8 Hidden Greek Museums Just Steps from the...

From olive presses and traditional costumes...

The Parthenon, chief temple of the goddess Athena, is the visual centerpiece of the Athenian Acropolis.

© Shutterstock

Of all the world’s heritage sites, the Acropolis of Athens is the ultimate adaptation of monumental architecture to a natural landscape. Made of white marble from nearby Mount Penteli, the iconic ensemble of buildings on the Sacred Rock still visible today include the Parthenon, the Propylaea, the temple of Athena Nike, and the Erechtheion. Together, they create a monumental landscape of unique beauty, a powerful reminder of the artistic and intellectual achievements of the ancient Greeks, and serve as an enduring symbol of Western culture and democracy.

Erected in the second half of the 5th century BC during the ambitious building program of the great statesman Pericles (c. 495–429 BC), the monuments of the Athenian Acropolis formed part of a religious sanctuary to honour the Olympian goddess of wisdom, Athena, chief patron and protector of the city. Reflecting the character and poise of the goddess they once venerated, the monuments themselves are a model of proportion and harmony; architectural masterpieces that capture the spirit of Athens during the Golden Age of Pericles.

The Athenian Acropolis, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is an icon of ancient Greek culture and an enduring symbol of democracy.

© Shutterstock

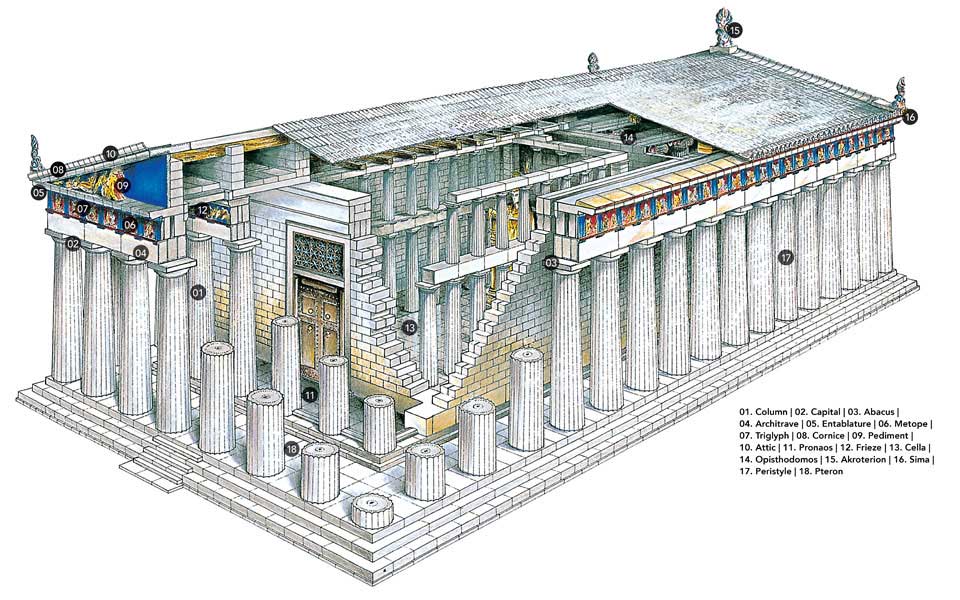

The most outstanding monument is the Parthenon, “temple of the virgin goddess,” widely regarded as the finest example of Classical Greek architecture. A colossal temple of the Doric order, the Parthenon was the visual centerpiece of the Athenian Acropolis, designed and built by the architects Iktinos and Callicrates between the years 447 and 338 BC.

In its original state, the temple comprised over 70,000 architectural members, each one handcrafted to precision.

A recreation in modern materials of the lost colossal statue by Pheidias, Athena Parthenos by Alan LeQuire (1990) is housed in a full-scale replica of the Parthenon in Nashville’s Centennial Park. She is the largest indoor sculpture in the western world.

© Dean Dixon

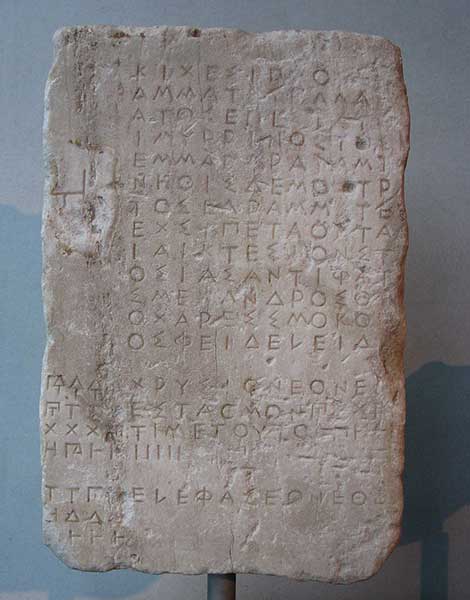

Ancient Greek inscription containing account of the supervisors for the construction of the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue, 440/439 BC. New Acropolis Museum, Athens

© Tilemahos Efthimiadis

The Parthenon housed a now lost cult statue of the goddess, Athena Parthenos (the “Virgin”), made by the master sculptor Pheidias and his assistants. Described by ancient writers, the 11.5-meter-tall statue made of gold and ivory portrayed the goddess as a triumphant warrior, holding the figure of winged victory Nike in the palm of her outstretched right hand – a celebration of the Greek victory over the invading Persians, and Athenian democracy as, in the words of Pericles, the “highest form of constitution” [from Pericles’ Funeral Speech, Thucydides].

