Sacred Summits: Greece’s Ancient Mountain Sanctuaries

From Crete to Olympus, hike the...

The Acropolis, as imagined in an 1846 painting by German architect and artist Leo von Klenze (1784-1864).

© Leo von Klenze - Neue Pinakothek, Munich / Public domain

Imagine walking through the bustling streets of ancient Athens, the sun high in the sky, casting its golden light on the majestic marble temples and monuments of the Acropolis. The air is filled with the hum of conversation, the scent of freshly baked bread, and the occasional laughter of children playing in the Agora. This was summer in ancient Athens, a time of vibrant activity, religious fervor, and communal gatherings.

As the mercury rises and we try to stay cool in the scorching mid-July temperatures in Greece, let’s journey back in time to explore what life was like in the ancient city of Athens during the summer months, how people dressed and coped with the heat, and the festivals that brought the city to life.

The Ancient Agora of Athens, the beating heart of the city. In the background can be seen the well-preserved Temple of Hephaestus.

© Shutterstock

As with virtually all pre-industrialized societies, the daily arc of the sun dictated the rhythms and patterns of everyday life in ancient Athens. In the summer season (“Θέρος” in ancient Greek), which ran from July to early October, the city’s inhabitants would rise long before dawn to take advantage of the cooler morning hours. In the early morning light, the Agora, the beating heart of public life, would be abuzz with merchants selling their wares, philosophers engaging in debates, and citizens discussing the latest round of politics. The hustle and bustle would peak in the mid- to late-morning before the intense afternoon heat set in.

During the hottest part of the day, many Athenians would retreat indoors for a midday rest, a practice not unlike the modern “siesta.” Without the luxury of air conditioning or ceiling fans, they had to be creative in coping with the heat. Thanks to well-preserved archaeological remains, we know that the design of their homes played a crucial role in keeping cool during the scorching summer months.

The Makrigianni site, located underneath the Acropolis Museum, was a bustling neighborhood of the Classical city. During excavations, archaeologists unearthed a honeycomb of streets, alleyways, houses, public baths, and workshops.

© Panagiotis Tzamaros/Intime News

Athenian houses were typically built with thick walls made of mudbrick or locally quarried stone, materials known for their insulating properties. These thick walls helped to maintain a cooler indoor temperature by absorbing and slowly releasing the heat. The houses were often oriented to take advantage of prevailing winds, with doorways and openings positioned to facilitate airflow and provide natural ventilation.

To help keep the interiors cool, the windows in these homes were small and positioned high on the walls, minimizing the direct entry of sunlight while allowing for air circulation. Wooden shutters or lattice screens were used to control the amount of sunlight entering the rooms, creating a dim and cool interior.

Another central feature of Athenian domestic spaces was the courtyard, an open space typically surrounded by the main rooms of the house. Courtyards served multiple purposes, including providing light and ventilation to the interior spaces, and acting as a social and functional hub for the household.

Courtyards often featured shaded areas created by pergolas covered with climbing plants like ivy, or by awnings made of linen or finely spun wool. These shaded spots offered a cool retreat from the intense midday sun. In wealthier households, courtyards might include a small garden with trees and plants, which helped to create a more pleasant microclimate by providing shade and releasing moisture into the air through transpiration.

In some Athenian homes, particularly those of the more affluent citizens, courtyards might also include small water features such as fountains or basins. The presence of water not only provided a cooling effect through evaporation but also added an aesthetic and tranquil element to the home environment.

Women drawing water at the fountain house. Attic black-figure hydria (water jug), c. 530 BC. On display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

© Marie-Lan Nguyen (2011) / Public domain

Clothing also played a significant role in staying cool in the long summer months. Ancient Greeks tended to wear light, loose-fitting garments made of linen, thin wool, or, in the case of the super wealthy, silk; materials that allowed the skin to breathe and provided comfort in the heat.

Men typically donned a chiton, a type of tunic made of light linen that could be draped in various ways to adjust for comfort and airflow. Women wore a long flowing garment called a peplos, pinned at the shoulders. A himation, or cloak, could be draped over the head and shoulders for additional shade. The design of these garments was not only practical but also allowed for a degree of personal expression and style.

Sandals were the footwear of choice, allowing for ventilation and comfort. Made from leather, usually ox-hide, these sandals were simple in design but effective in keeping feet cool and protected from the hot cobbled streets. It was also common for rustics, slaves, and even some philosophers (e.g., Socrates, c. 470-399 BC), to go barefoot.

