30 Wineries Across Greece to Explore (Map Included)

Discover Greece’s winemaking heritage with tastings,...

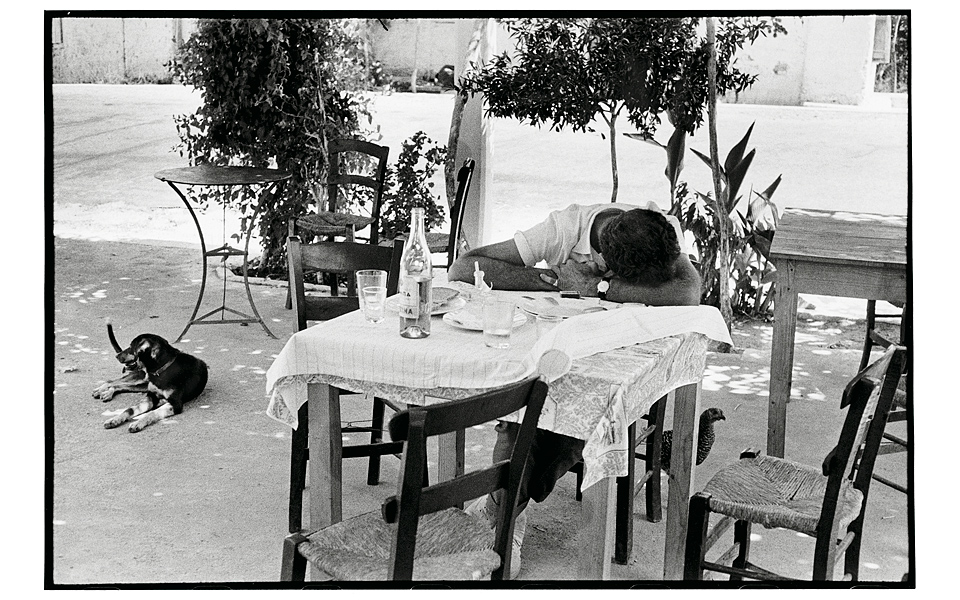

The four-legged guard keeps watch; making sure that no one disturbs his friend, bent over the table by wine-induced melancholy.

© Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Wine loses its allure when it becomes an end in itself. That is, when you drink alone, getting drunk because of addiction or to drown your sorrow, wine is bereft of its magic. This is why, for many years, millennia in fact, wine has been closely associated with good friends. Its solitary use entails an absence of measure, since there is no companion or fellow drinker present. There is no one there to share the table’s delicacies with you, or even more importantly to experience how words and feelings from a certain point on, when caught in the throes of exhilaration, can spill out into song. This is why Homer, in response to Hesiod’s query, described a festive gathering of friends as the sweetest balm for the human soul. It matters little that these two paragons of poetry, Homer and Hesiod, never actually met in the time-frame of history.

In the space-time dimensions offered to us by literature’s imaginative lens, however, they not only met, but even crossed literary swords. This took place at Chalkis, in Euboea, where the two epicists competed for the first prize in poetry awarded during the funeral games of King Amphidamas.

All this can be found in the eminently charming and simultaneously instructive one-of-a-kind narrative titled The Contest of Homer and Hesiod, which goes back to the 5th century BC and was often taught to students of that period and through the ages. In the narrative, Hesiod asks what is most edifying for the human soul. In response, Homer, he who turned war and errant adventure into story, replied as follows, without hesitation and in a manner that his “opponent” must surely have envied:

When mirth reigns throughout the town And feasters about the house, sitting in order Listen to a minstrel; When the tables beside them are laden with bread and meat And a wine bearer draws sweet drink from the mixing-bowl and fills the cups: This I think in my heart to be most delightsome.

“…Homer, in response to Hesiod’s query, described a festive gathering of friends as the sweetest balm for the human soul.”

“Wine, moreover, makes an excellent companion to songs of sadness; at funerary banquets in the memory of a loved one, whose glass remains empty.”

