A Summer Visit to the Acropolis: What Tourists...

Tourists share the highs and lows...

Cities need to change, to mature, never stay the same, or they die, says professor Burdett.

© Shutterstock

Athens is a complicated city. On the one hand it is densely built, with very few green spaces and the biggest ratio of car ownership in Europe. On the other, however, it is a city that has survived multiple crises and has come through today with renewed vigor, seeking to reconnect with its future.

These unique traits that define Athens have been the subject of research for the past two years by scientists at the London School of Economics together with Greek experts, who compared the characteristics of the Greek capital against those of other big cities in Europe and the world. The density of construction and habitation, free spaces, the transportation mix, its social and socioeconomic identity, how it is governed and the particular traits of its neighborhoods are among the issues that were analyzed.

The results of this two-year program, the Athens Urban Age Task Force initiative, were presented on June 16 at an open event at the Serafeio Community Complex. The presentation was also a good opportunity for a fascinating chat with Ricky Burdett, an architect and professor of urban studies at LSE and the head of the LSE Cities research center, which studies metropolises around the globe.

Burdett talked about what makes Athens special, pointed out the challenges it faces as a city and spoke in favor of radical reform in its administrative structure, with the unification of smaller municipal authorities into one big Athens Municipality, along similar lines to London.

"Athens is pretty unique: its location in the Attica Basin, surrounded by mountains and the Mediterranean Sea. And its extraordinary density," says Burdett.

© Shutterstock

What is the Urban Age program?

The program has been around for more than 15 years with the support of the Herrhausen Gesellschaft foundation. It has an intellectual and a practical side. The intellectual side, which is why we started the program, is to understand the links between the physical organization of cities and their social and environmental impacts. The last few years we realized that one of the best things we can do with our research and collective knowledge is to work with city administrators to improve knowledge exchange, around the themes of sustainable and inclusive urban development – and is the practical side of the program.

So why Athens?

Athens is a city that fascinated everyone, not only for its obvious historical reasons, but also because of its physical and socioeconomic environment. It’s pretty unique: its location in the Attica Basin, surrounded by mountains and the Mediterranean Sea. And its extraordinary density. There are not many cities so compact and so continuous. Seen from above, it is a sea of concrete with some clusters of green and brown. It is a 21st century city, a part of which is unplanned, it just happened especially after World War II. And a part of which has this Germanic grid at the heart of it. It is also a city governed in a very complex way, that in the last 15-20 years has gone through incredibly difficult times with multiple crises – economic, refugee and the pandemic. Also, when we started, the new mayor was just appointed and this created an opportunity to work and add value.

What are the elements that differentiate Athens from other European cities?

If I had to choose just one thing, it would be its extraordinary density. Athens is the second densest city in Europe after central Paris. On the other hand, it has experienced negative growth. Over the last 20 years, its population dropped slightly. If we calculate urban growth in people per hour, Athens is roughly zero, Vienna just below 2, London at 9 and Lagos (Nigeria) over 76! At the same time, Tokyo loses 10 people per hour. What does this mean? Athens is a city that is losing young people, of course it was hit hard by the economic crisis. What interested us is that one of the mayoral ambitions is to try and balance that and make the city more attractive to work and live in.

One of the greatest challenges faced by Athens is the lack of active mobility, walking and cycling.

© Shutterstock

Let’s see how the mayoral ambition turns into action…

Any mayor has a limit to the power of what he can do. For example, a mayor can attract high-tech businesses through clusters and planning. But in the end, making an economy competitive has to do with other things on a national or global relevance. In Athens, in particular, the mayor has limitations: The city only occupies a relatively small footprint of the much wider metropolitan region. The mayor of London has jurisdiction broadly over the area where people live, the transport, the police, environmental policies.

So is the city governance system in Greece inadequate and in need of reform?

The system of Athens, the four sub-regions and 35 municipalities and responsibility for transport, tourism, environment, coming from different layers, all this makes it very complicated. But you are not alone! In Paris, for example, the mayor is responsible only for 2 million people and there are discussions with the central government to rearrange regional government. Barcelona is struggling with the same issues and they invented Barcelona Regional with more powers in the metropolitan area. Athens would, over time, benefit from the restructuring of governance. Let me remind you that London has reinvented itself only since 2000. These things can be done, they require energy and recognition that a new system can deliver better services and governance.

Apart from governance, what other challenges is Athens facing?

One is clearly transport. The amount of people who use active mobility, walk and cycle in Athens is very small, only 11%, whereas in London it’s 27% and Barcelona 36%. One of the things that struck us more than anything else is the fact that Athens has the highest car ownerships: 779 out of 1,000 people own a car. Not everyone uses the car every day, but it says something about the culture and the investment in public transport.

How can a planner introduce sustainable mobility measures under those circumstances?

