A Summer Visit to the Acropolis: What Tourists...

Tourists share the highs and lows...

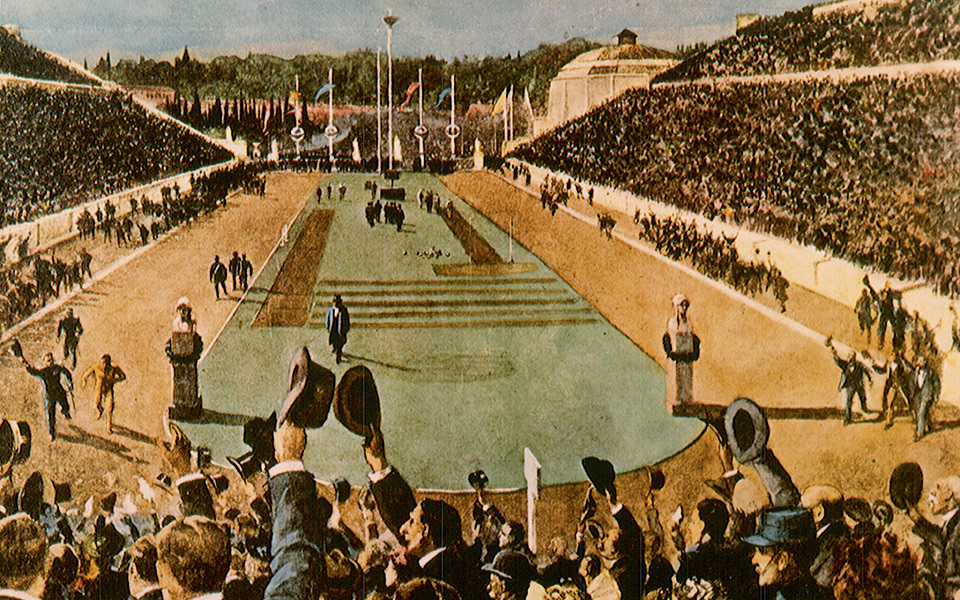

A painting of the crowd cheering for Spyros Louis, winner of the first Olympic Marathon in 1896. The Greek runner’s victory came as a crowning achievement for the host country.

© IOC Olympic Museum/Getty Images/Ideal Image

When it was announced in 1894 that the first modern Olympics would take place in Athens in less than two years, the news did not spread like wildfire, or prompt the kind of widespread enthusiasm among the people and politicians that we see on television today when a country is bestowed the honor of organizing the next Olympics. After all, the world was not interconnected in the way it is today. The telephone, which would eventually replace the telegraph, had only just arrived, and television broadcasts would not take place for another 35 years. Newspapers, however, did exist, and local papers described the euphoria the news generated among Athenians. They also noted that, as far as the Greek government was concerned, the news was received with less enthusiasm.

For those Europeans with a classical education, it was self-evident that Athens was entitled to this honor; the city was a benchmark of Western civilization. It was where democracy and the principles of philosophy and science had been born, as well as the place where great masterpieces of art had been created. Therefore, the International Athletic Congress in Paris (16-24 June, 1894) gladly accepted the proposal from the newly-created International Olympic Committee (IOC) that Athens host the Games, and the announcement was sent by telegraph to Greece.

For many, it was welcome news indeed. Athens was developing rapidly in 1894, both as a city and as an important spiritual, cultural and economic center for the nation. For the government, however, there was genuine reason for pessimism. The task of getting the city ready for the Games was immense, not only because of the time constraints – the scale of construction that needed to be completed in less than two years was staggering – but also because of the cost involved. Just a year earlier, in 1893, the prime minister had informed Parliament that the country was bankrupt and that Athens lacked the necessary sports facilities for the Games. But – as Greek public opinion deemed that the revival of Olympic ideals was a point of national pride, a bet that had to be won in order to prove that modern Greeks were worthy successors to their ancient ancestors – the government had no choice.

“The task of getting the city ready for the Games was immense, not only because of the time constraints – the scale of construction that needed to be completed in less than two years was staggering – but also because of the cost involved. ”

The enthusiasm of the Athenian people exceeded all expectations, and the mobilization of workers took place on an unprecedented scale. At the same time, the efforts of the Greek Olympic Committee were supported by Greeks everywhere, including wealthy expatriates who assisted with the project and its finances. The marble Panathenaic Stadium, where most of the events would take place, rebuilt on the foundations of the original ancient structure (4th century BC), became a gleaming venue capable of holding more than 50,000 spectators. The city also built a brand-new firing range for shooting events and, despite initial disagreements (Baron de Coubertin, president of the International Olympic Committee, favored one design, the crown prince of Greece another) constructed a velodrome; since the bicycle was now extremely popular in Europe, particularly in France, the new velodrome was designed with a capacity for 7,000 spectators. In Pireaus, special facilities were constructed for swimming events, while in Faliro on the western Attic coast, work was done on the area assigned to rowing and sailing events.

