The most illustrious Greek politician in Europe, Ioannis Kapodistrias, first Governor of Greece, was assassinated on the steps of a church in Nafplion on September 27, 1831.

As dawn broke and church bells rang out across Nafplion on that fateful day 190 years ago, Ioannis Kapodistrias, Governor of the newly-formed Greek state and one of the most gifted statesmen of the age, arose from uneasy sleep and put on his formal attire to attend Sunday mass.

Fearful of the rumours of a plot against the governor’s life, his house servants and bodyguards begged him remain at home. Ignoring their pleas, he stepped outside in the morning air and walked the empty streets to St Spyridon Church in the heart of the old city, accompanied by his faithful bodyguards Giorgios Kozonis, who had lost a hand in the recent war of independence, and Dimitrios Leonidis.

At a quiet intersection prior to arriving at the church, the three men encountered Konstantinos Mavromichalis and his nephew Georgios, briefly exchanged pleasantries, and went on their way. Moments later, outside the entrance of St Spyridon, the Governor saw the two men again, waiting on the steps.

Ioannis Kapdoistrias, First Governor of Greece (1828-1831). Portrait by Thomas Lawrence.

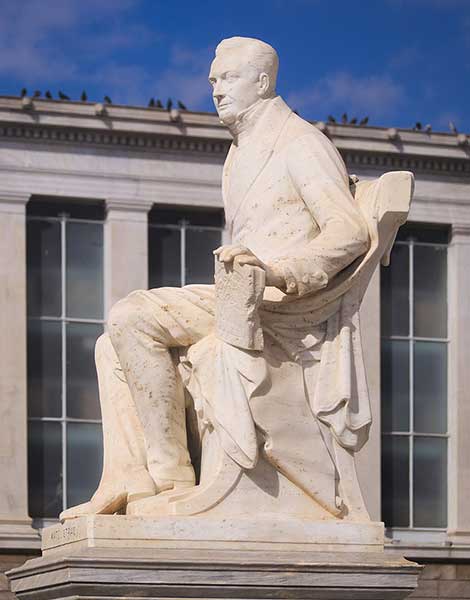

Statue of Ioannis Kapodistrias (by Georgios Bonanos) in Panepistimiou Street, in front of the National and Kapodistrian University, Athens.

Ioannis Kapodistrias was born on February 11, 1776, on the island of Corfu, the son of an aristocratic Corfiote family of distant Slovenian and Greek-Cypriot descent. Fighting alongside the ruling Venetians, his ancestors had distinguished themselves in the wars against the Ottoman Turks and been rewarded with the title of nobility.

Kapodistrias studied medicine, philosophy and law at the University of Padua, returning to his native Corfu to work as a physician and surgeon just as the Ionian islands fell to Napoleon Bonaparte in 1797. Caught up in the ensuing turmoil, the young doctor was soon appointed chief medical director of the military hospital.

French occupation was short lived. A Russian and Ottoman coalition drove out the French forces two years later in 1799 and established the Septinsular Republic, a largely free and independent state made up of the seven Ionian islands, ruled by its nobles. Thus, at the age of 25, Kapodistrias entered the world of politics and quickly rose to be Chief Minister of State, overseeing a raft of changes that brought about a more liberal and democratic constitution.

The energetic and progressive statesman soon caught the eye of the Russian diplomatic service of Czar Alexander I. Invited to St Petersburg in 1808, Kapodistrias entered the service as State Councillor. In the years that followed, he distinguished himself with a series of brilliant diplomatic successes, including Swiss unity and independence at the Paris Conventions following the fall of Napoleon, and settling critical issues at the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

Kapodistrias and the Greek struggle for independence

Greatly esteemed by diplomats and politicians across Europe for his deft handling of difficult negotiations, Kapodistrias worked tirelessly to garner support for the Greek uprising against Ottoman rule. Despite Russia breaking off diplomatic relations with Turkey in 1821, he failed in his attempts to obtain active support from the Czar.

Taking a leave of absence, Kapodistrias relocated to Geneva where he organized material and moral support for the revolution, touring Europe in the process.

In April 1827, the newly-formed Greek National Assembly elected him as the first head of state. Landing in Nafplion on January 7, 1828, it was the first time Kapodistrias had set foot on mainland Greek soil. Coming ashore to great fanfare, the country was still in turmoil. Fighting continued against the Ottomans, factional conflicts had resulted in two civil wars, and the National Assembly was unable to form a united national government. To make matters worse, the country was bankrupt.

Konstantinos Mavromichalis, brother of the Bey of Mani, Petros Mavromichalis, and one of Kapodistrias' assassins.

Georgios Mavromichalis, son of Petros, was the other assassin.

To restore order and control, Kapodistrias declared the foundation of the Hellenic State and re-established military unity by appointing Sir Richard Church (British Army officer), Demetrios Ypsilantis (Imperial Russian Army) and his brother Augustinos Kapodistrias, as joint commanders-in-chief.

Not satisfied with the terms of the first London Protocol, which limited the Greek state to the Peloponnese and Cycladic islands, Kapodistrias instructed his generals to pursue the fighting in central Greece to increase and widen its borders. Thanks to his intense diplomatic efforts, Greece was recognised as an independent, sovereign state on February 3, 1830, but there was still a long way to go before securing civil society after 400 years of Ottoman rule.

Laying the foundations for a judicial and public administration system and boosting agriculture, the economy nevertheless remained weak, and he was unable to adequately compensate the merchant families of Hydra, Spetses and Psara for their support in the war. He soon alienated many former leaders of the Revolution who wished to have more of a say in state matters. Local rulers, especially in the semi-autonomous Mani Peninsula of the southern Peloponnese, refused to give up their power and privileges to the nascent central government, inciting open rebellion against Kapodistrias.

Animosity was fuelled following the arrest of Petrobey Mavromichalis, Bey (chieftain) of the Mani Peninsula and a popular and successful leader in the uprising against the Turks. This action proved to be his undoing.

Assassination

Waiting on the steps outside St Spyridon Church on the morning of September 27, 1831, Petrobey’s brother Konstantinos and son Georgios approached Kapodistrias as if to greet him. Suddenly drawing a pistol, Konstantinos took aim at the Governor, fired, and missed, the bullet lodging in the wall of the church (where it can still be viewed today). Georgios then plunged his dagger into Kapodistrias’s chest while his accomplice reloaded and shot the Governor in the head at point blank range.

At 55 years of age, Ioannis Kapodistrias, the most esteemed Greek-born politician of the age, was dead.

St Spyridon church in Nafplion, murder site of Kapodistrias.

Kapodistrias' grave at the Platytera monastery of Corfu. To the right is the grave of his brother Augustinos.

After Kapodistrias’ murder, Greece soon descended into chaos. He was succeeded by his brother Augustinos, who resigned six months later, plunging Greece into civil strife and confusion.

Swiss banker, diplomat and philhellene Jean Gabriel Eynard wrote at the time: “He who murdered Kapodistrias murdered his homeland. His death is a disaster for Greece and a misfortune for Europe.”

The Great Powers of Britain, France and Russia convened in London and resolved to take matters into their own hands. Fearful of a republican movement that might echo the Reign of Terror following the French Revolution, on May 8, 1832, installed a monarchy, appointing 17-year-old German Prince Otto to the throne of the newly founded Kingdom of Greece.

Following his skilful handling of the creation of Switzerland, some historians have argued that Kapodistrias, had he lived, could have gone on to create a similar state for modern Greece, healing the wounds of the decade-long struggle for independence, and setting the country on a very different path.