The Panathenaic Way: Athens’ Historic Pathway Comes Alive...

A major restoration project is bringing...

Panathenaic amphora, a victory prize from ca. 530 BC depicting a foot race, attributed to the painter Euphiletos. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

© Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece/Kapon Editions Courtesy

The Olympic Games of AD 165 ended horribly. Not far from the main stadium, watched by a large crowd, an old man called Peregrinus Proteus – an ex-Christian convert turned loud-mouthed pagan philosopher and religious guru – jumped onto a blazing pyre to his death. This self-immolation was modelled on the mythical death of Herakles (one of the legendary founders of the Games) and was meant as a gesture of protest at the corrupt wealth of the human world, as well as a lesson to the guru’s followers in how to endure suffering. In fact, Peregrinus kept putting off the final moment. It was not until the Games had officially finished, that he built the pyre and took the plunge. But there was still a big audience left to witness his death, because traffic congestion (too many people trying to leave the place at once), combined with a shortage of public transport, had prevented most people from leaving Olympia. Then as now, presumably, only the VIPs were whisked away.

The story of Peregrinus is told by an eye-witness, the ancient essayist Lucian – who not only describes the old man’s last moments, but also throws in the point about the ancient Olympic traffic problems. Lucian himself has no time for Peregrinus: “a drivelling old fool” bent on “notoriety,” he sneered. But the story is not a sign of the decline of the Olympics under Roman rule. It was because the Games were still such a major attraction that Peregrinus chose the occasion for his histrionic suicide; and it was because of their considerable cultural significance that the incident was so prominently written up.

When we now think back to the ancient ancestors of the modern Olympics, we usually bypass the Roman period, and concentrate instead on the glory days of Classical Greece. It’s easy to ignore the fact that the ancient Games were “Roman” for almost as long as they were “Greek” – in the sense that they were celebrated under Roman rule and sponsorship from the middle of the 2nd century BC until they were abolished by Christian emperors at the end of the 4th century AD. In most modern accounts, the true ancestor of “our” Games lies in the rose-tinted age of Classical Greece, between the 6th and 4th century BC, or maybe even further back (according to legend the ancient Games were founded in 776BC, though not much has been found to justify that date).

For us, talk of these “original” Olympics conjures up a picture of plucky amateur athletes – men only, of course – fiercely patriotic, nobly competing in a very limited range of sports: running races, chariot races, wrestling and boxing, discus and javelin throwing. There were no team games then, let alone such oddities as synchronized swimming. Everything was done individually, for the pure glory of winning – and no material reward. You didn’t even get a medal if you came first in an Olympic competition, just a wreath of olive leaves and, if you were lucky, a statue of yourself near the stadium, or in your home town. The luckiest might also be celebrated in one of the Victory Odes, specially composed by the poet Pindar, or one of his followers, which are still read 2,500 years later.

What is more, the whole contest was performed in honor of the gods. Olympia was a religious sanctuary as much as it was a sports ground, and the Games united the Greek world under a single religious cultural banner. Although the warring city-states of Greece were usually doing just that – warring – every four years the Olympic truce was declared to suspend conflict for the period around the competition, to allow anyone from everywhere in the Greek world to come and take part. It was a moment when sport and fair play trumped self-interested military conflicts and disputes.

As with most stereotypes, there are grains of truth here: there were no medals and no women at the ancient Olympics, for example. But taken altogether, as a picture of what the Games were really like back then, this tissue of cliches is deeply misleading. It owes more to the preoccupations of the founders of the modern Olympic movement than it does to the ancient Greeks themselves. Men such as Baron Pierre de Coubertin, who successfully relaunched the modern Olympics in 1896, systematically projected their own obsessions – from their disapproval of alcohol to their rather woolly ideas of world peace and harmony – on to the early centuries of the ancient Games and their participants.

“It’s easy to ignore the fact that the ancient Games were “Roman” for almost as long as they were “Greek” – in the sense that they were celebrated under Roman rule and sponsorship from the middle of the 2nd century BC until they were abolished by Christian emperors at the end of the 4th century AD.”

Panathenaic amphora, a victory prize from ca. 530 BC depicting a foot race, attributed to the painter Euphiletos. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

© Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece/Kapon Editions Courtesy

One particular obsession of those in charge of the modern Olympics, until as late as the 1980s, has been the cult of the amateur. Coubertin and his successors sometimes cruelly policed the frontier between the amateur contestants – who were warmly welcomed as modern Olympians – and the professional interlopers, who were definitely not. One of the most mean-spirited incidents in modern Olympic history is the story of the brilliant American athlete Jim Thorpe, who won both the pentathlon and the decathlon at the Stockholm Games of 1912. He was an ordinary working man, part native-American, and a famously down-to-earth character: on being presented with a commemorative bust of himself by King Gustav of Sweden, he is supposed to have replied “Thanks, king.” It later came to light that he had received some trivial payments ($25 a week) for playing minor league baseball in the US; he was reclassified as a professional, stripped of his medals and asked to return the bust. A change of heart did not come until 1983, when his family was sent some replica medals. Thorpe had died in 1953, in utter poverty.

