Why Now Is the Best Time to Discover...

Explore Ancient Messene, enjoy the local...

Temple of Athena: The Parthenon, visual centerpiece of the Athenian Acropolis, amid scattered architectural remains of shrines and dedications that once adorned the Sacred Rock.

© Shutterstock

On a late autumn day in 438 BC, as the sun neared the glistening sea on the horizon, Pheidias gently ran his fingers along the thick neck of the horse. He slowly traced the vertical lines of its taut musculature up towards the curving head and, with squinted eyes, smiled in satisfaction. It was a masterpiece of high-relief sculpture, made from white crystalline marble quarried from nearby Mount Pentelicus, just north of the city.

His skilled craftsmen, Alkamenes, Agorakritos and others, had done all of the initial work, carving out the relief and main features of the galloping animal and its young rider, but he, as the overseer (episkopos) and master sculptor, was there to add the finishing touches. Like all great artists, he was a stickler for detail. He wanted his craftsmen to create the impression that their sculptures could come alive at any given moment and step out of the frieze.

High up on the scaffolding on the western side of the cella, the inner chamber (naos) of the Parthenon temple, beams of soft light skipped over the deeply cut lines, curves and folds of the sculpted figures, catching the shadows and giving the impression of subtle movement.

Renowned for his colossal bronze statue of the goddess Athena Promachos (the “Defender”) that guarded the entrance to the sacred rock of the Acropolis, Pheidias, now 43 years old, walked along the marble frieze, surveying the rank and file of carved horsemen. Divided into ten ranks, they represented the ten tribes of Attica. Almost all the riders were depicted as beardless youths, dashing cavalrymen in the prime of life: a conscious display of the power and vitality of the great state of Athens, and a memorial to the brave Athenian warriors who had fallen in the Battle of Marathon against the Persians 52 years earlier.

A Cavalcade in Stone: Young cavalrymen taking part in the Panathenaic Procession, the annual celebration of the birthday of the birthday of the goddess Athena. Marble relief (Block XLII) from the north frieze of the Parthenon, on display in the British Museum.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

As the goat tallow torches flickered in the fading light, Pheidias and his craftsmen were busily finishing their Herculean task. Carved in situ around the four outer walls of the cella of the gigantic Parthenon, the largest and most impressive temple to Athena in the Greek world, the 160-meter-long sculpted frieze was close to completion.

Consisting of 378 figures and 245 animals, it told the story of the Panathenaic Procession, a religious event that took place in the city every year to commemorate the birth of the goddess. The planned sculptural decorations for the other parts of the temple – the pediments and metopes – would represent the usual fare of Olympian gods and scenes from myth and legend, but the figures on the frieze were different, quite unlike anything that had been done before.

Without a doubt, this was Pheidias’ masterstroke. He had overseen the creation of a unique artistic narrative that represented the Athenians themselves; not gods or heroes, but mortals, brave and audacious participants in the first great democracy.

Chariots of the Gods: Surviving sculptures from the east pediment of the Parthenon, portraying the heads of three horses from the chariot of Selene, goddess of the moon, descending through the bottom of the pediment.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Today, nearly 2,500 years later, the Parthenon stands as one of the most magnificent and best-known monuments in the world, a lasting reminder of the artistic and cultural achievements of the ancient Greeks, and a universal symbol of Western civilization.

Inscribed in 1987 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, along with the other monuments of the Acropolis, the building was originally adorned with hundreds of beautifully crafted sculptures, made entirely of locally sourced Pentelic marble. Conceived and sculpted between 447 and 432 BC under the watchful eye of Pheidias, the Parthenon sculptures were not intended as freestanding works of art. Instead, they functioned as an integral and highly symbolic part of the monument, depicting the founding stories of the city and people of ancient Athens.

For his overarching theme, Pheidias chose the eternal struggle between order and chaos, a powerful metaphor for the recent wars between the civilized Greeks and the barbarian Persians; a lengthy conflict, including the seismic battles of Marathon (490 BC) and Salamis (480 BC), from which the Athenian-led Greek forces had, against all odds, emerged victorious.

