Few discoveries in Greek archaeology have captured the imagination of scholars and the public alike as much as the mysterious script known as Linear B. Inscribed on clay tablets dating back to around 1400 BC, Linear B represents an early syllabic script with additional ideographic signs, akin to Egyptian hieroglyphs. It marks a pivotal moment in the early development of the Greek language and proved to be a key in understanding the inner workings of Mycenaean civilization, the setting of much of ancient Greek literature and mythology, including the famous Trojan Epic Cycle. Yet for decades, the script remained unreadable—a tantalizing mystery even to the brightest minds.

That all changed in 1952 when Michael Ventris, an English architect with a passion for cryptography, cracked the enigma with the help of Cambridge classicist and former WWII codebreaker John Chadwick. Their decipherment was revolutionary, revealing a long-lost form of Greek that scholars had initially thought unrelated to the Mycenaeans. It also opened a rare window into the day-to-day workings of a Late Bronze Age culture. But was this achievement solely Ventris and Chadwick’s? Or did they receive crucial help from two overlooked scholars on the other side of the Atlantic?

In this article, we trace the discovery and eventual decipherment of Linear B, the brilliant scholars who made it happen, and explore the script’s connection to other undeciphered ancient writing systems like Linear A, Cretan hieroglyphs, and the mysterious (and significantly older) Dispilio Tablet, with its enigmatic Neolithic markings.

© Shutterstock

The Discovery of Linear B

The story of Linear B begins at the dawn of the 20th century, on the island of Crete. In 1900, the pioneering British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, while excavating the Minoan palace of Knossos, unearthed a treasure trove of clay tablets. They bore two distinct scripts: what Evans would name “Linear A” and “Linear B.”

Linear A, the older of the two, dates back to around 1800 BC and remains undeciphered to this day. Linear B, however, was used later, primarily in administrative records by the Mycenaeans, the first advanced Greek civilization that thrived on mainland Greece and Crete during the second half of the second millennium BC.

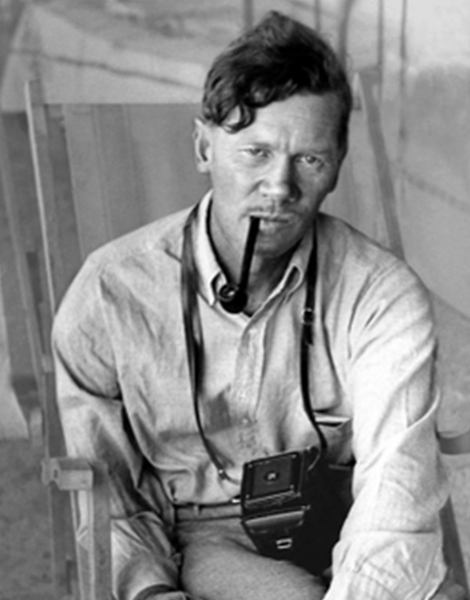

For decades, Linear B was little more than an archaeological curiosity. That is, until 1939, when American archaeologist Carl Blegen of the University of Cincinnati made a critical discovery. While excavating the Palace of Nestor in Pylos, in the southwest Peloponnese, Blegen uncovered over 600 additional tablets inscribed with Linear B. This substantial find provided scholars with a crucial mass of material to work with—without which, deciphering the script would have been like scaling Mount Everest without ropes.

“It was really with Blegen’s finding so many tablets that they were able to decipher the language,” explains Jeff Kramer, an archivist at the University of Cincinnati’s Department of Classics.

The “Mount Everest of Greek Archaeology”

Despite Blegen’s discovery, Linear B remained an unsolvable puzzle. The tablets found at Knossos, Pylos, and other Mycenaean sites (Mycenae, Thebes, and Tiryns) tantalized scholars. The symbols seemed familiar, yet no one could say for certain what language they represented—or whether they represented any language at all. Was it an archaic form of Greek? Or was it something entirely separate? At the time, many believed it was related to Etruscan, an ancient language from central Italy.

Deciphering the 3,500-year-old script was compared to scaling “the Mount Everest of Greek archaeology.”

Throughout the 1940s, Alice Kober, a classics professor at Brooklyn College, made significant strides toward unraveling the mystery. Kober painstakingly cataloged the symbols, identifying patterns and recurring sequences. Working with Emmett Bennett Jr., a scholar and former student of Blegen’s, Kober tracked the frequency of symbols and how they appeared within words. Her observation that certain word endings might reflect grammatical structures (inflection)—similar to conjugations in Greek and other Indo-European languages—was a major breakthrough.

It’s fascinating to note that this progress occurred during a time of global fascination with cryptography, spurred by World War II. Bennett himself worked as a cryptanalyst, deciphering coded Japanese messages for the Allies.

Tragically, Kober died in 1950 at the age of just 43, her work unfinished. As American linguist Adelaide Hahn wrote in her obituary for Kober: “If and when this decipherment is ultimately achieved, surely her careful and faithful spade-work will be found to have played a part therein.”

Ventris’ Breakthrough

The mantle of decoding Linear B then fell to Michael Ventris, a gifted linguist with an obsession for cracking codes. Ventris, who had corresponded with Sir Arthur Evans since his boyhood, built on Kober’s research. He had long been fascinated by Linear B, and following his service as an RAF navigator during World War II, he was ready to fully dedicate himself to the puzzle.