For Coubertin and his like, the Classical Olympic Games were the precedent for this rule. They would have insisted that the great competitors of the 5th century BC were noble amateurs, not vulgar money-grubbers selling their athletic prowess for cash. Well, yes and no. The competitors at the Classical Olympics were certainly not “professionals” in our sense. But that is largely because the familiar divide between “amateurs” and “professionals” did not operate in Classical Greece. To put it another way, if we approach the ancient Games armed with modern categories of sporting competition, we do not find many “grubby professionals,” but we don’t find much “noble amateurism” either.

For a start, the winning athletes may not have received cash prizes at Olympia, but many did very nicely when they got back home: not just honorific statues, but free meals for life at the state’s expense, cash handouts and tax exemptions. And there are hints of something closer to a professional athletics circuit than the founding fathers of the modern Games would have liked. According to the ancient lists of Olympic victors, between 588 and 488 BC, 11 winners in the short sprint race – about a third of the total number – came from the not particularly large Greek town of Croton, in southern Italy. Maybe the people of Croton just got lucky, or maybe they lived in some fanatical athletics boot-camp. More likely they were buying in top talent from other cities, who wore the colors of Croton.

But no less damaging to the idea of the ancient world’s pure amateurism is the fact that some of the most prestigious wreaths of victory went not to the athletes themselves, but to men whom we would call “sponsors.” The grandest event of the Games was the chariot race, but the official winner was not the man who actually did the dangerous work, standing in the chariot and controlling the horses, but the king, princeling or plutocrat who had funded him and paid for the training, at no doubt vast expense. In fact, this was the only Olympic event at which a woman could claim victory – as one Spartan princess did in the 4th century BC. As far as we know, she did not get a victory ode (though she did get a statue at Olympia). But some of Pindar’s best-known Olympian poems were written to celebrate not athletes at all, but these grandees who had shown no sporting prowess whatsoever, just a deep pocket.

The other main myth about the ancient Olympics that Coubertin and his colleagues promoted was their contribution to peace and understanding. This centered on the so-called Olympic Truce, which has increasingly been turned into the model for our own romantic ideal of a gathering of all nations, friend or foe, under the Olympic banner. But in fact, the ancient Games were by no means consistently marked by an atmosphere of national or international harmony.

There are, it is true, some ancient references to a cessation of hostilities to ensure that competitors and their trainers could reach the Games safely, and in one of the temples at Olympia you could still see, in the 2nd century AD, a supposedly very early document – almost certainly a later forgery – that referred to the origins of this “truce.” But how it was enforced, and by whom, is anyone’s guess.

Sometimes it wasn’t enforced. On one occasion, in the 4th century BC, there was actually a full-scale battle in Olympia itself during the Games. A force from the nearby town of Elis (which traditionally ran the Olympics) invaded the site, right in the middle of the pentathlon, to get control back from the rival town of Pisa, which had temporarily taken over. And the truce certainly didn’t prevent people exploiting the Games for violent power struggles back in their own cities. In the 630s BC, there was a coup in Athens against one of the leading families while they were away competing in the Olympics.

In general, the real-life experience of competing in the ancient Olympics was a far cry from what Coubertin imagined. The modern Olympics are (officially at least) committed to the ideal of fair play. However much rivalry there is about the medal table, participation is still supposed to be more important than winning. That is nothing like the ancient Games, where winning was everything and there was no such thing as honorable losers. Contestants fought viciously, and cheated. When one Athenian contestant in the 4th century BC was caught red-handed attempting to bribe his rivals in the pentathlon, a fine was imposed. The Athenian authorities thought this so unreasonable that they threatened to boycott the Games in future – though they gave in when the Delphic oracle refused to give them any more oracles unless they coughed up the money.

The ancient Games were a decidedly uncomfortable one for the spectators too. The occasion attracted crowds of visitors, but there were hardly any decent facilities for them: it was blisteringly hot, with little shade; there was no accommodation for the ordinary visitor (beyond a no doubt squalid and overcrowded campsite); and the sanitation must have been rudimentary, at best, given the inadequate water supply to the site, which could not even guarantee enough clean drinking water to go round.

“Some of Pindar’s best-known victory odes were written to celebrate not athletes at all, but grandees who had shown no sporting prowess whatsoever, just a deep pocket.”

