plate of food and a drink. It is, to me, evidence of the innate Cretan sense of hospitality. It’s also quite common to see locals dragging some foreign visitor along to teach them the steps of a dance. This kind of public, grassroots party has, unfortunately, almost disappeared, as such celebrations have been moved into huge events venues that have appeared all over the island. Today, these are often where weddings and baptisms are held. They can accommodate hundreds of people and may even have a chapel on the grounds for the religious component of the event.

Other changes have also had an immense impact on the character of the glendi. It has, for one thing, largely lost its polyphony, as now only the musicians sing, and they use modern electrical equipment set at such volumes as to be jarring. Nonetheless, the three-stringed Cretan lyra is still the star instrument, though the fiddle is more prevalent in some parts, like eastern rural areas for example, with the lute and mandolin treated as backing instruments and the askomantoura (called the tsambouna or askavlos in ancient times), a bagpipe made from a goat’s skin, adding its own special note to the island’s musical heritage.

In many cases, the glendi may have lost certain elements of authenticity. At times, it may appear to be a hollow reconstruction of older customs, or overly influenced by modern urban-style festivities, but it is still a fundamental expression of the traditional communities and the way of life of Crete. It gives deeper meaning to notions of tradition and harkens back to the roots of a culture which has suffered war and occupation, but which never once stopped celebrating the joy of life.

© Illustration: Anna Tzortzi

© Illustration: Anna Tzortzi

CRETAN DRESS

- vrah-kah: Pantaloons introduced by pirates, made of dark blue felt-like fabric.

- kah-poh-to: A short, ornately embroidered cape with a hood, worn loosely over the shoulders.

- poo-kah-mee-so: A shirt, white for weddings and other festive occasions and black when the wearer is in mourning.

- my-ee-dha-knee: A short, red-lined felt jacket with tight sleeves worn on top of the shirt.

- yea-leh-key: A sleeveless vest that fastens in the front.

- zoh-knee: A belt made of fine wool or pure silk, with a length of approx. 8m and a width of 50cm.

- sah-ree-key: A black silk headscarf with a thick, tasseled fringe (which is said to symbolize the tears of the once enslaved Cretan people).

- ah-see-mow-mah-hair-row: A dagger, the only one in the world with a V-shaped hilt, with a sharply pointed steel blade.

- kah-dhe-nah: A man’s necklace, the only piece of jewelry in the traditional male costume, often attached to a pocket watch.

- stee-vah-nya: Knee-high leather boots

MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS

- lee-rah (Lyra): this is a three-stringed pear-shaped instrument, of which there are three types (distinguished by shape, sound and use).

- lah-oo-toe (Cretan lute): it accompanies the lyre in rhythm and harmony, though it’s often used as a solo instrument as well.

- man-doh-lee-no (Mandolin): this is an instrument with European roots that’s mainly played solo.

- vee-oh-lee (Fiddle): a traditional folk instrument in Crete, the fiddle helped shape much of the island’s music.

- as-koh-ban-doo-rah (Cretan bagpipes): important in setting the mood for dancing, this instrument is made from the entire skin of a small goat, and has wooden components as well.

- dah-oo-lie-key (Small drum): it’s played with two drumsticks and always accompanied by at least one melodic instrument, such as the Cretan bagpipes, lyra or fiddle.

- bool-gah-ree (Long-necked lute): the bass chord of this three-stringed lute delivers a distinctive sound.

- sfee-roh-hah-bee-oh-lo (Cane flute): this flute is usually carved from one length of cane; it delivers a different tonality depending on its length and its internal diameter.