532 BC, 62nd OLYMPIAD

The Legendary Wrestler

It’s only been a few years since Milonas from Croton, then still a child, entered this very same sandpit and proved himself to his opponents – with startling ease – an Olympic wrestling champion. Today, a grown man, he has returned again and is thirsty for victory. The beefy Crotonian pinned every one of his opponents three times to the ground with little effort. Stories abound about his superhuman muscular strength. People say that if you tie a rope around his head, he can break it just with the force of his facial muscles. Or that to sustain his hulking body, he eats 5kg of meat and 5kg of bread every day! Truth or fiction, the sure thing is that at this moment there is no athlete in the world who can beat the speed and power of his hands, not even the Spartans, who triumphed in the last nine Games with Hipposthenis and Etoimoklis.

• Milonas, who won a total of six times at the Olympic Games, is considered one of the greatest athletes of the ancient world. His exploits made him a near-mythical figure.

• The pairing of opponents in heavy sports (wrestling, boxing, pankration) was determined by lot and contestants advanced to a final match as the defeated competitor in each round was eliminated.

• Athletes who won without falling, that is, with a 3:0 score, boasted that they had won “unfallen.”

• In heavy events there were no distinctions in weight between athletes.

512 BC, 67th OLYMPIAD

All-distance Runner

Fanas made it into the Pantheon today. The young athlete from neighboring Pellene won three running events in a row, reveling in the cheers of some 45,000 spectators who have come from all over the world to honor Zeus and take in the exciting competitions between top athletes. The young man excelled in the stadion race – covering the distance of 600 podes (Greek feet) faster than his opponents – and then ran twice that distance in the diaulus event, before triumphing in the dolichos, finishing first after 24 laps. His performance is clear proof that a fast runner can also have remarkable endurance. Fanas’ victory has put an end to the long winning streak by athletes from Croton, who have dominated the running events since the 48th Olympiad.

• 600 podes correspond to approximately 192m or one ancient stade.

• The start of running races was marked by a long stone pavement with two parallel grooves, on which the runners placed their feet, thus assuring a fair, equal starting position. Later, a taut horizontal rope began to be placed in front of the runners, which was dropped with a special mechanism triggered by the starting official.

• Athletes who won three running events in the same games were called “triastis.” Fanas was the first to achieve this feat.

• Leonidas of Rhodes was considered the top runner of the ancient world and the athlete with the greatest number of victories at the Olympic Games. He became a triastis at four consecutive Olympiads, from the 154th to 157th.

“The pairing of opponents in heavy sports (wrestling, boxing, pankration) was determined by lot and contestants advanced to a final match as the defeated competitor in each round was eliminated”

480 BC, 75th OLYMPIAD

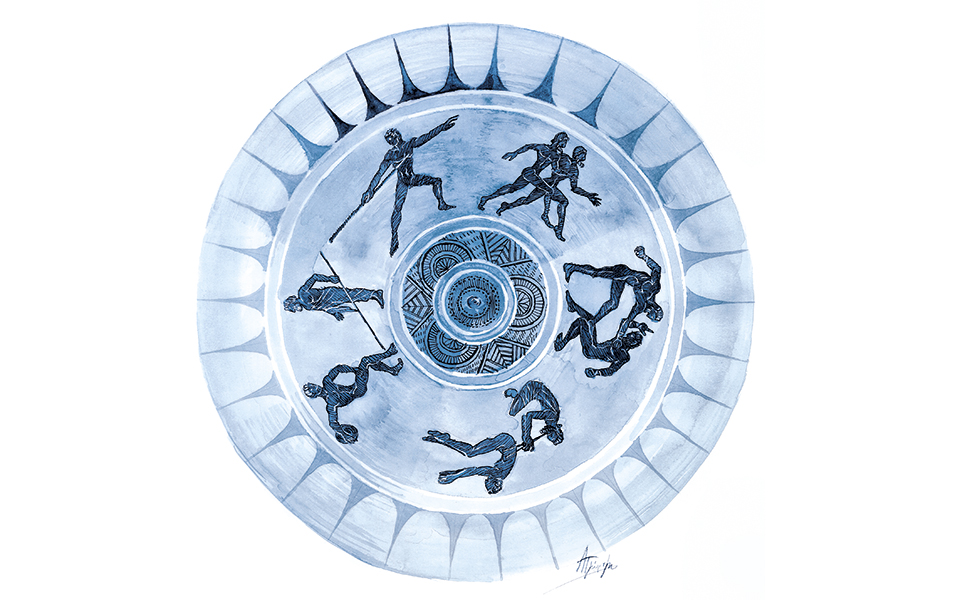

Pentathlon Exploits

Damaretos of Heraia was a great athlete in his youth, the victor in the 65th and 66th Olympic Games in the hoplite running race. Today, his son Theopompus demonstrated – in the same stadium in which his father competed – that he too has extraordinary talents. After all, who could challenge the sheer power of an athlete who managed for two consecutive Olympiads to triumph in the pentathlon, thereby proving he had speed, strength and endurance? Today’s competition started in the stadium with jumping, followed by the discus, javelin and running events, then ending with wrestling in the sandpit. Consecutive victories in the pentathlon have been recorded since the 28th Olympiad, as have the feats of the legendary Philombrotos of Sparta.