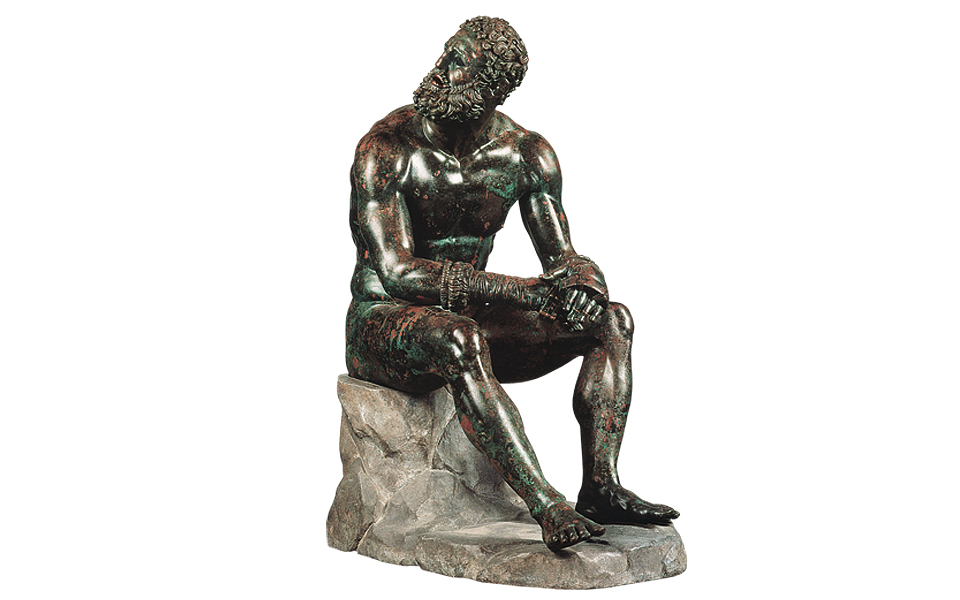

Boxer at Rest, a splendid bronze statue depicting a boxer resting after a bout. Inlaid copper represents drops of blood fallen from his face onto his arm; his body also displays signs of injury. Dated between the late 4th and mid-1st centuries BC. (National Roman Museum)

But this is where the Romans come in. The likes of Coubertin lamented the Roman influence on the Games, with the growth of a professional class of competitor, and the malign influence of the Roman emperors (who occasionally took part in events and were supposed to have had the competition rigged so that they could win). For the spectators, though, it was the sponsorship of the Roman period that made the Olympic Games a much more comfortable and congenial attraction. The Romans may not have solved the traffic congestion, but they installed vastly improved bathing facilities, and the Roman senator Herodes Atticus laid on, for the first time, a reasonable supply of drinking water, building a conduit from the nearby hills and a fountain in the middle of the site. Predictably, perhaps, some curmudgeons thought this was spoiling the Olympic spirit. In a typically ancient misogynist vein, Peregrinus accused Herodes of turning the visitors into women, when it would be better for them to face thirst like men. For most visitors, though, an efficient fountain must have been a blessed relief.

In some ways the character of the Games continued under the Romans with little change, and sporting records were broken. In AD 69, for example, a man called Polites from modern Turkey won two sprint races and the long distance – a considerable achievement given the different musculature required. Apparently it was the first time it had been done in almost a millennium of Olympic competitions. And there was the same disdain for losers. One poem of the Roman period pillories a hopeless contestant in the race in which everyone ran dressed in armor. He was so slow that he was still going when night fell, and got locked in the stadium overnight – the joke was that a caretaker had mistaken him for a statue.

But in other respects the Romans worked towards an Olympics that is much more like our own than the earlier “true Greek” version. Whatever his other faults, Nero introduced some “cultural” contests into the Games. The Olympics had always been (unlike other Greek athletic festivals) resolutely brawny, with no music or poetry competitions. Nero didn’t succeed in injecting much culture for very long (it soon reverted to just athletics), but, knowingly or not, the 19th-century inventors of the modern Olympics took over his cultural aims. It’s easy to forget that in the first half of the 20th century, Olympic medals were offered for town planning, painting, sculpture and so on. Coubertin himself won the 1912 gold medal for poetry with his Ode to Sport. It was truly dreadful: “Sport thou art Boldness! / Sport thou art Honor! / Sport thou art Fertility!” …

The most lasting contribution of the Romans, though, was to make the Olympics, as we now think of them, truly international. The Classical Greek Olympics had been rigidly restricted to Greeks only; Roman power opened up the competition to most of the then known world. It is a nice symbol of this that the last-named victor at Olympia in 385 AD, the prizewinner in the boxing contest, was a Persian from Armenia called Varazdates.

Ironically, though, it was during the Roman period that the nostalgia about the early Games started. At the same time as the Romans were ploughing money into the Olympics and making them an international celebration, authors were already inventing the romantic image of the great old Greek days of Olympic competition. Writing in the 2nd century AD, Pausanias devoted two volumes of his guide to the noteworthy sites of Greece to the monuments of Olympia. He sees the place almost entirely through Classical Greek spectacles. He is the source of most of our stories about the notable Olympic achievements and heroes of centuries earlier. He doesn’t even mention Herodes Atticus’ splendid Roman fountain, which he must have seen as he walked round the sanctuary. Even Peregrinus, speechifying as he was about to throw himself on the pyre, compared himself to the great tragic heroes of “Classical Greece,” centuries earlier. The Games have been a nostalgic show for longer than we can imagine. It has probably always seemed that they were better in the past.

“One poem of the Roman period pillories a hopeless contestant in the race in which everyone ran dressed in armor. He was so slow that he was still going when night fell, and got locked in the stadium overnight.”

A major restoration project is bringing...

In Syntagma Square, marble, flame, and...

A forgotten world comes to life...

The Olympic elite, Hollywood’s finest, the...