What’s Really Happening in Messinia?

The Olympic elite, Hollywood’s finest, the...

Pelops, racing away from Oenomaus, with Hippodamia; from an Attic red-figure neck amphora, 410 BC. (National Archaeological Museum, Arezzo, Italy)

© VisualHellas.gr

The importance and depth of meaning that athletics and athletic competition held for Greeks in the ancient world is difficult to overestimate. The idea of physical or athletic prowess went right to the heart of what constituted an upstanding, admirable, well-educated, disciplined and capable individual. An already age-old familiarity with athletics and systematic physical training can be traced back to Homer’s Iliad (ca. 8th-7th c. BC), the story of the Trojan War, which along with its sequel, The Odyssey, and Hesiod’s roughly contemporary poems, mark the oldest known written works in western literature. The hero Achilles, who was encouraged by his father Peleus “always to be bravest and excel over others” (Iliad, 11.780), represented the archetypal youth, ideal warrior and human incarnation of divine perfection. Athletic training, in part as preparation for military service, formed a key part of his education, along with music and song. To compete and to win are essential, timeless elements of being Greek.

From at least the Late Bronze Age, the heroic era referred to by Homer, demonstrations of athletic ability were common features in the life of royals and other political or social elites. Minoan and Mycenaean wall paintings, painted pottery and other art depict bull leaping, boxing, wrestling, running and chariot racing. According to Homer’s description, which also reflects the culture of his own time, athletic contests were organized as funeral games or special presentations in honor of a guest. Yet the threads of athleticism, competition, mythology and religion, as we begin to discern from characters such as Achilles, were also intertwined from earliest times.

Athletic competitions eventually became a formalized, panhellenic institution at Olympia, controlled mostly by the nearby city of Elis, with the first Games traditionally dated to 776 BC. Long before that momentous date, however, ritual sporting events were already being conducted there during the local worship of Zeus. Nevertheless, athletics were of secondary importance. Archaeologist Catherine Morgan has argued that the many bronze figurines and tripods unearthed at Olympia were votive offerings dedicated to Zeus, not prizes awarded in athletic games. Initially, the sanctuary at Olympia was foremost a center of religion, not athletics, and it was home to a range of deities and heroes including not only Zeus and Hera, but also Pelops – after whom the Peloponnese was named – his bride Hippodamia and Demeter Chamyne, whose altar stood in the stadium and whose priestess was the only married woman granted access to the arena. Herakles, too, in various forms, was closely associated with Olympia.

“From at least the Late Bronze Age, the heroic era referred to by Homer, demonstrations of athletic ability were common features in the life of royals and other political or social elites.”

Olympia’s stadium, view to the southeast. Visible are the altar of Demeter Chamyne, the reserved area for judges and the starting line.

© Vangelis Zavos, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund

View through the entrance tunnel from inside Olympia’s stadium, toward the Altis, the sanctuary’s sacred central grove.

© Vangelis Zavos, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund

Herakles’ fifth labor: cleaning out the stables of King Augeas. A metope panel from the Temple of Zeus, ca. 470 BC - ca. 457 BC. (Olympia Archaeological Museum)

© Vangelis Zavos, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund

The local hero Pelops, who had to compete in a chariot race to win the lovely Hippodamia’s hand from her father King Oenomaus of Pisa, was credited by some as the legendary founder of the Olympic Games. Alternative founding figures included Neleus and Pelius, two sons of Poseidon, as well as the kings of Elis, or even Pisos, the eponymous hero of the Eleans’ longstanding rival Pisa. Another tradition named Hippodamia as the founder of the Heraia, the women’s running competition.

The Classical poet Pindar (ca. 522 – ca. 443 BC) wrote that the mighty hero Herakles had established the Olympian sanctuary, defining the boundaries of the sacred grove (Altis) and dedicating the first Olympic Games to Zeus. Herakles undertook these actions in celebration of his having completed one of his 12 labors in the vicinity of Olympia: the purifying of Elean King Augeas’ stables through a diversion of the Alpheios River. Herakles was also said to have laid out the first stadium at Olympia and to have introduced the wild olive to the area, from which the victory wreaths were prepared for the crowning of triumphant athletes.