The 1896 Olympics were, without a doubt, a truly prestigious sporting event, with an estimated 285 athletes (all male) from 14 countries competing in 43 different events. Hosting the event, moreover, was a glorious celebration for Athenians, who welcomed a large number of visitors and took pride in showing them imposing public edifices and the mansions of wealthy citizens, which rendered the city beautiful with their splendid, neoclassical architecture, as well as the other more humble homes and buildings that also made up the burgeoning city.

By this time, archaeological excavations and restorations highlighting the glorious monuments of the Acropolis and the temple of Hephaestus in Thiseio had already begun, while the Acropolis Museum and the National Archaeological Museum were in operation, too. Foreign visitors were thus able to enjoy the antiquities of the Greek capital, often on organized tours created expressly for the period of the Games.

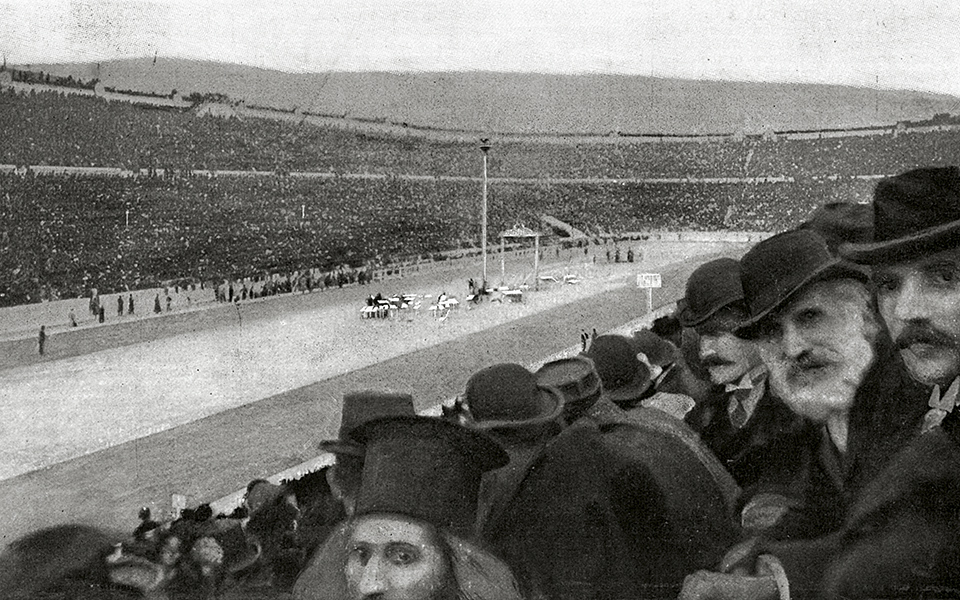

Looking down the stadium for the finish of a race.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

The plans laid for welcoming and accommodating visitors from abroad worked perfectly. The Olympic Committee’s team responsible for receiving foreign visitors organized all their accommodations, irrespective of whether they were staying at luxury hotels or in private houses offering more affordable lodgings.

Among the visitors were royalty, heads of state, diplomats, politicians and others who, altogether, added a special glamour to the event. There were also a number of correspondents sent from the major newspapers in Europe and America, including The Times of London and The Boston Tribune.

Classical scholars turned out in large numbers, as well as other philhellenes, all of whom traveled by ship, because Greece was not yet connected to the rest of Europe by rail. Most tourists from France came in on the steamer Senegal, while other Europeans chose the route through Venice. Greek railway companies offered special rates and put on additional trains for transfers between Athens and the ports of Patra and Corfu. There were also special agreements made with coachmen to help handle the demand for transportation. Of course, not all visitors were foreign. Many Greeks from rural parts arrived in the capital, piquing the Athenians’ interest and curiosity with their traditional outfits, including the fustanella, a pleated skirt worn by men.

Athens was more than ready for the big celebration, courtesy of a municipal administration that had succeeded in repairing roads, planting trees, improving street lighting and making sure that city squares had been scrubbed clean. The central parts of the city were decorated, main streets and squares were illuminated by arched, gas-lighted tubes, and laurel wreaths and flags of the participating countries adorned the facades of public buildings. The celebratory atmosphere was further enhanced by owners of shops and houses who decorated their properties on their own initiative.

The Greek government’s desire that the Games be a success, and the need to avoid security issues in order to achieve this success, led to the creation of a peculiar “Olympic truce.” This was engineered by the chief constable of Athens who, in a secret meeting with all those local thieves known to the police, appealed to their national pride and persuaded them to refrain from any criminal activity or wrongdoing that could cause embarrassment to the country. He even appointed some of them as guards and assigned them to keep an eye on their foreign “colleagues” who had traveled to Athens in the hope of easy pickings. The truce worked; there was, it seems, not a single theft throughout the Olympics.

