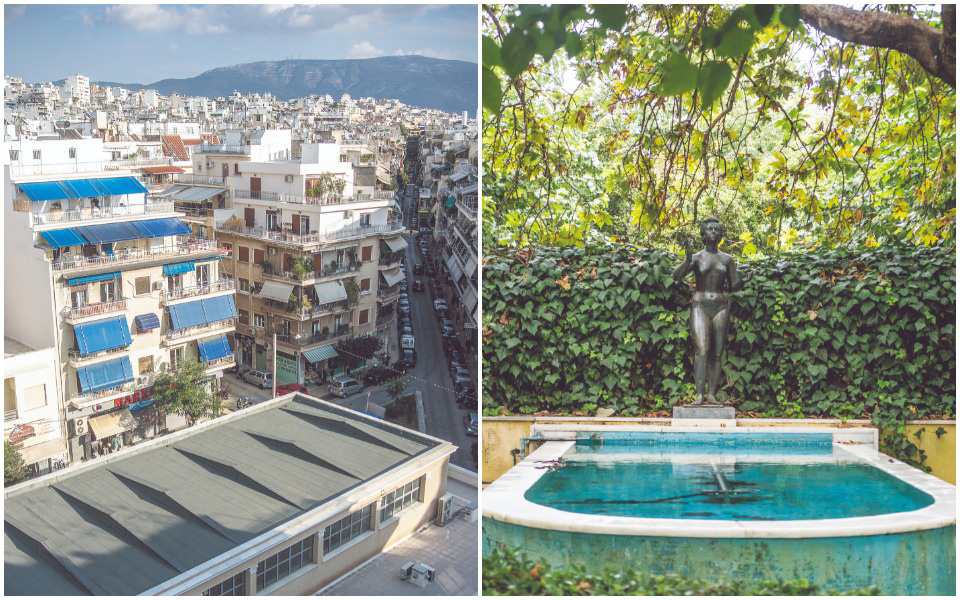

Pedion tou Areos park to the south, the Tourkovounia hills to the east, Galatsi and Alepotrypa Hill to the north and Patission Street to the west: These form the boundaries of Kypseli, a neighborhood that was part of the countryside until Athens became the capital of Greece in 1834. A century later it had acquired a number of exceptional neoclassical and eclectic buildings, but it was not until one of its streams, the Levidi, was rechanneled underground and covered with a street called Fokionos Negri, that the area started becoming properly urban. Well-off families began buying or renting apartments in modern buildings that promised a glamorous city life, but construction exploded after World War II when Kypseli was also washed by the flood of immigration comprising rural Greeks dreaming of a better life in the capital. After that, Kypseli just kept swelling.

Those of us who grew up there in the 1970s and 80s saw the evidence of this process in its streets, where we’d often hear the cliche: “Kypseli is the most densely populated part of the world after Hong Kong.” It is true that there was something dystopian about our claustrophobic neighborhood, but the same could be said for many other parts of this hastily and haphazardly built city.

© Nikos Kokkalias

There were, however, small windows of fresh air. Fokionos Negri, for example, bubbled constantly with laughter, games, flirtations and discussions. Those 750 meters or so from Kypseli’s main square to Patission Street were something like a human amusement park, pulsating with color and artistic energy. Cinemas, theaters and cultural spaces were everywhere – not to mention some of Athens’ most legendary restaurants and bars.

The other big window was Pedion tou Areos. Our school, Athens’ 60th High and Middle School, was one of the neighborhood’s most powerful architectural symbols and stood halfway down Kypselis Street as it sloped toward the park. This gave the school a view of greenery and the spot where the sun used to set, bathing the narrow streets in an orange light for a few fleeting minutes. Here on Kypseli’s western border, the Panellinios sports club was the only place in the city center where you could take tennis lessons apart from the more insular Athens Tennis Club, or do other, more “working-class” sports, like boxing, wrestling or basketball, which became very popular, very quickly in the 80s. Panellinios was the kind of place where tennis players and boxers would hang out together, a coexistence that defined the human element in the neighborhood. Kypseli’s insufferable concrete and narrow streets have always represented a colorful celebration of multifaceted urban life.

Flight of the old-timers

Promises of a life of clover sent Kypseli’s older residents running to the northern suburbs en masse in the early 1980s. This was followed in the 90s by an influx of immigrants from the Eastern bloc and then in the 2000s from Africa. Kypseli was written off by many of its remaining old-timers, but all these new people coming from different lands somehow managed to stick together.