One of the largest temples ever built, the Parthenon had 46 outer columns and 23 inner columns – 8 columns at either end (octastyle) and 17 on the long sides. The dimensions of the temple’s base (stylobate) are 69.5 meters by 30.9 meters, while the exterior columns are 10.4 meters high. The roof consisted of large overlapping marble tiles knowns as imbrices and tegulae, supported by massive wooden beams.

The temple embodies a number of pioneering architectural features and refinements, including a series of ingenious optical illusions that trick the viewer into thinking they’re looking at a giant construction made up straight lines and perfect right angles. In fact, there are virtually no straight lines in the Parthenon. Instead, the architects incorporated numerous hidden devices, including tapered walls, swollen and slightly inward leaning columns, and a domed stylobate to avoid optical “sagging” in the middle of the building.

Even in antiquity, these subtle refinements were legendary.

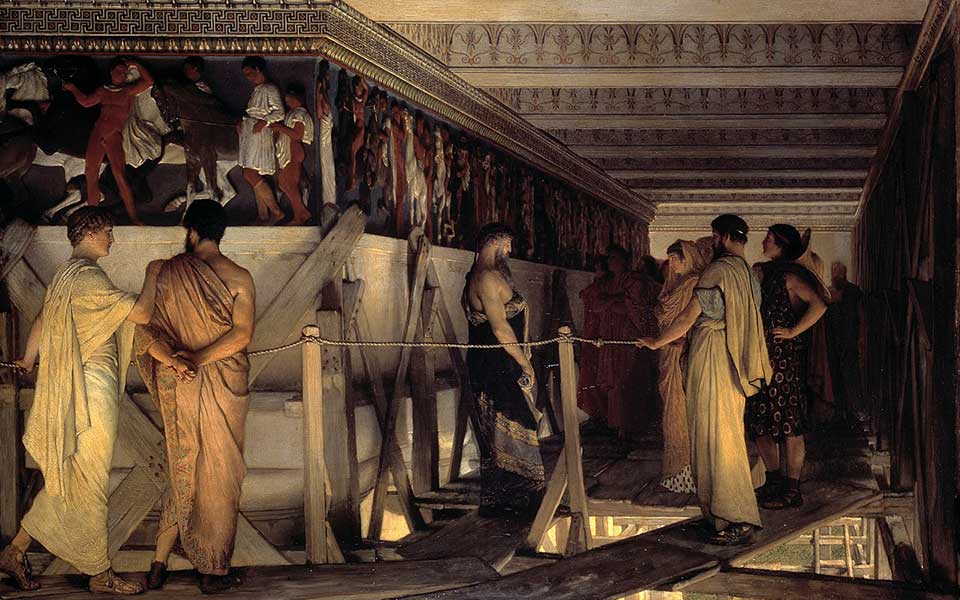

Pheidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends, painting by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1868)

© Birmingham Museums

An essential part of any Greek temple was its adorning art. Master sculptors created a feast for the senses by contrasting brightly colored sculptures and reliefs across the upper part of the temple with the austere simplicity of the pillared colonnade below. As such, the decorative sculptures were not freestanding works of art but integral architectural members of the temple’s design.

Temple art served an important religious purpose, depicting the Olympian gods and popular scenes from Greek mythology. Scholars have argued it may have also served a pedagogical function, educating onlookers about the origin stories of their city and patron gods.

What is known is that Greek city states raised enormous amounts of revenue to build bigger and more elaborate temples, not only to glorify the gods but as a conspicuous display of their own power and wealth. In the case of the Parthenon, never before had a Greek temple been so richly designed and decorated.

Although construction of the Parthenon was completed in 438 BC, work on its lavish sculptural decoration, consisting of the large triangular pediments, metopes, and the 160-meter-long frieze, continued until 432 BC. Under the watchful eye of master sculptor Pheidias, a team of highly skilled artists rendered the Pentelic marble into a visual narrative that not only commemorated the mythological foundations of Athens, now the most powerful city-state in the Greek world, but celebrated the decisive role of democracy – “rule of the people” – in the victory over the Persians.

Proposed reconstruction of the east pediment in the Acropolis Museum, Athens.

© Tilemahos Efthimiadis

For the large triangular pediments on the east and west façades, Pheidias and his sculptors rendered 50 over-life-sized figures fully in the round; an incredible feat considering the backs of the sculptures would never have been seen once they were in position.

Above the main entrance, the east pediment depicted the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus, attended by the other gods. The statues of Zeus and Athena, standing three meters tall, took pride of place in the center, the newly-born goddess already fully armed and ready for war.

