In July this year, archaeologists from the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology reported the discovery of an ancient shipwreck at the site of Thônis-Heracleion – once Egypt’s largest and most prosperous seaport.

Initial inspection of the ship’s remains, lying in less than 5 meters of water, has revealed it to be rare type of warship – a “fast galley” (similar to a hemiolia or trihemiolia?), dating to the 2nd century BC.

The find is hugely significant because ancient warships were lightly ballasted and seldom sank when destroyed in battle, instead being towed away or ran aground by the surviving crew. As such, precious few remains of these vessels have been found to help archaeologists understand their construction and design.

Egypt’s “Atlantis”

Lying submerged in the gulf of Abu Qir (Aboukir) Bay, 2.5 km from the present-day coastline, the ancient port city of Thônis, its original Egyptian name, was founded sometime in the 8th century BC. Developed as a network of canals near the Canopic mouth the Nile, the port served as a vital gateway for foreign traders, becoming Egypt’s main seaport on the Mediterranean Sea during the Late Period (664-332 BC)

Over time, the city faced stiff commercial opposition from nearby Alexandria, founded by Alexander the Great in 331 BC. Under Ptolemy I, one of Alexander’s “Successors,” Alexandria soon became the largest and busiest port in the Mediterranean, the seat of the Greek-Macedonian Ptolemaic Dynasty (305-30 BC), home of the famous Pharos lighthouse, and one of the most important cultural centers in the Hellenistic world.

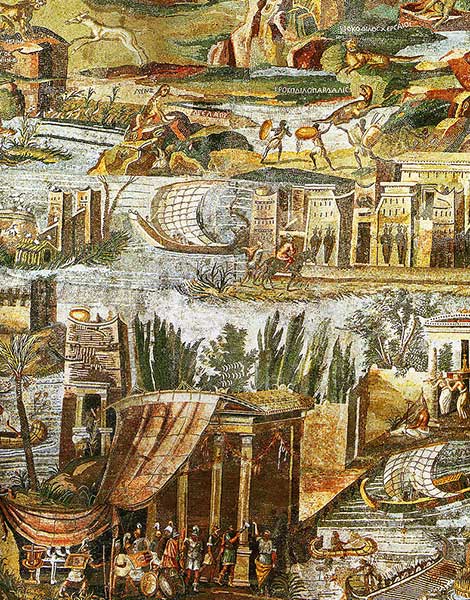

© Stella

Thônis-Heracleion gradually disappeared into the sea between the 1st century BC and the 8th century AD, destroyed by earthquakes and then flooded due to land subsidence and rising sea levels. The city was long forgotten, near-legendary even, until 1933, when a Royal Air Force pilot flying over Abu Qir Bay spotted ruins under the water.

Decades later, in 2000, the site was rediscovered by French archaeologist, Franck Goddio, founder of the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology.

Since then, Goddio and his team, in collaboration with the Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology at the University of Oxford and the Egyptian authorities, have embarked on an ambitious program of survey and excavation, making startling discoveries season after season.

© Matt Boulton

Hellenistic fast galleys

The remains of ancient temples and the recovery of colossal statues, stelae, precious jewellery and hoards of coins have revealed a once prosperous city. More than 700 ancient anchors and the remains of dozens of shipwrecks dating from the 6th to the 2nd century BC have also highlighted the intense maritime activity that went on before its demise.

Among the latest round of discoveries, including the well-preserved remains of a Greek funerary complex dating back to the first years of the 4th century BC, is the wreck of a rare type of vessel, the likes of which are virtually unknown in the archaeological record. Located with a sub-bottom profiler, a powerful remote sensing tool used to detect anomalies under the seabed, the archaeologists pinpointed the fragmentary remains of a narrow, shallow hull, its wood preserved for over 2,200 years under layers of stone rubble and muddy clay.