• Theopompus II, son of Theopompus and grandson of Damaretos, also became an Olympic champion, in 440 BC, in wrestling.

• Jumping took place from a still position, but with the help of two hand-held stone or lead jumping weights, weighing 1.5-2kg, which athletes thrust in front of their bodies at the moment of take-off. Their efforts were accompanied by music from a flute.

• The bronze or stone discuses had a diameter of 17-32cm and weighed 4-5kg. Each competitor was given five throws to achieve his best mark.

• The spear-like javelin was wooden and had a length of 1.5-2m. At the center-point of its weight a leather loop was tied, through which the thrower hooked two fingers, while his other three gripped the javelin. After he released the javelin, the athlete would yank the loop forward, thus giving his javelin greater momentum.

448 BC, 83rd OLYMPIAD

In the Name of the Father

After the two brothers Akousilaos and Damagetos were crowned with olive wreaths for their victories in boxing and the pankration, they ran wearing their wreaths to their father in the crowd and lifted him up on their shoulders! Their father was none other than the legendary Diagoras of Rhodes, the Olympic boxing champion from several years ago and a frequent victor in panhellenic games. None of his past accomplishments, however, gave him the same pleasure as he felt today with his sons – the joy of watching one’s children excel while also displaying great graciousness of character. Indeed, someone from the audience yelled out: “Time to die, Diagoras! You won’t climb any higher or reach Olympus!” Well said, because truly no moment of his life from hereon will top today.

• Dorieus, the third son of Diagoras, was also a famous boxer and pankratist, who won twice at Olympia in 432 BC and 428 BC. He won again in 424 BC, but this time on behalf of Thurii in southern Italy, where he had fled after being exiled by his political opponents.

• In the pankration, everything was allowed (headlocks, punches, kicking), but no biting or eye-gouging.

• The pankration ended only when one of the two competitors made a gesture with his finger to acknowledge his defeat.

• Although the pankration was the cruelest and most dangerous of all the events in ancient Greek athletics, fatal incidents or serious injury among pankratiasts were minimal, which is generally very commendable for an ancient sport.

“In the pankration, everything was allowed (for example, headlocks, punches, kicking), but no biting or eye-gouging.”

396 BC, 96th OLYMPIAD

The Female Touch

After centuries, this, the 96th Games, will go down in the history books not only for the achievements of the athletes, but also for the unprecedented number of women who attended! We have seen the brave Kallipateira defy a penalty of death by entering the stadium disguised as a trainer in order to revel in the sight of her son Peisirodos competing in wrestling. And while a second proud mother, Roditissa, similarly violated the sacred rules, another woman, Cynisca, followed the regulations precisely and became the first female Olympic champion! As a daughter of the Spartan King Archidamus II and sister of Agesilaus II, Cynisca invested her wealth in buying chariots and horse breeding, before hiring a skilled charioteer that managed to win the chariot race. Her two-wheeled chariot with four powerful horses was the first to finish the 12-lap race.

• The four-horse chariot race was introduced in 680 BC. By 256 BC, seven other equestrian events had also been gradually added, classified by the horses’ age and sex, as well as by the kind of chariots they pulled.

• After the starting signal, every charioteer tried to push into the inside lane in order to cover the shortest possible distance. The outcome of the draw for positions was thought to be the product of divine intervention.

• Women were forbidden from competing, but were allowed to breed horses and to take part in chariot races through the participation of their horses and charioteers. Women entered the stadium on penalty of death, but Kallipateira was allowed to go unpunished because she hailed from a family of Olympic champions.

• Cynisca is referred to as an Olympic champion because the victory crowns in equestrian competitions were received by the owner of the winning horses or chariot, not by the charioteer or rider. Thus, we also find in the Olympic victors’ lists from equestrian events the names of such well-known figures as the Athenian tyrant Peisistratus, King Philip II of Macedon and the Roman Emperor Tiberius. AD

49, 207th OLYMPIAD

A Dancing Boxer

Ancient boxing is an event that is barely recognizable today. Melankomas, a handsome athlete with a gentle appearance, has demonstrated that the thrilling but sometimes violent and lethal sport can also be approached peacefully. The new Olympic champion from Caria defeated his opponent and took the olive-wreath crown using a very special technique through which he avoided injury to himself and his opponents – a fact that brings even greater glory to his triumph. The athlete completed all the matches without taking a single punch to his smiling face and without having to hit anyone. Taking advantage of the time limit provided for by the rules, he relied on his extraordinary strength and constant movement – almost as though dancing – to methodically dodge his opponents’ blows, driving them to complete exhaustion and admission of defeat.

• Melankomas died quite young, but in his short life he reputedly never lost a single match. It has been written that he was Emperor Titus’ lover.

• Competitors in boxing directed punches mainly at each other’s faces and upper torsos, until one of them became exhausted or was forced to admit defeat by raising a forefinger.

• The Spartans avoided competing in the boxing event, as they considered the possibility of defeat too disgraceful.

• Boxing competitors initially wrapped their fists with strips of oxhide, then introduced straps that were further reinforced with tough leather and lined with wool. Later, the Romans added metal beads that could make a boxer’s blows fatal.

Based on texts by prof. Panos Valavanis

Illustrations by Anna Tzortzi

“Women were forbidden from competing, but were allowed to breed horses and to take part in chariot races through the participation of their horses and charioteers.”