The great shadow Aristotle cast through his insatiable intellect, meticulous observations and prolific legacy of textual material continues to hang over Halkidiki, especially its eastern coast, where he was born and raised – at Stageira. The product of a well-connected Stageirite family, Aristotle suffered the loss of both his parents by the age of ten and received much of his early education from his guardian. He moved to Athens to attend Plato’s Academy and went on to become a teacher, a profession that led him to Assos in Aeolia (western Asia Minor), Mytilene (Lesbos), Pella (the Macedonian capital), back to Athens and finally to Chalcis (Euboea). However, Aristotle was more than just a teacher. In formulating his inductive-deductive scientific method of Analysis, Aristotle laid the groundwork for modern science, and was in fact the first example of what we would recognize today as a “university professor.” He essentially shaped how scholars have been thinking and expressing themselves – logically and persuasively – for more than 2,300 years. In the early 14th century, Dante Alighieri referred to Aristotle in his Divine Comedy as “The Master of Those Who Know.” What’s more, he lived in momentous times and moved in high circles, often rubbing shoulders with other key historical figures of his day.

Son of a Doctor

Aristotle’s hometown, Stageira, was originally a colony of Andros, located in a region, Halkidiki, that had been settled by people from Chalcis. Aristotle himself was a true native son, representing both of these founding ancestral lines: his father was a local Stageirite while his mother hailed from a landowning Chalcidean family in Euboea. Aristotle’s education likely began with training in medicine from his father, Nicomachus, who served as court physician to Macedonia’s King Amyntas III. The art of medicine was then a profession closely guarded by its practitioners, handed down from father to son. Unfortunately, Aristotle’s parents died while he was still young and an uncle or family friend, Proxenus of Atarneus, brought him up, providing lessons in Greek, rhetoric, poetry and probably composition.

Philosophy, Politics and Strange Creatures

In 367 BC, Aristotle traveled to Athens to begin studies under Plato at the Academy. Aristotle was greatly influenced by his respected teacher, shaping his initial views after those of his mentor. Over time, however, he developed his own views on the many subjects (collectively considered “philosophy”) that he studied and taught. During his two decades in Athens, Aristotle’s intellectual interests spanned the arts and sciences and it was at this time that he began to develop his ordered and logical approach to supporting one’s own philosophical or scientific arguments and disputing those of others.

“In the early 14th century, Dante Alighieri referred to Aristotle in his Divine Comedy as “The Master of Those Who Know.” ”

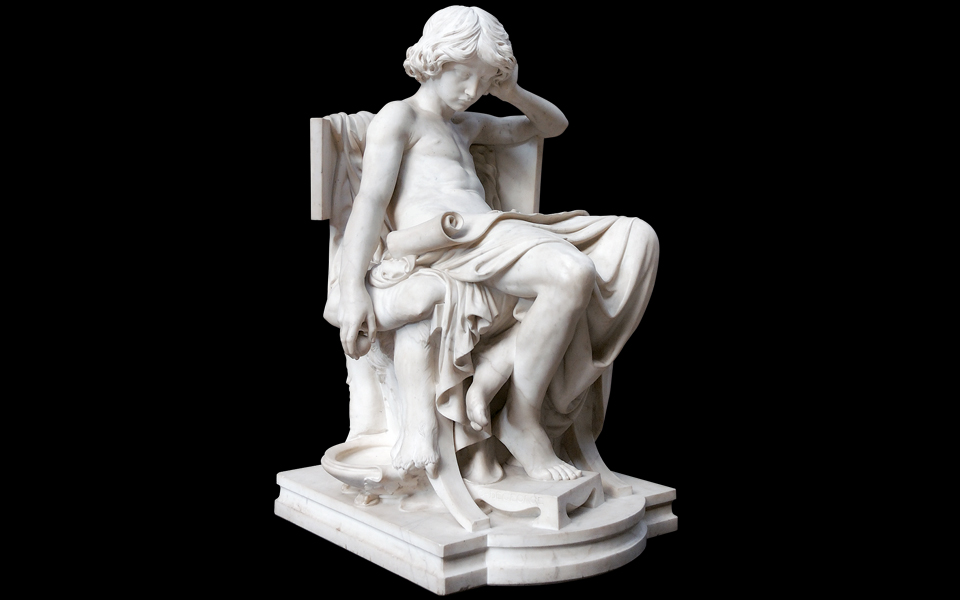

© Courtesy of Musée d’Orsay, Paris

“His extraordinary powers of observation, together with those of the fishermen and other sharp-eyed informants or collaborators he relied on, led to the classification of more than 500 species.”