By the 5th century BC, the concepts of agon (struggle, contest, competition) and nike (victory) were such essential components of Greek life that they came to be considered divine figures, with sculpted and other tangible, artistic depictions of them being erected as offerings in the Olympian sanctuary. One of the great showcases of Competition and Victory could be found on the Acropolis in Athens, where the Parthenon’s sculpted metopes displayed legendary or mythological contests with various levels of meaning for ancient Greeks, including the Trojan War (Greeks vs foreign foes), the Centauromachy (struggle of law/order vs chaos), the Gigantomachy (struggle of civilized people vs mythical monsters) and the Amazonomachy (again a reminder of Greek/Athenian supremacy).

Competition was seen as well on the Parthenon’s western pediment, where Athena and Poseidon vied for the position of divine patron of Athens. At Olympia itself, the Centauromachy again appeared in a prominent position in the Zeus temple’s western pediment, while the eastern pediment held a magnificent late Archaic-early Classical scene of Pelops preparing for his chariot race against Oenomaus (now in the Olympia Archaeological Museum). The labors of Herakles were displayed on the temple’s metopes. Virtually everywhere visitors to Olympia looked, they were faced with gods, heroes, victorious athletes and other reminders of agon, nike and the exalted role of competitive sport. Pindar suggested in his victory odes that athletic triumph represented the greatest height to which mortals could aspire.

“Pindar wrote that the mighty hero Herakles had established the Olympian sanctuary, defining the boundaries of the sacred grove and dedicating the first Olympic Games to Zeus.”

Bronze 6th century BC figurine of an old man with a staff, possibly Nestor, from the rim of a votive vessel. (Olympia Archaeological Museum)

© Vangelis Zavos, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund

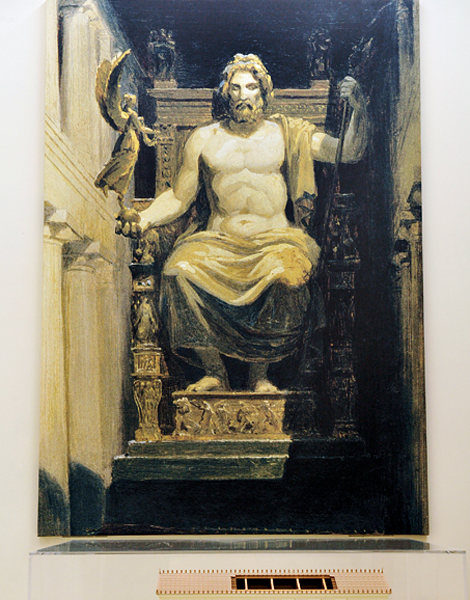

Reconstruction of Pheidias’ seated, gold and ivory cult statue of Olympian Zeus (ca. 430 BC), one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

© Vangelis Zavos, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund

With the ascendancy of athletics’ popularity, and ever-growing numbers of visitors flocking to Olympia, the Games became less about religious worship and more a form of entertainment, assertion of ethnic identity, or instrument of diplomatic and political expediency for a wide spectrum of athletes and spectators from all walks of life. This disentanglement is witnessed in the gradual relocation of the stadium out of the sacred Altis to its present eastern location outside the sanctuary, where boisterous crowds were also more easily managed and accommodated. Although Zeus and the other divinities continued to be respected in name, it was athletes who increasingly became the people’s much-admired gods. Philosophers and other intellectuals, much like today, came to resent the great esteem and privilege offered to athletes, suggesting that true perfection came only with a balance of mind and body, but enthusiasm for sport and athletic glory continued to rise.

Through the Roman period, the athletic games at Olympia and elsewhere, and all that they entailed, became more and more like sporting events we might recognize today. Athletics remained a channel for great aspirations and idealistic personal or societal/political aims, but the lifeblood of the ancient Olympic Games was always fierce competition and victory, often at any cost. Like today, officials and judges (Hellanodikai) had to be vigilant about corruption. The line of “Zanes,” Zeus statues on bases bearing moralistic inscriptions, which were erected outside the stadium by athletes caught cheating, were a constant reminder that rule-breaking continued to be a problem.

Olympia’s universal fame also came from one of its greatest attractions: an enormous seated cult statue of Zeus, more than 13m high, constructed from gold and ivory by the renowned sculptor Pheidias (ca. 430 BC), which ranked as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. In the end, however, Olympia was severely sacked by the Roman general Sulla in 80 BC, invaded by the marauding Heruli tribe in AD 267 and finally succumbed to restrictions and closures imposed on pagan sanctuaries by the edicts of the emperors Theodosius I and II in the late 4th and early 5th centuries AD.

“Virtually everywhere visitors looked, they were faced with gods, heroes, victorious athletes and other reminders of agon, nike and the exalted role of competitive sport.”