Neoclassical Architecture: From Greece to the World

Discover how ancient Greek architecture inspired...

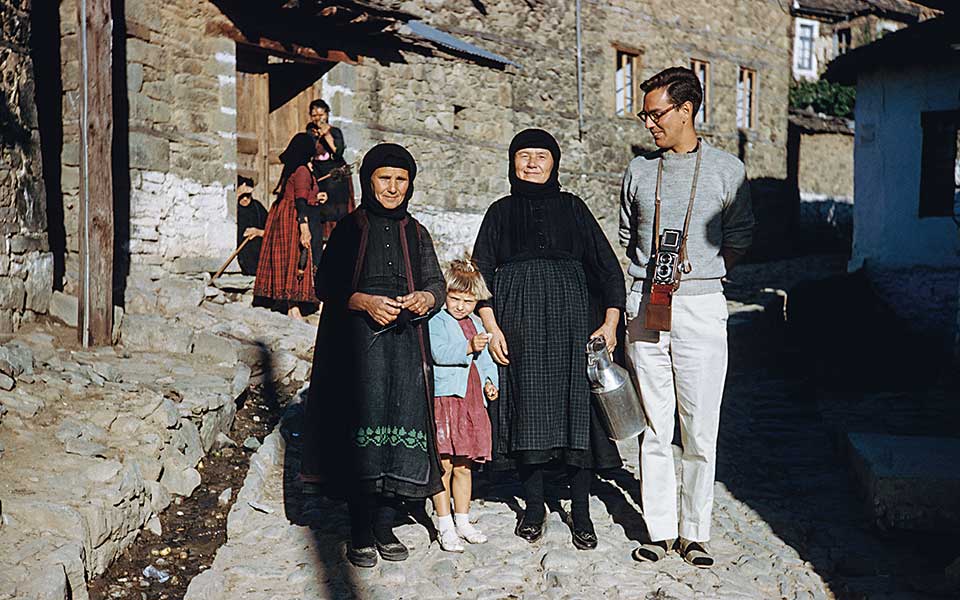

Photographer Robert McCabe strikes a pose with local residents in the village of Metsovo, 1961, long before it became a tourist destination.

© Charles McCabe

Throughout the centuries, migration, commerce and war brought Greeks to foreign lands, where they sometimes found themselves in need of shelter, assistance or protection. The phrase “They ate bread and salt,” meaning that a group sat together at a table and shared food, was used to express a strong bond of friendship. Only “bread-stompers,” or ingrates, would trample on such bonds: that pejorative term was used to describe those who, after having been given welcome and food, which is to say “hospitality,” turned against the family that had offered them.

In Menander, we find the exhortation “Give welcome to strangers, for at some point you yourself will be a stranger.” Gregory the Theologian (329-390 C.E.), Archbishop of Constantinople, urged people to “welcome strangers, lest you become a stranger to God.” The friendly relations that ancient hospitality created were, in fact, so strong that they were passed on to descendants as a valuable legacy; they functioned reciprocally as well, no matter how much time had passed.

A characteristic example from the Iliad is that of the Achaean Diomedes and the Trojan ally Glaukos, who, as they are fighting one another, learn that their ancestors were bound by the ties of hospitality. They stop fighting and exchange their armor, in order to seal their own inherited friendship.

In ancient times, hospitality was seen as a hallmark of civilization. In the Odyssey, when Odysseus washes up on the shore of the Phaeacians, he wonders aloud whether the inhabitants of the land are civilized people who know the rules of hospitality, or wild men who don’t know how to welcome or honor guests.

Lambrini Plati, Ano Peristeri, 1961.

© Robert A. McCabe

The first mate of the caique “Eleftheria,” in the Sporades, 1963.

© Robert A. McCabe

The ritual of hospitality seems to obey a relatively simple principle: the stranger is an unknown, and has to be treated with circumspection. He is the other, he’s different, he may be dangerous, an enemy, someone fleeing persecution or the law. On the other hand, he may just be a simple visitor or traveler.