Aristotle’s writings, although less elegant than Plato’s, were more systematic. Ultimately, he also diverged from Plato with regard to politics. While his aristocratic, conservative teacher condemned Athens’ extreme form of democracy, Aristotle, more a man of the people, cautiously approved of the Athenians’ progressive idea of rule through majority decision-making. Aristotle eventually departed Athens, accompanied by his friends Theophrastus (the future “father of botany”) and Xenocrates. They sailed northeast to Assos, where Aristotle assumed the leadership of a circle of philosophers assembled there by another old Academy friend, Hermias of Atarneus, now the city’s ruler. Aristotle spent the next four years — first at Assos, then on the island of Lesbos across the water — conducting fundamental scientific research, especially in zoology and biology, which remained unsurpassed for the next two millennia. His extraordinary powers of observation, together with those of the fishermen and other sharp-eyed informants or collaborators he relied on, led to the classification of more than 500 (often minutely described) species. Two intriguing creatures that Aristotle closely documented were the octopus and the Black Goby, a small fish local to Lesbos and surrounding waters. The investigator’s description of the octopus’ lengthy, vine-like, sperm-delivering hectocotyl arm and his accurate suppositions about the male goby’s highly peculiar mating habits and secondary sexual characteristics were long considered incredible and had to wait until the 19th and 20th centuries to be confirmed by modern science.

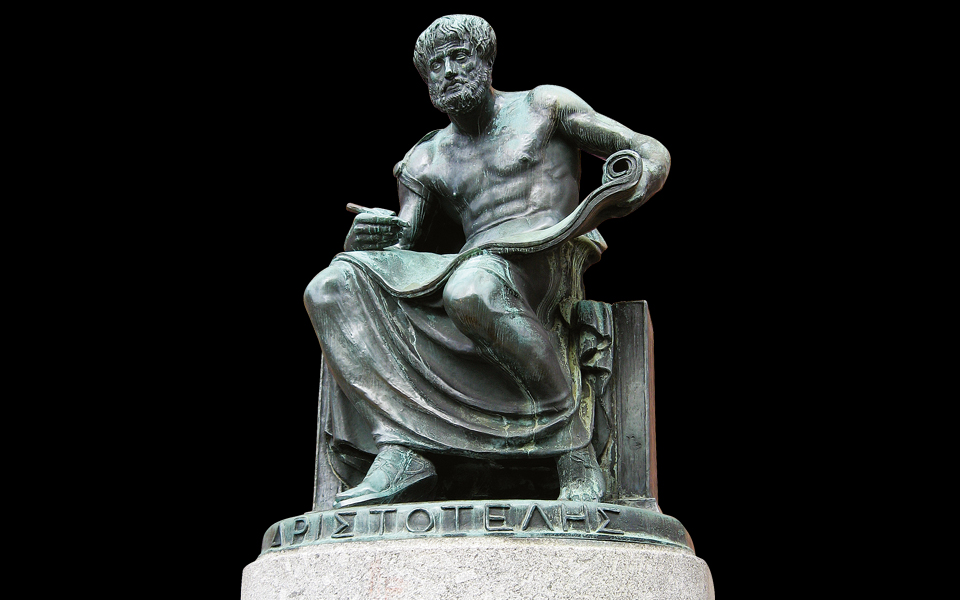

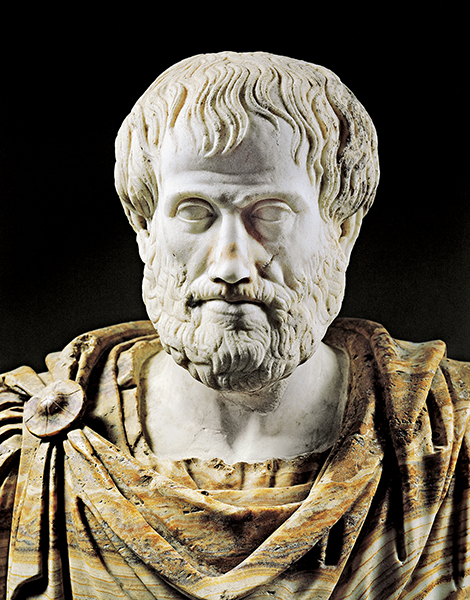

© Courtesy of Vatican Museum, Rome

© Courtesy of University of Glasgow

A Royal Tutor

In Pella, the boy who would become Alexander the Great was reaching adolescence, and his father must have decided that Aristotle would be useful in shaping his son’s young mind. The philosopher was summoned to the Macedonian capital in 343 BC, where he took over Alexander’s education, tutoring him (and, if tradition holds true), other prominent sons at the shady, riverside cave complex at Mieza. A small L-shaped stoa (colonnaded, roofed walkway) once stood against the cliff face at the picturesque rural site (Veria-Naoussa-Edessa region), known today as the School of Aristotle. Aristotle fed Alexander’s omnivorous curiosity for knowledge, giving him instruction in Homeric literature, philosophy, morals, religion, logic, art, geometry, astronomy, rhetoric and medicine. The future king’s appreciation for learning was apparent again after 334 BC, when, on his Asian campaign, he included in his entourage a team of zoologists, botanists and other scientists. Prior to his departure for Persia, Alexander seems to have found another role for Aristotle, sending him back to Athens in 335 BC to establish a rival school of philosophy: the Lyceum. Over the next dozen years, Aristotle lectured repeatedly on a vast range of subjects – augmented and refined since his last tenure in Athens – including astronomy, biology, botany, chemistry, ethics, history, logic, metaphysics, meteorology, philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, physics, poetics, political theory, psychology, rhetoric and zoology. While is old alma mater the Academy maintained a relatively narrow scope, the Lyceum offered a broader view – more like a modern “university” – focusing especially on Aristotle’s favorite pursuit: the detailed examination of nature.