Kypseli is back on its way up nowadays. We could say that it’s experiencing its third youth after that of the 1930s and 60s. What explains the phenomenon and where is it going? Being among those who grew up there but left years ago, this writer is in no position to answer those questions. But four die-hard “Kypselites” we spoke to are.

Kypseli-born and bred author Christos Chomenidis recently published a book titled “Tzimis in Kypseli,” whose protagonist is an impresario in present-day Fokionos Negri. I ask whether this reflects the area’s recent popularity. “The story could have been set in other Athenian neighborhoods, but it takes place in Kypseli because I happen to know it better – I’ve lived here all my life. But, you know, Tzimis runs a theater that stages low comedy, when real Kypseli had very good theater,” he says.

© Perikles Merakos

Filmmaker Lefteris Charitos also reminisces on those theaters. “Kypseli was always an artistic neighborhood because it had theaters and movie theaters, and I don’t just mean art-house cinemas like Studio. I mean countless commercial movie theaters, both indoors and out,” he comments.

“Places like the Select pastry shop were also cultural venues, though. I used to go there on Sundays, in the late 1970s, with my dad and I remember feeling like I was doing something terribly important just by being there,” he adds.

Select also features strongly in Chomenidis’ childhood memories. “I remember various aunts sitting there, eating chocolate cake,” he says.

“The neighborhood at the time was upper middle class, but this started changing in the early 1980s. I remember waiting for the Athens College school bus and the crowd getting thinner all the time as families gradually moved to the northern suburbs,” adds Chomenidis, referring to a well-known private school. “Kypseli declined, something that inevitably meant it would start climbing up again.”

Now that this is the case, what will happen?

“It has structural problems that do not allow it to climb too far up,” says the award-winning writer. “It has narrow streets and sidewalks that often make walking frightening. And because most of the apartment buildings are old, they don’t have independent heating or parking, which is in short supply more generally. So, unless it’s torn down and rebuilt, what I think it may turn into is a young and arty neighborhood.”

Young people were also attracted to Kypseli back in the 1980s thanks to the neighborhood’s reputation for tolerance of alternative subcultures, similar to Exarchia.

Giorgos Fertakis used to own Sonic Boom Records, a music store that was around from 1995 to 2013, first on Kypselis Street and then on Syrou. On a blog he wrote until recently, he recounted being alerted by a friend to the presence of legendary punk-rock band The Ramones eating souvlaki at a local taverna after a gig in Athens in May 1989. “There they were, in Thraka, over a huge number of dishes and beers,” he said.

© Shutterstock

His portrait of Kypseli is painted through the prism of its relationship with music. “I have been inside countless local houses as a result of my work, buying old records from private and family collections. I almost always came across very decent or even impressive collections. And this, I believe, is a sign of the area’s people and their cultivation. Kypseli’s relationship with music is also evidenced by the sheer number of record stores it used to have – I put them at at least 30,” Fertakis tells Kathimerini.

So, was it this presence of art and culture that made Kypseli such a melting pot, so tolerant of diversity?

“There’s always been a sense of freedom in Kypseli. You could go out wearing your pants back-to-front and not hear a peep,” says Charitos. “It’s never been associated with tittle-tattle, even though there was much to gossip about.”

Chomenidis agrees. “I used to go out in my pajamas to get cigarettes from the corner store and no one would bat an eye,” he says.

Why? “Probably because the area’s residents were bourgeois enough not to be prejudiced,” he answers. I can’t help asking why he believes this would not also be the case in Kolonaki, another of Athens’ pre-eminent bourgeois neighborhoods. “The difference between Kypseli and Kolonaki is that residents in the former couldn’t care less, while in the latter they’d think you were trying to make a point,” is his delightful response.

Seeking a new identity

Michalis Papadakis also stuck with the neighborhood through the bad times and, being in real estate, is as knowledgeable about Kypseli as he is fond of it. “Kypseli is always alive, never stagnant. And, as a resident, if you want to stay active, you need to keep up with these changes and transitions. Now it’s applied for a new identity, but I don’t know if the papers have gone through,” he quips.

“What I do know is that it’s changing. New pieces are being added to the puzzle. I saw this a couple of years ago when the first ‘displaced’ people appeared, internal city migrants, young people who lived in other neighborhoods (Koukaki, Ilissia, Neapoli and Exarchia), where their landlords decided to turn their properties into hotels. Most had spent a few years abroad and were comfortable with cultural diversity and willing to experience something new. The first few chapters have already been written. Now we’re waiting for the next ones with anticipation,” he adds.

This article was previously published at ekathimerini.com.