The west pediment depicted her famous contest with the sea god Poseidon for the patronship of the city, the former having offered the Athenians a salty spring, the triumphant goddess the first olive tree. What was striking about the Parthenon’s decorative sculptures was that Athena, the patron deity, appeared on both pediments.

Detail of the west metopes, still attached to the Parthenon.

Reconstruction of the colors on the entablature of the Parthenon. "Kunsthistorische Bilderbogen," Verlag E. A. Seemann, Leipzig. 1883.

Below were the metopes, each one measuring around 1.25 x 1.2 meters. Carved in high relief, they ran around the four sides of the peristyle, just above the columns: 32 on the long sides of the building facing north and south, and 14 on each of the façades.

Over the entrance on the east façade, the Olympian gods battled the Giants, offspring of Gaia (Earth) and Uranus (Sky), for control of the Universe. This popular theme in Greek mythology, known as the “Gigantomachy,” was symbolic of the struggle of order over chaos, the new gods over the old.

Centauromachy - a Centaur and Lapith, locked in deadly combat. South metope, on display in the British Museum.

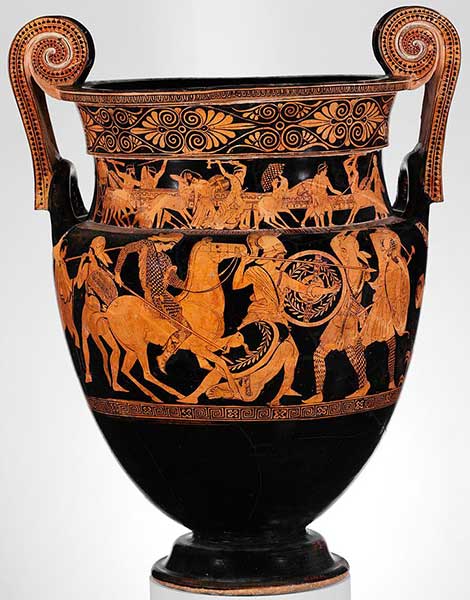

Volute krater attributed to the Painter of the Woolly Satyrs, depicting the Amazonomachy and, on the collar, the battle of the Centaurs and Lapiths.

© Metropolitan Museum of Art

On the west façade, Greek soldiers in full hoplite armor were shown fighting the Amazons (“Amazonomachy”), a fierce tribe of warrior women from the east, a clear metaphor for the Persians. Each metope depicted a tautly composed one-on-one duel.

For the long side of the temple facing south, Pheidias chose the theme of the “Centauromachy,” the epic story of the battle between the civilised Lapiths (Greeks) and the half-man, half-horse Centaurs (typifying barbarians) at the wedding of Perithous, king of the Lapiths, a mythological kingdom in Thessaly. Represented in one of the metopes is Theseus, a guest at the wedding and the legendary first king of Athens.

The north-facing metopes depicted scenes from the fall of Troy, another metaphor for the Persian Wars.

The so-called Peplos scene. Block V from the east frieze of the Parthenon, c. 447–433 BC, on display in the British Museum.

The subject of the frieze was by far and away the most characteristic feature of the Parthenon’s decorative art; Phiedias’ most daring and ingenious choice. Departing from the popular themes and stories from Greek mythology, the master sculptor created a stunning visual narrative of the Athenians themselves in the sacred act of worship.

Measuring 160 meters in length and around one meter high, the frieze ran around all fours sides of the temple between the outer colonnade and the inner cella (naos). Carved in low relief and overlapping across 115 slabs of Pentelic marble, it depicted the Panathenaic Procession, a religious ceremony that took place every year, and with greater splendour every four years (the Greater Panathenaia), to celebrate the birth of the city’s patron goddess Athena.

The procession followed the Sacred Way through the city, past the Agora and up the Acropolis to bring a new robe (peplos) to the ancient olive-wood cult statue of the goddess housed in the Erectheion, the smaller temple next to the Parthenon.

Cavalcade. Block II from the west frieze of the Parthenon, c. 447–433 BC, on display at the British Museum.

© Jastrow

On the west frieze, figures were shown gathering for the procession: maidens carrying jars of water, wine and olive oil, young boys carrying trays of cakes, herdsmen mustering the rams and oxen for sacrifice, all jostling alongside weavers, musicians, and city dignitaries. The procession then spilled over the long sides of the temple, depicting athletes, marshals, charioteers and their passengers wearing full hoplite armor, and elders holding olive branches.

Around seventy percent of the frieze was filled by the cavalcade, ranks of young cavalrymen representing the ten tribes of Attica. Scholars have argued the number of horsemen, chariot passengers, grooms and procession marshals number 192, the same number of Athenian dead at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC – thus immortalizing the fallen warriors and providing another powerful reference to the Persian Wars.

At the far end, the files of people and animals converged on the east frieze, over the main entrance, where the high priests were gathered, shown leaning on their staffs. The Olympian family of gods in the middle, some in relaxed poses while others in animated conversation, await the arrival of the Procession.

From olive presses and traditional costumes...

A once-mighty city-state overlooking Souda Bay,...

A 3D reconstruction by Oxford researcher...

Archaeologists at the site of Aghios...