Following the end of the Persian Wars in 479 BC, Athens was the most powerful city state in Greece. A year later, it became the self-appointed head of a large tribute-paying confederacy that defended the Aegean against further Persian aggression. The Delian League, as it was known, originally kept its treasury on the sacred island of Delos in the heart of the Cyclades, but, in 454 BC, the Athenian Assembly had it transferred to Athens itself, to be kept on the Acropolis. It was a bold move; one that signaled the beginning of the Athenian maritime empire.

Pericles, a highly respected military leader and orator in the assembly, argued for revenue from the league’s treasury to be put aside for an immense building program on the Acropolis that would make the city the envy of the known world.

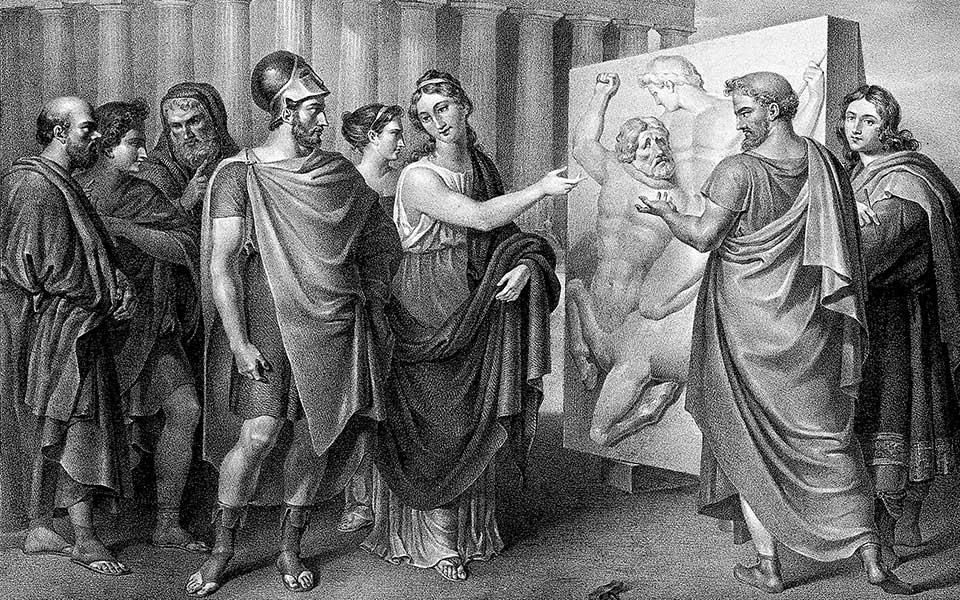

The Age of Pericles: Athenian statesman and general, Pericles (c. 495-429 BC) and his companion Aspasia, directing Pheidias’ work on the Parthenon sculptures. Pericles launched the monumental building program on the Acropolis in the mid-5th century BC.

© AFP/visualhellas.gr

The still-standing monuments of the Athenian Acropolis, including the Propylaea (monumental entrance way), the Temple of Athena Nike, and the Erechtheion, all built in the second half of the 5th century BC, are a testament to his great vision. This 50-year period, a golden age for ancient Athens, is commonly referred to as the Age of Pericles, and the Parthenon, with its richly carved sculptures, was its crowning glory.

The Temple of Athena Parthenos (the “Virgin”) – the Parthenon – chief temple of the goddess Athena, is a masterpiece of architectural design and engineering. Built between 447 and 438 BC by the great architects Iktinos and Callicrates, it became the center of religious life in the city and a powerful and enduring symbol of Athenian democracy. It was the largest and most lavishly decorated temple that mainland Greece had ever seen.

Pheidias’ once brightly painted sculptures atop the Parthenon’s forest of columns represented a high point in Classical Greek art. The restless swirl of figures not only commemorated the history and mythological foundations of the city of Athens, they were a glorious manifestation of democracy itself, with every finely carved figure a tribute to the primacy of the individual in this bold, new system of government – the first of its kind in the ancient world.

The Parthenon Marbles, In-Depth, Part 2: A Turbulent History

The Parthenon Marbles, In-Depth, Part 3: Abducted

The Parthenon Marbles, In-Depth, Part 4: The Campaign for Their Return

The Parthenon Marbles, In-Depth, Part 5: New Momentum (and What British Voters Can Do)

Explore Ancient Messene, enjoy the local...

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

A 3D reconstruction by Oxford researcher...

Whether drizzled on lentils, stirred into...