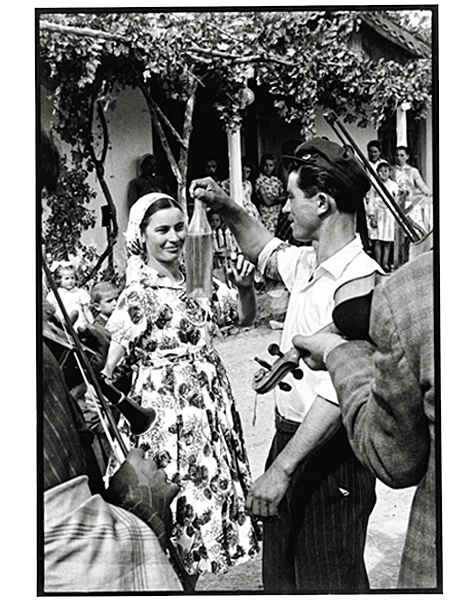

Even those familiar only with his name, must, out of intuition alone, agree with Homer’s incisive reply if they’re even marginally acquainted with the delights afforded by such a banquet. The feeling is equally rich, no matter the reason for gathering family and friends around the table and, later, around the dance floor: weddings or christenings, Easter, the feast of the Assumption, or a local holiday in the humblest of churches. With one serious caveat pertaining to the intrusion of contemporary technology: video cameras ought to be banned, for they choreograph and therefore falsify our spontaneity; as well as, it goes without saying, the taking of selfies, which interrupts the natural tempo of merry-making.

Wine, moreover, makes an excellent companion to songs of sadness; at funerary banquets in the memory of a loved one, whose glass remains empty. There’s an incredibly stirring Klepht folk song, which was first published by Claude Fauriel in Paris between 1824 and 1825, and translated almost immediately into German by the accomplished poet and passionate philhellene Wilhelm Muller. There, the badly wounded Captain Iotis, to console both himself and his men, asks for wine as he lies dying:

Oh, help me up my trusted men and prop me up to sit That I may get drunk on sweet wine that you bring to my lip And sing sad songs, oh, songs of woe For what to say before I go? This wound is venom in my side, The lead a bitter way to die.

An another folk song – this one concerning love – we find out how the wine lover would prefer to be buried so as to experience eternal delight.

If I die for wine, Bury me in the tavern. That I may be stepped upon by the clientele, And the beautiful girl who treated me.

In Greece, the art of wine is age-old, and twofold. On the one hand, there is the art of its preparation, which is of the highest standard, with many cities vying for pre-eminence. While on the other, there is the art of consumption, in which wine figures as the defining component of sociability, an irreplaceable companion to life’s meaningful moments, both private and public: celebration and mourning, war and peace.

To further deepen and elaborate on the art of consumption, ancient Greek poets and philosophers – including some of the most prominent – studied the social experience of drinking – no doubt over a tipple. They thought up laudatory verses and proposals as to the most effective ratio of water to wine, depending on whether the aim is to prompt discussion or revelry. They devised pithy aphorisms about wine drinking as an effective yet temporary means of escape from this world’s soul-destroying burdens. And they were well aware of the risks of drinking in excess, which can reveal a person’s deeply hidden inner truth.

Violins, clarinet, dance, modest smiles, and two gazes meeting over a glass of wine. Shyness as naturalness.

© Constantine Manos/Magnum Photos

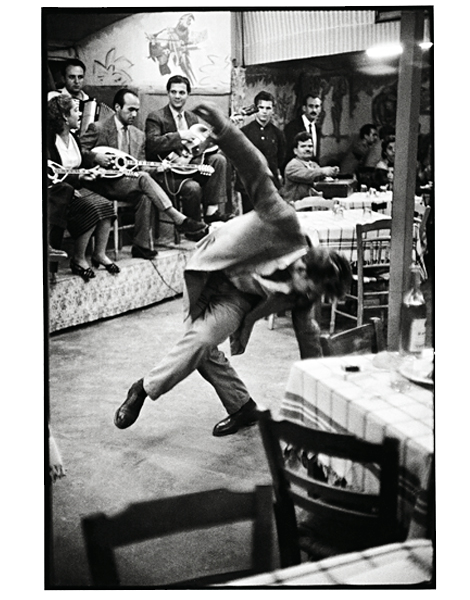

Almost like Antaeus. He stoops and respectfully touches the ground to receive the necessary strength that will raise him up. The zeibekiko, without any fancy footwork, remains the most contemplative dance.

© Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Homer, Hesiod, and Aeschylus – who, according to hearsay “wrote his tragedies while under the influence,” which is why Sophocles condemned him, even though the latter choked to death, somewhat ironically, on an unripe grape – all three deemed wine and the banquet-symposium worthy of the same respect they bestowed on the theater or the Ekklesia (popular assembly). In this they were by no means alone: for so too did Anacreon, Theognis, Euripides, Aristophanes, as well as Xenophanes of Colophon, Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch, and so many others. The Deipnosophists by Athenaeus, an author from Nafkratis in Egypt who lived around AD 200, is a concise encyclopedia of winemaking laced with dense poetic and philosophical trivia about how we drink, why we drink, and with whom we ought to drink.

Indeed, it is at the very crossroads of “Oinos/Wine” that we find the place where ancient Hellenism and Christianity mingled in the most benign, peaceful and fertile of ways. Ancient Greek “paganism” lauded Dionysus for his glorious gifts to the world – vineyards and wine – for they provided a temporary release from life’s cares and the woes of death. It is precisely this point that allowed for the rapid reconciliation with Christianity, whose founder, Jesus Christ, launched his miraculous works at the wedding at Cana by turning water into wine. Later he described himself as the “new vine,” “the true vine,” and, finally, at the Last Supper, he offered up wine as “the new covenant in my blood.”

It was this very syncretism that the poet Angelos Sikelianos eulogized by honoring “The Crucified Bacchus” and “Dionyso-Jesus” in his poems. An imperceptible thread of common vocabulary, symbols, and corresponding mindset weaves together – certainly not directly and despite sporadic gaps – the seer Tiresias’ description of Dionysus in Euripides’ Bacchae as he who “gives to mortals the vine that puts an end to grief” with the “unsorrowful wine” brewed by the monk Alypios in Alexandros Papadiamantis’ tale The Black Stumps.

The power of wine to soothe a variety of ills is enshrined in our demotic folksongs. First and foremost, of course, it allows one to forget, albeit temporarily, the pain of thwarted love. We see it here in the following distich, still sung throughout Greece:

I never got drunk, tasted neither raki nor wine, But now I drink them both to drive you from my mind.

Indeed, it is at the very crossroads of “Oinos/Wine” that we find the place where ancient Hellenism and Christianity mingled in the most benign, peaceful and fertile of ways

“The belief in the power of wine to embolden the warrior comes down to us, once again, from Homer.”

What is more, it distracts you from the debts that hound you. This is conveyed in a widely known and beautiful ballad, The Return of the Exile. A man returns from abroad, and, completely changed by years spent away from his home, has to offer his wary and suspicious wife persuasive proof of his identity. Instead of telling her about certain marks on her body that only he could possibly know of, he decides to describe her garden:

You have an apple tree at the entrance / and a vine in your yard / Laden with rosaki grapes that make a wine as sweet as honey, / When the poor drink of it their debts are driven from their mind / When the janissaries drink from it, / they leave for war without a care.

The belief in the power of wine to embolden the warrior comes down to us, once again, from Homer. In the Odyssey, the father of poetry refers to wine as “manly virtue” to establish precisely how it stokes courage.

There is, however, a form of intoxication that eclipses the drunkenness caused by wine: that of two lovers exchanging kisses. Again, we hear this mentioned in a folksong, and more specifically in a Cretan mantinada (sung narrative) memorialized by the prose writer Ioannis Kondylakis:

Whoever kisses your red cheek / Will find himself in a fever / No need for wine, or draught of raki.

We hear it, too, in the Song of Songs attributed to Solomon. In it, kisses and the embrace of a loved one are celebrated as more intoxicating than wine itself: “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth for your breasts are better than wine.”

Eros and wine, Aphrodite and Dionysus. This is the heady farrago of our link to the Ancients, and a forerunner of all today’s cocktails.

Discover Greece’s winemaking heritage with tastings,...

A Polish-born artist who lives on...

Why not try a brief getaway...

From fishermen’s chants to moonlit serenades,...