The ritual of hospitality will ease the stranger’s transition from the strange (mysterious and perhaps even taboo) to the familiar (as, for instance, in Odysseus’ meeting with Nausicaa on the island of the Phaeacians). The path from stranger to friend involves a series of intermediary steps that may be seen as a test or a trial that runs from initial recognition and transformation to a determination of what the stranger really is: a visitor, a friend, an enemy or a potential member of the family or of the community.

In the traditional societies of the ancient Greek world, social groups existed on a small scale: a nomadic group of herdsmen, a shepherds’ encampment, a village. In such small communities, the person obliged to host the stranger was the one who was best able to observe the conventions of welcome: this was usually either the most well-to-do person or the community leader (or mukhtar, during Ottoman times).

In other words, hospitality took place either in the context of the family or of the community. In many mountain villages of Central and Northern Greece, in order for those passing through – including itinerant craftspeople such as tailors, builders and others – to be ensured hospitality and spared the harsh weather conditions, there was a special structure, the amiliko, or community guesthouse (from the Turkish amil, the “monk’s cell”), which usually belonged to the church or to the community. This is where those passing through would stay, and the villagers took turns providing their visitors with food.

Yannis Dikaiolakis on the waterfront on Mykonos, 1957.

© Robert A. McCabe

Young waiter on Alonissos, 1963.

© Robert A. McCabe

In the past, the possibility of the appearance of strangers was always anticipated. Every household set aside homemade wine or spirits to offer to visitors. There were always almonds, walnuts, spoon sweets or Turkish delight in the pantry. The woman of the house had small glasses and utensils for the express purpose of serving these treats.

The stranger would be seated at the head of the table, the place of honor, and offered the first plate with the best portion. The man of the house would cross himself, saying “Welcome.” During the meal, he would encourage the stranger not to be shy, to eat as if they were in their own home. And when the stranger left, they would never be empty-handed, but always carrying gifts of food and wine for the road. What’s more, the host would often show them the way, accompanying them for a portion of the onward journey.

Schoolchildren on Patmos taking part in celebrations marking Greek Independence Day.

© Robert A. McCabe

Maria Ioakim, Mykonos, 1957.

© Robert A. McCabe

In almost all of the Greek world, there was the custom of making an extra loaf when baking bread. Frequent references can be found to “Christ’s portion,” which is to say the Stranger’s portion, since any stranger could be Christ himself. Even for a family’s everyday meal, the woman of the house always made an extra portion, which was for the stranger. This portion was real, not imaginary; there was always a bit extra, more than necessary.

This practice of household economy is still expressed in local idiomatic sayings: “Cook for many, but set the table for few” (Cyprus and throughout Greece) or “Six people in the household, plus a stranger, makes ten” (Kefalonia). A stranger could come by at any moment and need the community’s aid: “The blind man needs guiding, and the stranger a place to stay…”

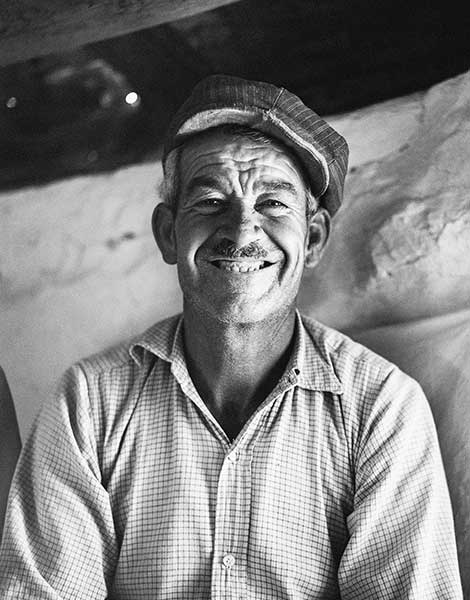

Portrait of a miller in his windmill on Ios, 1963.

© Robert A. McCabe

Unknown woman in the Cyclades.

