Lord Byron summed up the rise and fall of classical Greece in his epic poem “Greece Enslaved” of 1812: “Fair Greece! sad relic of departed worth! Immortal, though no more! though fallen, great!”

In the early 21st century, as an ongoing economic crisis immiserates millions of Greeks and threatens the financial stability of Europe, those questions are more important than ever – and they can be answered. As we can now show, the ancient Greek cultural accomplishment was underpinned by robust and sustained economic growth, made possible in turn by a distinctive approach to politics.

The Greek economy reached its premodern peak in ca. 300 BC. It was not until the 20th century that the number of people living in the Greek core and their material welfare returned to levels comparable to those achieved some 2,300 years before (see graph: “The Development Index”).

The ancient Greek economic rise was exceptional in world history for its duration, intensity and long-term impact on world culture. It took place in a social ecology of hundreds of city-states. While wealth and incomes remained unequal in those communities – there were slaves in the most prosperous of the Greek states – many Greeks experienced prosperity. The growth of the economy was driven by an extensive middle class of people who consumed goods and services at a level far above subsistence.

CITY-STATE ECOLOGY

By the later 4th century BC, when Aristotle was writing his masterpiece on Politics, there were about 1,100 Greek city-states, or poleis. They stretched from outposts in Spain and France through southern Italy and Sicily, to the shores of the Black Sea and western Anatolia and south to eastern and southern outposts in Syria and North Africa. The total population of Hellas – that is, the residents of small states that were substantially Greek in language and culture – was over 8 million; about a third of them lived in “urban” areas (towns of more than 5,000 people). They inhabited large and well-built houses, lived relatively long lives and produced and consumed very substantial quantities of high-quality goods.

In an inversion of the experience of Europe from 1500 to 1900 or China from circa 700 to 200 BC, where systems of small states fell to the centralizing logics of state-building and empire, there were many more independent states in the Greek ecology at the height of the classical era than there had been several hundred years previously. Moreover, many of them were organized as democracies. Ancient Greek history points to an alternative to the dominant narrative of political and economic development, which, based primarily on the history of early modern Europe, calls for first big, centralized and autocratic states, and only then (sometimes) democracy and wealth.

THE COMPETITION CYCLE

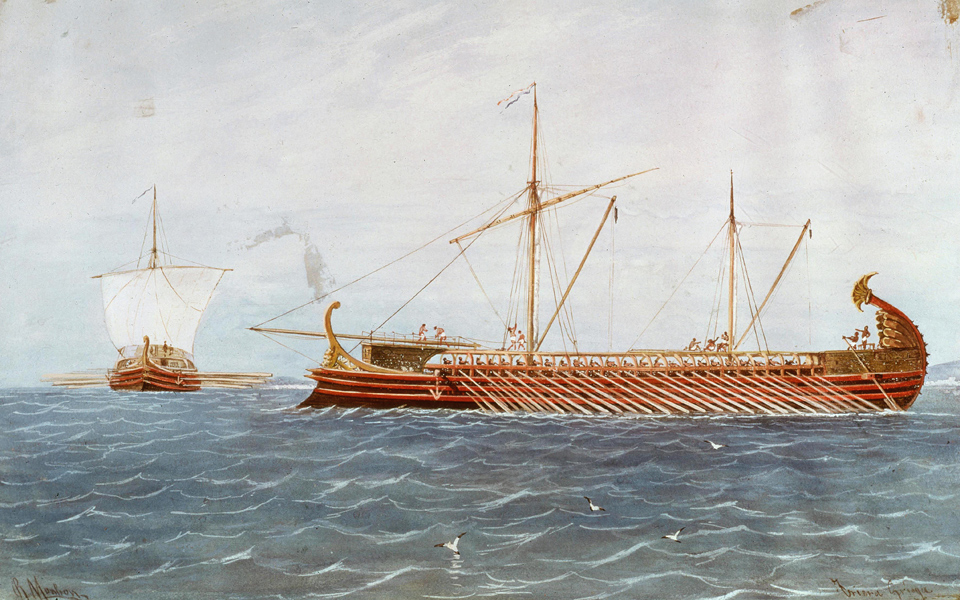

The key to unlocking the puzzling success of the Greek city-state ecology is economic specialization and exchange. Individual Greek states developed specialties based on natural resource endowments relative to other poleis. The Aegean island-state of Paros focused on the fine white marble found there, while the cities of southern Italy and Sicily focused on its favorable wheat-growing conditions. Other poleis developed advantages by perfecting industrial processes, as Athens did with its manufacturing of painted vases and warships. Competition and conflict among poleis served to sharpen the recognition that it was necessary to exploit comparative advantages. The Greeks also recognized the value of lowering transaction costs, which encouraged open access and inter-state cooperation.