First of all, you need a political vision and the drive to change. None of these can be rammed down people’s throats. There has to be a recognition that the city wants to be healthier, breathe better, live longer. Then, the answer comes through a series of multilevel policies. For example, London introduced congestion tax and started pedestrianization, but permission of the local government was granted only after public transport improved by 20%. A few days ago we opened a new Crossrail line that is going to transform accessibility.

In London, the professor says, permission of the local government was granted only after public transport improved by 20%.

© Shutterstock

But a metro line takes over 20 years to build. What happens until then?

The London Crossrail took 30 years! But Paris and Milan created an extended bicycle network using the pandemic as an excuse to introduce more cycleways.

Greek municipalities were given this opportunity but almost no one took advantage of it.

‘The amount of people who use active mobility, walk and cycle in Athens is very small, only 11%, whereas in London it’s 27% and Barcelona 36%’

You first need a vision and a process of engagement, a consultation with your voters. Athens is beginning to enter this journey.

What other areas of interest are there in Athens?

The absence of green and open spaces, which contributes to the heat island effect. Having mountainous areas outside the city is an asset, access to them could be mobilized. Former industrial areas have potential, not only to become new neighborhoods but they can also act as green lungs. Elaionas is ideal for that. Also, a very important issue is housing. If you don’t invest in affordable housing, there’s no way you’ll make young people live in the city. The city authority in Athens intends to set up a housing agency.

Couldn’t this also be achieved through control of short-term rentals? I mean, no one will build 1,000 houses in Athens.

Athens could learn from Barcelona, which was very inventive in setting limits to Airbnb and hotels and at the same time accelerating growth. The relationship between the market and the public sector is an argument in favor of a Stalinist intervention or letting the market rule. The Scandinavian example shows private and public sector can cohabit effectively. Personally, I am in favor of taxing empty properties.

Is Athens’ center becoming over-touristed?

I will give you my impression, rather than a fact. I would not say that the center feels like a Disneyland for tourists. It still feels like a real, authentic city. Of course there are pockets with large numbers of tourists, but I don’t think that Athens has lost its urban character.

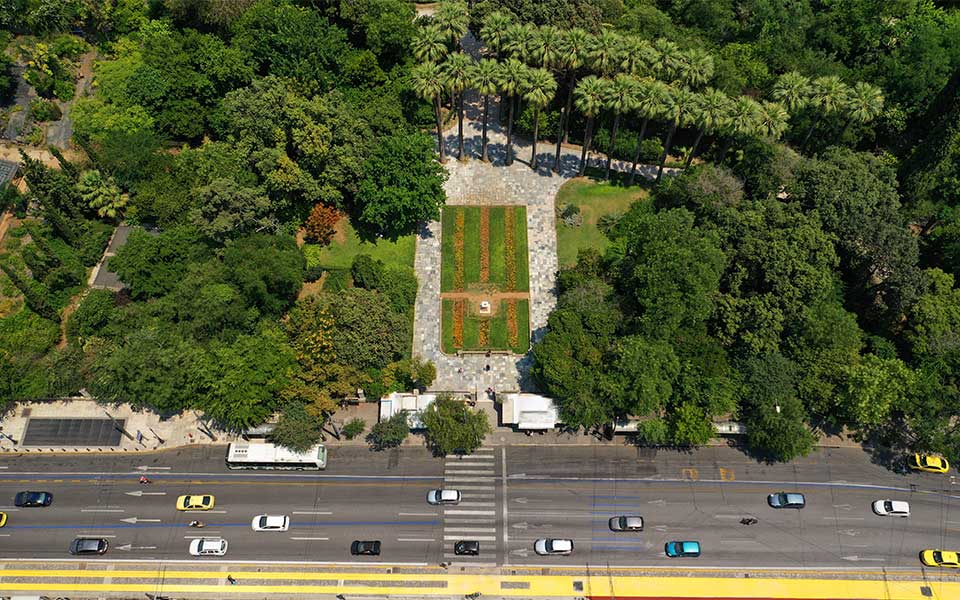

The absence of enough green and open spaces needs to become a top priority in the GReek capital, the report reveals.

© Shutterstock

An issue that still isn’t discussed much in Greece is how the real estate project to create a 10,000-inhabitant city in Elliniko will affect Athens.

I am in favor of development. Cities need to change, to mature, never stay the same, or they die. There are some issues that one needs to take into account now. Investments like that must never be considered as self-standing developments. Planning ideologies and the role of local governments can play an important part, to make sure developments like that provide assets, e.g. parks, educational infrastructure, and add something new. Also they must genuinely be connected with public transport. A talented planner needs to keep these in mind.

After your experience with the Urban Age project, how would you describe Athens?

Athens is dense both physically and within its experiences. It is a city with a strong urban character, not always pretty, but with an urban quality. You can feel the pulse.

This article was previously published at ekathimerini.com.

Tourists share the highs and lows...

Echoes from history meet everyday life...

The workshop of famed tile painter...

A guided journey across Athens’ storied...