“Prior to his departure for Persia, Alexander seems to have found another role for Aristotle, sending him back to Athens in 335 BC to establish a rival school of philosophy: the Lyceum. ”

© Courtesy of University of Freiburg

“He disagreed with Plato that application of reason was most important, instead suggesting a scientific method within which both logic and especially observation are essential.”

Death and Legacy

After Alexander’s demise in 323 BC, Athens again became uncomfortable for Aristotle. The following year, with the example of Socrates in mind, he is said to have departed the city at his own choosing, wishing to save Athens from twice sinning against philosophy. He retired to Chalcis, where he soon passed away at age 62 from a stomach ailment – leaving all his papers and his vast scholarly library to Theophrastus, his successor at the Lyceum. Eventually, when Athens was overrun and looted in 86 BC by the Roman general Sulla, Aristotle’s writings were carried back to Rome, where, in 60 BC, they received their first collation, titles and commentary from Andronicus of Rhodes. Aristotle’s surviving works, although perhaps only one-fifth of his total output, still amount to about one million words; the most important texts include Physics, Metaphysics, Nicomachean Ethics, Politics, De Anima (On the Soul) and Poetics.

Aristotle also invented the field of logic (“analytics”), pioneered zoology – both observational and theoretical – and systematically defined many other academic disciplines. He divided the sciences into three categories: productive (those offering products, such as engineering, architecture and rhetoric); practical (those guiding behavior, such as ethics and politics); and theoretical (those seeking information and understanding for their own sake, such as pure mathematics and what we know today as philosophy). Aristotle believed science must be approached logically. He demonstrated inductive and deductive reasoning in his now-famous syllogism: “A = B, B = C, A = C” or, as he also put it, “Every Greek is human; every human is mortal; therefore, every Greek is mortal.” He disagreed with Plato that application of reason was most important, instead suggesting a scientific method within which both logic and especially observation are essential. In this way, he fostered the birth of empirical science.

© Courtesy of National Archaeological Museum, Naples

© Getty Images / Ideal Images

Aristotle particularly excelled as a philosopher on ethics and politics. On happiness, he wrote that a good life is the philosophical life, the political life and the voluptuary (pleasure-loving) life. On virtue, he argued that there are two kinds: moral and intellectual. Virtues are states of character that find expression in both good purpose and moderate action. Aristotle condemned the lending of money for profit (“most unnatural”); refused to condemn slavery as a whole; used the term “democracy” to signify anarchic mob rule; and suggested (quite meaningfully for our own cybernetic age) that despite being mortal, human beings should seek to make themselves as immortal as possible. He similarly seems to anticipate the invention of robots when he comments that if nonliving machines could be constructed to carry out everyday tasks, slaves would no longer be needed as living tools. In myriad ways, Aristotle was a man far ahead of his time. As an observer of human nature, he was sympathetic to the strengths, weaknesses and popular tastes that we account as common today.

On drama, he noted that imitation is something natural and educational, familiar from childhood; by viewing theatrical tragedies, one can experience a catharsis of one’s own sorrows and anxieties. Although Aristotle was a devoted thinker who must have required solitude, he also greatly appreciated his happy family life—involving a daughter and a son, by different mothers—from which some of his astute observations on behavior may have stemmed. He valued as well the company of his professional colleagues, surrounding himself wherever he went with a circle of collaborating scholars. Later biographers characterize him as kindly and affectionate, yet with a biting wit, considerate to his family and servants but possessing many enemies and perceived by them as arrogant and overbearing.

Above all, Aristotle was an accomplished speaker, a persuasive, well-spoken lecturer, a passionate teacher and a disseminator of knowledge, who, unlike his counterparts at the club-like Academy, opened the Lyceum to the general public to freely attend philosophical and scientific talks. As the world’s first research scientist, he made mistakes – such as placing the Earth at the center of the Universe – but he readily admitted ignorance when evidence was lacking. What he most trusted and emphasized was observed phenomena. Yet he is perhaps best remembered and most relevant for his essential, over-arching ideas that address such eternal concepts as place, time, causation, and determinism. As one of today’s great philosopher-historians, Sir Anthony J.P. Kenny, recalls, Aristotle once claimed that everyone must do philosophy, because even arguing against the practice of philosophy is itself a form of philosophizing.

“He similarly seems to anticipate the invention of robots when he comments that if nonliving machines could be constructed to carry out everyday tasks, slaves would no longer be needed as living tools.”