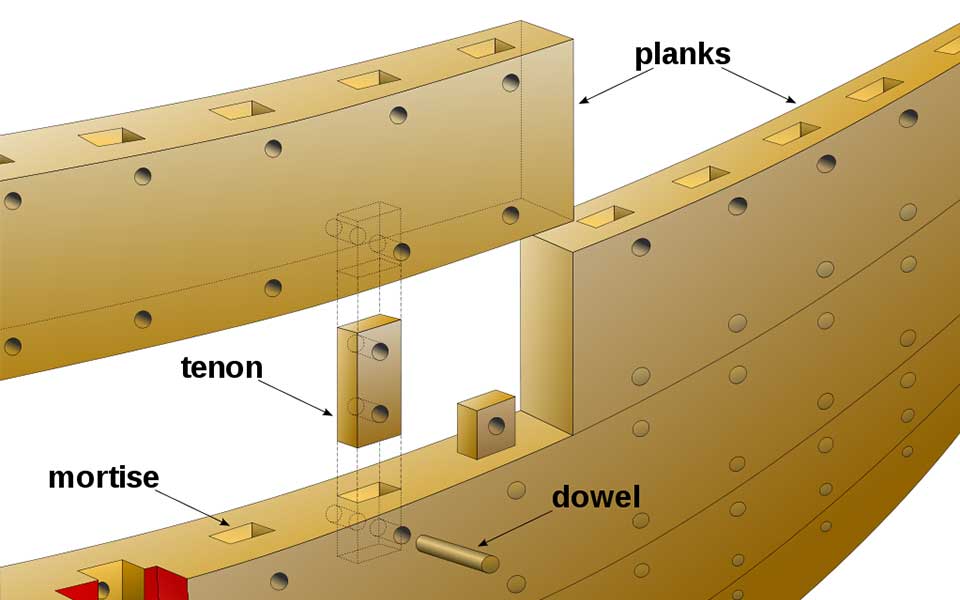

According to the team, the hull mixes construction methods used by both Egyptian and Greek shipbuilders – including locked mortise-and-tenon joints, a technique inherited and adapted by Greek shipwrights from a much earlier method developed by the Phoenicians. This method of joinery, which involved securing planks together using a pegged socket, enabled the hull to remain watertight.

© Eric Gaba

Based on the dimensions of the existing hull, the vessel would have been around 25 meters in length, with a length to breadth ratio of 6-to-1 – strikingly similar to modern-day warships. Built for speed, the team believe it may have served as a type of “fast galley,” propelled by a crew of skilled oarsmen. Its flat bottom and shallow draft suggests it was built for operations in the littorals of the Nile and its delta, occasionally deploying a sail in fair winds.

According to the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology, the craft was likely “hit by huge blocks from the famed temple of Amun, which was totally destroyed in a cataclysmic event in the 2nd century BC.”

Fast galleys in the Hellenistic era, the period that coincides with the Ptolemaic kingdom in Egypt, were ubiquitous among pirates, descended from the earlier triacontors (“30 oars”) and pentecontors (“50 oars”) of the 6th and 5th centuries BC. The state-run navies of the time tended to favor much bigger, heavier warships with multiple banks of rowers known as polyremes, but smaller, more manoeuvrable vessels also took their place in the line of battle.

These fast galleys, known as hemiolia and trehemiolia, were often deployed as scout ships or “raiders,” used to harass and attack maritime supply lines during military campaigns. Their small size and shallow draught also enabled them to be used in rivers and inland waterways, most famously by Alexander the Great in the Indus and Hydaspes.

Trehemiolia in particular were a hugely successful design, used in anti-piracy operations by the Rhodian navy from the late 4th century BC.

© Marsyas

Capable of reaching speeds comparable to the much larger three-banked trireme, the principle ship of the line in the preceding Classical period, Trehemoilia were soon adopted by Hellenistic navies in the eastern Mediterranean, including the Ptolemaic.

Ptolemaic Sea Empire

Following the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, his successors (the “Diadochi”) fought for control over his vast empire. Ptolemy, one of Alexander’s closest companions, established his dynasty in Egypt, which lasted from 305 to the death of his descendent Cleopatra VII in 30 BC.

In the struggle for supremacy, the armies of the Diadochi, among them Seleucus and Antigonus, clashed in a decades-long series of wars. The construction of ever bigger and more complex warships, built to project military power and prestige in the eastern Mediterranean, signaled an early arms race.

Ptolemy was quick to establish a well-equipped, well-trained naval force by the end of the 4th century BC, deploying fleets across the eastern Mediterranean and expanding territorial control over neighboring Cyrenaica (modern-day Libya) and strategically important Cyprus.

The newly-discovered shipwreck at Thônis-Heracleion, dated to the 2nd century BC, may well have served as a fast galley in the later Ptolemaic navy, at a time when the use of larger vessels had given way to much smaller, lighter warships – ultimately cheaper and easier to maintain.