A broad-brimmed hat with an attached cord called a “petasos,” useful for keeping the sun off the face and back of the neck, was also worn in the summer.

For more information on ancient Greek clothing, click here.

"Sappho and Alcaeus," completed in 1881 by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912).

© Google Art Project / Public domain

Despite the challenges of the summer heat, Athenians maintained a vibrant social and community life. The Agora remained a focal point of daily interactions, with shaded colonnades providing some relief from the sun. Public fountains and communal wells were also important gathering spots where people could access fresh water and cool down.

In the evenings, as the temperature dropped, the city would come alive again with social gatherings, public events, and family activities, much like life in modern day Athens. The cooler hours provided an opportunity for Athenians to enjoy outdoor spaces, engage in communal dining, and participate in cultural and religious activities.

Greek vase depicting runners at the Panathenaic Games, c. 530 BC

© MatthiasKabel / Public domain

Summer in ancient Athens was a time of significant religious and civic activities, with festivals that brought the community together in celebration, worship, and competition. These events were not only a means of honoring the gods but also an opportunity for social bonding and reinforcing community ties.

The biggest summer event in Athens was one of the grandest in the entire ancient Greek world: the Panathenaia (literally, “the all-Athenian festival”), held every four years in honor of the goddess Athena, the patron deity of the city. Drawing participants and spectators from all over Greece, the festival featured a range of athletic and equestrian competitions, reminiscent of the Olympic Games. These included foot races, wrestling, boxing, “pankration” (an ancient form of mixed martial arts), and chariot racing. Music and artistic competitions were also a key part of the proceedings. Musicians competed in playing the lyre and the “aulos” (a double-reeded instrument), while poets recited epic poems such as those of Homer and Hesiod.

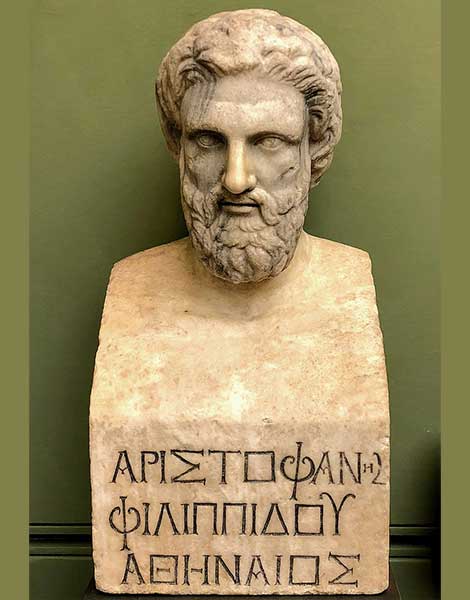

The highlight of the festival was the grand procession, known as the Panathenaic Procession. We know a great deal about this event thanks to the detailed descriptions left by contemporary authors, including the playwright Aristophanes (c. 446-386 BC) and the historian Herodotus (c. 484-425 BC), as well as the beautiful decorative sculptures that once adorned the 160m-long frieze of the Parthenon temple. Held on the 28th of Hekatombaiōn (mid-summer), the procession began at the Dipylon Gate, the main gate of the old city walls, located in the suburb of Kerameikos, and wound its way through the city, culminating at the Acropolis. Participants included Athenian citizens, metics (resident foreigners), and representatives from allied states, each carrying offerings, which included the new robe (peplos) woven by the Ergastinai (young women of noble families) for the statue of Athena, symbolizing the city’s devotion to its patron goddess.

This preserved section of pavement, near the Agora’s Acropolis entrance, marks the path of the Panathenaic Way.

© Shutterstock

Another important festival was the Boedromia, held on the 7th of Boedromion (late summer) in honor of Apollo Boedromios, the “helper in distress.” This festival celebrated Athens’ military victories attributed to Apollo’s divine intervention and support during wartime. According to ancient sources, the Boedromia commemorated key events in the Epic Cycle of Greek mythology, like Apollo aiding Theseus, the legendary hero and founder of Athens, against the warlike tribe of women warriors, the Amazons. Mythological narratives like these underscored the festival’s significance in reinforcing communal identity and gratitude for divine protection.

Rituals during the Boedromia included sacrifices to Apollo and his twin sister, Artemis, reflecting the festival’s dual focus on divine aid and martial prowess. Offerings of animals, such as goats or sheep, were central to these rites. The festival was not merely a religious observance but a civic event that brought the community together, emphasizing the interconnectedness of religion, warfare, and civic duty.