The upshot of the cycle of competition, specialization and cooperation was a high premium on innovation and entrepreneurship. Innovation in turn drove a dynamic that Joseph Schumpeter famously described as “creative destruction”: Advances in artistic and productive techniques drove out earlier techniques; new institutions marginalized traditional forms of social organization; poleis that exploited relative advantages absorbed their less innovative rivals, while new poleis were continuously being created on the ever-expanding frontiers of Hellas.

“ By sharply contrasting the fortunes of ancient and modern Greece, Byron’s couplet poses two questions that have long puzzled historians: How did the ancient Greeks gain the wealth with which to build a culture that became central to the modern world? And if Greece had once been prosperous, why was it no longer? ”

© www.visualhellas.gr

The products of local specialization were readily distributed within poleis, across the extensive small-state ecology and then beyond the Greek world through increasingly dense networks. Local markets grew into regional markets, and some poleis succeeded in creating major inter-state emporia where goods from across the Mediterranean and Black Sea worlds could be bought and sold. Experts in various arts and crafts migrated to new homes and established new centers of specialized production.

Meanwhile, the costs of transactions were driven down by continuous institutional innovations, notably by the development and rapid spread of silver coinage as a reliable exchange medium; the dissemination of common standards for weights and measures; the creation of market regulations and officials to enforce them; and increasingly sophisticated systems of law and legal mechanisms for dispute resolution.

Competition and conflict between poleis and between the Greeks and their non-Greek neighbors temporarily disrupted local networks of exchange. But those disruptions only served to motivate poleis and individuals to seek out new markets for their goods and services, to deepen and broaden their exchange networks, and to develop cooperative solutions whereby conflict could be reduced or at least rendered less disruptive.

“ Experts in various arts and crafts migrated to new homes and established new centers of specialized production. ”

CREATIVE DESTRUCTION

To explain the rise of Hellas, we need to answer why and how specialization and exchange in the Greek world became so strongly intertwined with continuous innovation and creative destruction – thereby driving a sustained level of economic growth. The answer is good political institutions. The institutions found in many citizen-centered Greek states – but especially in democratic Athens – put specialization and innovation in overdrive. Greeks willingly invested in their own education and took the risks of entrepreneurship because they knew that they had legal recourse if and when a powerful individual or corrupt official tried to steal their profits.

Today, we typically think of such protections as “rights.” The Greeks developed a strong tradition of civic rights – immunities against arbitrary action by powerful individuals or government agents. These immunities guaranteed each citizen the security of his body against assault, the security of his dignity against humiliation and the security of his property against confiscation. It is important to remember that many residents of a polis were not citizens, and so they were not full participants in the regime of immunity and security. And yet, in some of the most highly developed poleis, these immunities were extended to at least some non-citizens.

NEW APPROACH TO POLITICS

Citizens collectively held the authority to make new institutional rules, and as a result, they were more likely to trust the rules under which they lived to be basically fair. Judgments, by citizens who were empowered (by vote or lottery) to settle disputes and to distribute public goods, were made on the basis of established and impartial rules, rather than on the basis of patronage or personal favoritism. With these guarantees in place and successful innovation well rewarded, individuals had strong incentives to invest in their own special talents, to defer short-term payoffs and to accept a certain level of risk in anticipation of long-term rewards. The end result was a historically unusual level of sustained economic growth and an equally unusual rate of sustained cultural productivity and innovation.

The historically distinctive Greek approach to citizenship and political order was the key differentiator that made the Greek efflorescence distinctive in premodern history. It drove specialization and continuous innovation through the establishment of civic rights, aligned the interests of a large class of people who ruled and were ruled over in turn, and encouraged the free exchange of information. The emergence of a new approach to politics is what propelled Hellas to the heights of accomplishment celebrated by Lord Byron.

Among the most notable products of Greek specialization were new forms of expertise, notably in warfare and state finance. While developed within a civic context to further the purposes of Greek city-states as civic communities, military and financial expertise proved to be readily exportable. Relevant forms of expertise migrated across the borders between poleis – but also to emerging states at the frontiers of the Greek world. Macedon was the most successful of those emerging states.

King Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great conjoined Greek expertise in finance and warfare with ethno-nationalism and rich natural resource endowments. The result was the emergence of state capacity that was unequalled in the prior history of the Mediterranean world: In the course of a generation, Macedon conquered not only the poleis of mainland Greece, but also the vast Persian Empire. Although the classical era was ended by the Macedonian conquest, the Greek economic and cultural efflorescence continued. The Hellenistic kings allowed considerable independence to the city-states and taxed them at moderate rates. Democracy became even more prevalent, public building boomed and science and culture were codified and advanced. The perpetuation of prosperity in the Hellenistic era made possible the “immortality” of Greek culture: Greek culture was codified and was so widely dispersed that enough of it survived for Lord Byron to admire – and for us to explain what made it possible.

“ Judgments, by citizens who were empowered (by vote or lottery) to settle disputes and to distribute public goods, were made on the basis of established and impartial rules, rather than on the basis of patronage or personal favoritism. ”