© Robert A. McCabe

In the absence of a visitor, this extra food did not go to waste; the next day, it was shared with the poor. Local communities knew who was in need, and they made sure to send those people leftovers without insulting them. This custom, which never really disappeared from rural communities, became visible again during the recent economic crisis. Not everyone in need ended up at the soup kitchens organized by the church, the local community, or citizens’ groups. In the villages in particular, but in many city neighborhoods as well, food was left at a specific place with the understanding that whoever was in need should take it, without feeling embarrassed about having to do so.

Relationships created by hospitality are not wholly altruistic; they contain an element of “exchange.” Whoever assumes the role of host enjoys the honor that comes from being in a position to offer hospitality. To spread this honor, it was once customary in a number of regions for strangers to be hosted by different families in turn, one day in one house in the village, the next day in another. If the stranger was staying in the community guesthouse, villagers would take turns sending food over for him.

When someone stayed for a length of time, he had an obligation to develop relations with everyone in the community and to respect their way of life; otherwise, they would think he was being disdainful. Even today, while strangers or visitors are usually associated with some “favored interlocutor” who welcomes them, they still have to keep in mind their duty to speak with everyone in the community that has welcomed them and to pay everyone the proper attention.

Of course, there is always the understanding that this is all temporary, reflected in a saying that isn’t exclusively Greek: “After three days, both fish and visitors start to smell.”

Travelling to Mykonos in deck class seating on the “Despina.” The ship, originally built for the US Navy, found its way to Greece after WWII.

© Robert A. McCabe

Dancing at Aghios Panteleimon Monastery in Mykonos at a baptism on the saint’s feast day in 1955. The woman dancing is Argyro Kypraiou.

© Robert A. McCabe

The photographer Robert McCabe captured the kindness, hospitality and zest for life that’s always been so characteristic of Greece.

Αmong those who witnessed Greece’s transition and transformation from a poor, agrarian country into one of the world’s most popular tourist destinations is the American photographer Robert McCabe, who first visited this country 65 years ago. Over the ensuing years, he’s had the privilege of experiencing the spontaneous, selfless philoxenia of the local inhabitants of the islands and the mainland. Those residents once lived lives of tremendous deprivation, but the way in which they welcomed and took care of foreigners was extremely generous, both in intangible and material terms, and that type of welcome has not disappeared.

On his first trip to Greece, Robert accompanied his brother Charles, who had been encouraged by his good friend Petros Nomikos from Santorini to visit the country. According to the photographer, the hospitality shown towards a foreigner was something remarkable. Greeks behaved towards the visitor as though this person were an honored member of their own family.

“In my eyes, in a sense they carried on the tradition of Homer, back when people believed that someone arriving from a foreign place might just be a god in disguise. The most striking example was the time when I went to the island of Ios with a friend, our family doctor, in fact. The mayor of the island gave up his own bed for my friend and he himself slept on the floor, as though it were the most natural thing in the world. By today’s standards, something like that would be considered insane.”

Yet another such moment occurred in Santorini, in 1963. “I visited the island with the doctor I’ve already mentioned [and others],” McCabe recalls. “For the whole time we were there, we ate, day and night, at the only taverna on the island, at Louca’s in Fira. The owner was a cheerful but poor man. After every meal, we’d go up to him to pay the bill for our party, which had a total of five people in it. But he’d always reply, ‘Tomorrow.’ On the last day, when I went to settle the final bill, he refused to take any money, uttering one of the few words he knew in any foreign language: ‘Souvenir.’ He wanted us to remember him after leaving the island. And the truth is that I still do remember him, even today.”

Even today, something remains of that selflessness. Many of the people who live in the Greek provinces still possess philotimo (a sense of duty and honor), when it comes to the generosity they show their guests. Other things have changed, however; what saddens Robert McCabe most is that some of the most beautiful areas in the country have been spoiled through unbridled and haphazard development. In many cases, what has been lost, along with the pure and genuine hospitality of the locals, has been the older generations’ wise understanding of how to coexist in harmony with nature.

Discover how ancient Greek architecture inspired...

In Syntagma Square, marble, flame, and...

A major restoration project is bringing...

The Kerameikos archaeological site provides a...