With the assistance of John Chadwick, a former WWII codebreaker who worked at the top-secret Bletchley Park (think Alan Turing, et al.), Ventris made a groundbreaking discovery in 1952: Linear B was, against all initial skepticism, an early form of Greek.

While some Linear B tablets had been discovered on the Greek mainland, Ventris shrewdly noted that certain combinations of symbols appeared only on the tablets from Crete. He hypothesized that these might represent place names on the island—a theory that proved correct. Using the symbols he was able to decipher from this breakthrough, Ventris quickly unlocked much of the text and determined that the language behind Linear B was, in fact, Greek. His discovery was groundbreaking, as it revealed a Greek-speaking Minoan-Mycenaean culture on Crete and pushed back the earliest known use of written Greek by several centuries.

Nevertheless, Ventris’s achievement did not come out of nowhere. “Kober and Bennett built the staircase that Ventris ascended,” notes Kramer. “He didn’t build the risers or the steps, but he did take the final step that Kober may have taken if she had lived.”

Tragically, neither Kober nor Ventris would live to fully enjoy their triumph. Ventris died in a car accident in 1956 at the age of 34, a few weeks before the final publication of “Documents in Mycenaean Greek,” co-authored with Chadwick. Despite some initial resistance from the scholarly community, the decipherment of Linear B revolutionized the study of Mycenaean Greece, unlocking a lost world and forever altering our understanding of this Bronze Age civilization.

The Tablets Speak: What Linear B Revealed

When Ventris and Chadwick cracked Linear B, the texts they uncovered were not epic poems or grand mythological tales, but more mundane administrative records. In all, the writing system consists of eighty-seven syllabic signs, i.e., symbols that represent sounds, and over a hundred ideographic signs, representing objects, units of measurement, or commodities.

According to Thomas Palaima, professor emeritus at the University of Texas at Austin, the tablets mostly record the management of resources like grain, livestock, and labor. “They don’t write histories or poetry. They don’t send letters,” he explains. “These are records that keep track of who’s doing what, where, and how they’re doing it.”

But what might seem like dry bureaucratic details to us today was actually a treasure trove of information for archaeologists—offering rare insights into the economic structure of Mycenaean society and even their religious practices.

“We see a lot of feasting texts for gods and lots of names for chariots, armor and animals. How many sheep. Who owns the flocks. What shepherds are on duty. And how many are available for the next feast,” adds Palaima.

The Undeciphered Sibling

While Linear B was deciphered, its older sibling, Linear A, remains an enduring mystery. Used by the Minoans between 1800 and 1450 BC, Linear A shares symbols with Linear B, but the language it represents has yet to be identified. The relatively short and repetitive nature of most surviving inscriptions has stymied scholars’ efforts to decipher it. Linear A bears some resemblance to the enigmatic Phaistos Disk, discovered in 1908, which remains one of the greatest puzzles of ancient Crete.

Similarly, Cretan hieroglyphs, used slightly earlier than Linear A, remain undeciphered. Many of their symbols bear a resemblance to Egyptian hieroglyphs, adding another layer of intrigue.

An Even Older Puzzle

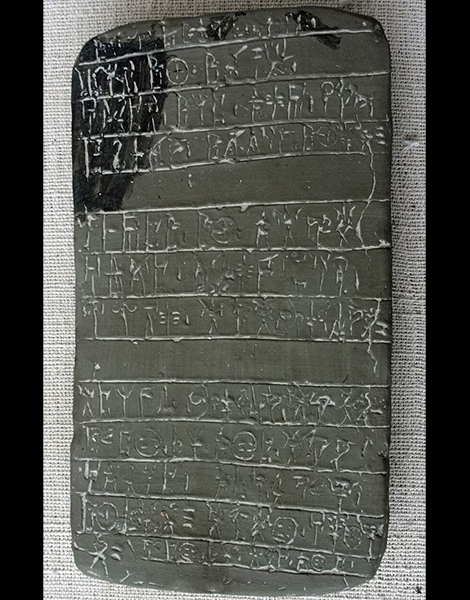

Beyond Linear A and B, Greece holds yet another mystery—the Dispilio Tablet. Discovered in 1993 at a Neolithic lakeshore settlement near Kastoria in Western Macedonia, this wooden tablet, carbon-dated to around 5260 BC, bears incised markings that could represent one of the earliest known writing systems from anywhere in the world. Indeed, if these marks are a form of writing, the Dispilio Tablet would predate both Linear A and B by thousands of years.

Scholars remain divided on whether the marks are an early form of writing or merely decorative. But much like Linear A, the scarcity of material leaves the question tantalizingly open.

The wooden tablet is currently undergoing conservation before scholars attempt to decipher its mysterious markings.

The Lasting Legacy of Linear B

The decipherment of Linear B was more than just an archaeological achievement—it was a testament to collaboration and perseverance. Ventris, Chadwick, Kober, and Bennett, working across disciplines on either side of the Atlantic, succeeded in cracking a code that had been silent for over 3,000 years.

Linear B continues to inspire scholars today. New discoveries and advances in technology may one day unravel the secrets of Linear A, and the Dispilio Tablet remains a compelling puzzle for future generations. But for now, the decipherment of Linear B stands as a shining example of human ingenuity and our enduring quest to understand the distant past.