“Athens was more than ready for the big celebration, courtesy of a municipal administration that had succeeded in repairing roads, planting trees, improving street lighting and making sure that city squares had been scrubbed clean. ”

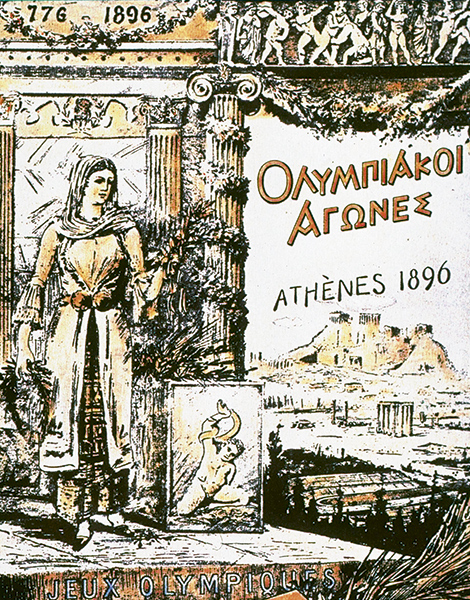

An official poster from the event, on display at the IOC Olympic Museum in Lausanne, Switzerland.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

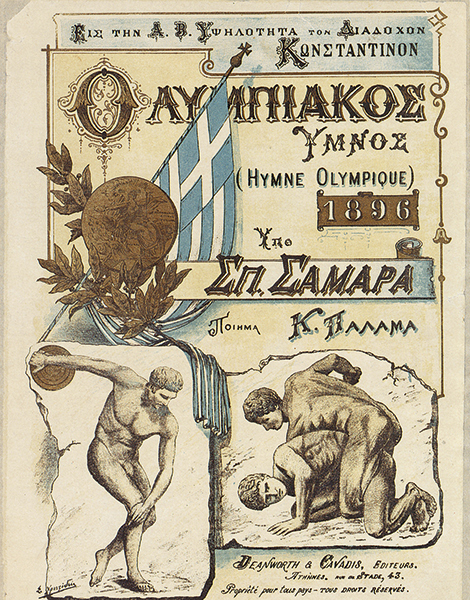

A colored edition, by Deanworth & Gavadis, of the sheet music for the Olympic Hymn, composed by Spyros Samaras, with lyrics from Kostis Palamas.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

The much-awaited moment finally arrived on 25 March, according to the Julian calendar in use in Greece at the time (or on 6 April, according to today’s Gregorian calendar), with the declaration of the start of the first Olympic Games by King George I. The Panathenaic Stadium, packed with spectators, was rocked by a deafening ovation and, immediately afterwards, the Olympic Hymn – with music composed by Spyridon Samaras and lyrics inspired by the poetry of Kostis Palamas – was heard for the first time.

Throughout the Olympic Games of 1896, sports venues were crammed with people cheering for the athletes. During breaks in the competitions, some of Greece’s best philharmonic orchestras played to keep the crowds entertained, while in the evenings, the city’s illuminated squares also hosted musical shows. Other events of light entertainment were taking place around the city as well, all for the amusement of Athenians and sundry visitors alike.

The first night of the Games featured a grand parade that involved all the city’s guilds and associations, while on the evening of the second day, an illuminated Acropolis stole the show. Everyone watched spellbound as the “Sacred Rock” seemed to be set ablaze by the colorful fireworks exploding above it.

Over in Piraeus, an impressive setting was created for the “Venetian feast” – an unbroken chain of lights and colorful candles encircled the entire coastline and made the sea sparkle, reflecting off the boats and military warships in the harbor. The festive atmosphere was complete with a parade of sailors holding torches while orchestras belted out melodies against a backdrop of yet more colorful fireworks.

“The Panathenaic Stadium, packed with spectators, was rocked by a deafening ovation and, immediately afterwards, the Olympic Hymn”

The National Theater and other professional troupes also provided entertainment for the city’s visitors by staging classic works, including plays from the European repertoire, modern Greek dramas and ancient Greek tragedies. Sophocles’ Antigone, staged by an organization using the original text, called The Company in Favor of the Teaching of Ancient Dramas, raised a storm of debate and helped spur on the revival of the ancient dramatists.

Particularly impressive was the spectacular torch-lit evening of Sunday, 31 March. Musicians from the orchestras, soldiers, students and citizens of Athens all marched across the city holding lanterns and torches, while stadium officials paraded the flags of the countries participating in the Games. The “flood of light” was enjoyed with great enthusiasm by thousands of people.

Throughout the Games, the city’s royal palaces and luxury hotels played host to high-society banquets held for athletes and other delegates of the participating countries. Among the other guests at these dinners were, of course, those foreign journalists covering this momentous sporting event that put Greece at the epicenter of international interest. In general, their reports were full of praise for the hugely successful organization of the Olympic Games and of congratulations to the city for putting on such a great show.

On 3 April (according to the old calendar), the Games concluded with the awards presentation, followed by the official closing ceremony. The spectators in attendance on that day had no way of knowing that what they were witnessing with the close of those Games was actually the start of something, not the finish. The beautiful modern Olympic adventure had begun, an adventure which has continued for 120 years and shows no signs of stopping any time soon.

Tourists share the highs and lows...

Discover five of Athens’ latest openings,...

A nexus of Hellenic research, the...

On her first ever holiday alone,...