Like the Panathenaia, the Boedromia highlighted the Athenians’ belief in the gods’ active role in their history, reinforcing the notion that divine favor was crucial to the city’s success and survival. It provided a moment for Athenians to collectively honor their gods and celebrate their shared heritage and resilience.

Bust of Aristophanes, 1st century AD. On display in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

© Alexander Mayatsky / Public domain

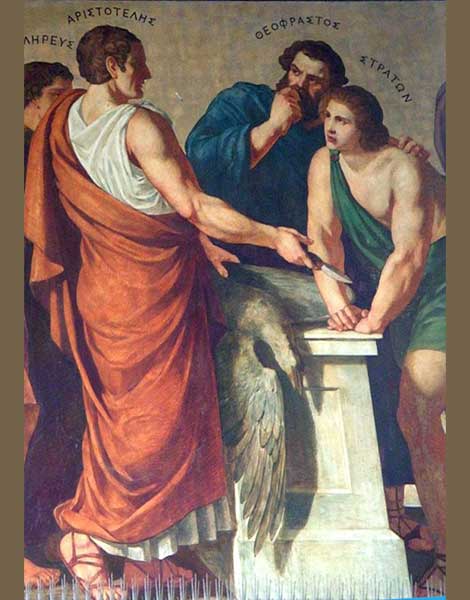

Aristotle, Theophrastus, and Strato of Lampsacus. Part of a fresco in the portico of the University of Athens, painted by Carl Rahl, c. 1888.

© National and Kapodistrian University of Athens / Public domain

The heat of the Athenian summer did not go unnoticed by ancient writers, who often captured the season’s challenges and the ingenious methods that people employed to stay cool.

In his comedic play “The Clouds,” Aristophanes humorously depicts the oppressive summer heat. The play, known for its satirical take on Athenian society and intellectual trends, includes scenes that illustrate the lengths to which people would go to find relief. For example, he describes characters seeking shade under trees, using fans made of leaves, and even jumping into fountains to cool off. One famous quote from the opening lines of the play has the character Strepsiades lamenting the long, sleepless nights, exclaiming, “Oh, what a terrible thing is the heat! Even the lizards, I think, must be finding it hard to bear.”

Xenophon (c. 431-354 BC), in his “Memorabilia,” provides a more practical account of dealing with the summer heat. As a student of Socrates, Xenophon often focused on the practical aspects of daily life and personal conduct. In his writings, he discusses the importance of finding shade and staying hydrated, two essential strategies for coping with the intense heat. In one passage, Xenophon recounts a conversation where Socrates advises a friend to “seek the shelter of the stoas and drink frequently from the fountains to ward off the ill effects of the sun.”

Theophrastus (c. 371-287 BC), a student of Aristotle, offers another perspective in his work “Characters.” In this collection of character sketches, he describes various types of people and their behaviors. One such sketch, “The Man of Petty Ambition,” humorously details how some Athenians would take advantage of the heat to show off their wealth and status. These individuals would stroll through the Agora with parasols and attendants fanning them, turning the necessity of staying cool into a display of social prestige.

Built in the 2nd century AD, the Odeon of Herodes Atticus is one of the main performance venues of the annual Athens & Epidaurus Festival.

© Shutterstock

Modern Athenians face similar challenges with the summer heat, though rising temperatures and the current climate crisis have exacerbated the situation. Today, air conditioning and other mod-cons provide much-needed relief, but the ancient strategies of seeking shade and wearing light clothing remain relevant. The city’s landscape has certainly changed over the past 2,500 years, resembling a giant concrete labyrinth with far fewer green spaces, making the urban heat island effect a pressing issue, but contemporary festivals, like the Athens Epidaurus Festival, continue to bring people together, echoing the communal spirit of ancient times.

Indeed, life in ancient Athens during the summer was a blend of adaptation to the environment, communal activities, and religious devotion. The ingenuity of the Athenians in coping with the heat, their vibrant festivals, and the daily hustle and bustle paint a picture of a society deeply connected to its natural and social environment.

As we head deeper into the Anthropocene, navigating our own hot summers, reflecting on the experiences of ancient Athenians can offer insights into sustainable living and the enduring importance of community. So next time you find yourself seeking shade or enjoying a summer festival, remember the Athenians who walked these paths before us, embracing the sun and the vibrant life it brought to their city.

From Crete to Olympus, hike the...

Lost to earthquakes, swallowed by the...

From temples and festivals to front...

Discover festivals, beaches, food, and hidden...