Besides civic buildings, the Athenian Agora also provided basic amenities to the hundreds of people who congregated there each day. Two basic needs had to be met: water and shelter. Water was piped into two large fountain houses at the southwest and southeast corners of the square by means of subterranean aqueducts, usually made of baked clay. For shelter, the Athenians resorted to stoas. A stoa was any long colonnaded building, well adapted to the Greek climate and the needs of the people. The open colonnaded side provided good light and fresh air, while the roof and side walls provided protection from the sun in summer and wind and rain in winter. Stoas were often very large, capable of accommodating thousands of individuals, and they are found wherever many people were expected to gather: in sanctuaries, near theaters and particularly around agoras. The Athenian Agora had as many as six, two of which are of special interest.

THE PAINTED STOA (ca. 470 BC)

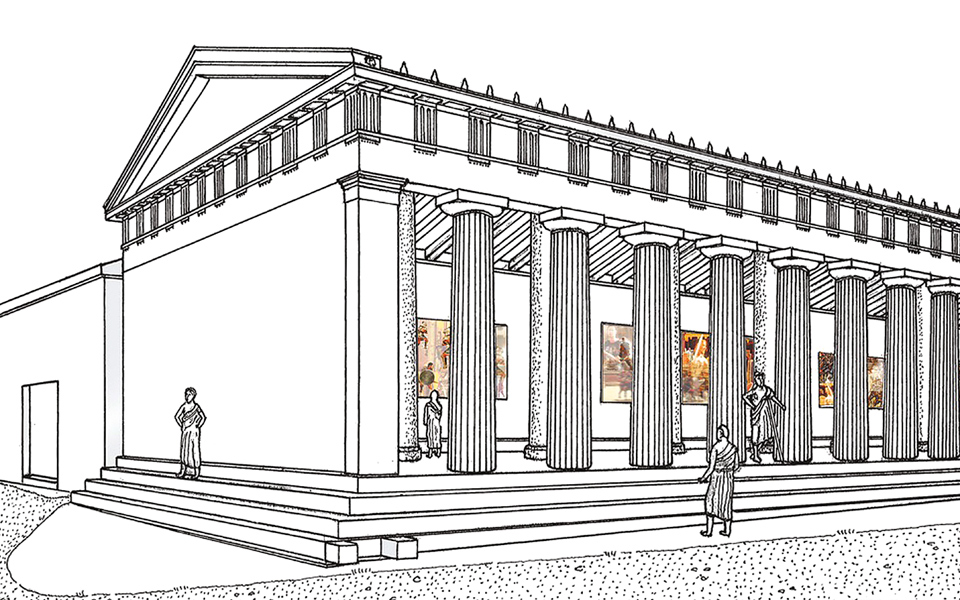

The most recent excavations, at the northwest corner of the square, across modern Adrianou Street, are bringing to light the remains of a stoa of the Classical period, dated to about 475-470 BC. It is 50 meters long, with a row of columns of the Doric order outside, and a row of Ionic columns inside. Less than a third of the building has been uncovered thus far. If we are interpreting the ancient sources correctly, especially the traveler Pausanias who described Athens as he saw it around 150 AD, then this building should be identified as the Painted Stoa, one of the most famous buildings of ancient Athens.

The Painted Stoa (Stoa Poikile) was built at the time of Cimon, the predecessor of Pericles. Soon after it was built, it was decorated with handsome paintings done on wooden panels and from then on was known as the Painted Stoa. In a sense, one can regard the stoa as the first public art museum. For centuries, magnificent art had been produced all over the Middle East, the Mediterranean and Africa; but it was not for everyone, just the elite. It decorated the king’s palace, the walls of temples with limited access, as well as tombs. In Athens, the art was displayed in a large open building, set right on the edge of the public square, where anyone and everyone was free to enter. The paintings went up around 460 BC and 600 years later, Pausanias could still describe four of them, showing Athenian military exploits, both mythological and historical: the Athenians fighting Amazons, the Fall of Troy, the Athenians about to engage the Spartans and — most famous of all — the Athenians defeating the Persians at Marathon in 490 BC. By 400 AD the paintings were gone. The bishop Synesius visited Athens at that time and was a bitterly disappointed tourist; having come to see the famous paintings, he found they had recently been removed by a Roman proconsul.

“ In a sense, one can regard the stoa as the first public art museum. For centuries, magnificent art had been produced all over the Middle East, the Mediterranean and Africa; but it was not for everyone, just the elite. ”

© Panayiotis Tzamaros

So we will not find the paintings; but the building has other interests. Unlike all the others around the Agora, the Painted Stoa had no specific function, nor did any magistrate or group of officials have priority of use. It was built and used as a hang-out and must have been the most public building of the city, full of Athenians with time on their hands. So anyone with a trade that required an audience would come to the Stoa, and we hear specifically of beggars, sword-swallowers and jugglers congregating there.

Another group who required an audience were philosophers, and when Zeno came to Athens from Cyprus around 300 BC he found the Stoa to be a useful place: he was allowed to use it, it was right on the central square and it was full of Athenians who were not too busy. Using it repeatedly, he and his followers became known — from their meeting-place — as the Stoics. So the remains coming to light constitute an important element in the development of western thought and philosophy.

“ Zeno found the Stoa to be a useful place: he was allowed to use it, it was right on the central square and it was full of Athenians who were not too busy. ”

“ The building dates from the Hellenistic period, a transitional time when Athens had lost all military, economic and political clout. ”

THE STOA OF ATTALOS (ca. 150 BC)

Another stoa in the Agora draws our immediate attention: the Stoa of Attalos II, reconstructed in 1953-1956 to serve as the Agora Museum. As one experiences it today, it provides an excellent sense of how an ancient stoa was meant to work, sheltering hundreds of people in an environment where the play of light and shadow inside changed constantly. The building dates from the Hellenistic period, a transitional time when Athens had lost all military, economic and political clout. Only in one sphere of influence did Athens remain dominant: education. The founding of the Academy by Plato (ca. 388 BC), the Lyceum by Aristotle (ca. 335 BC) and the Stoic school of philosophy by Zeno (ca. 300 BC) ensured that Athens was the educational center of the Mediterranean throughout antiquity, patronized by Hellenistic dynasts and then Roman nobility.

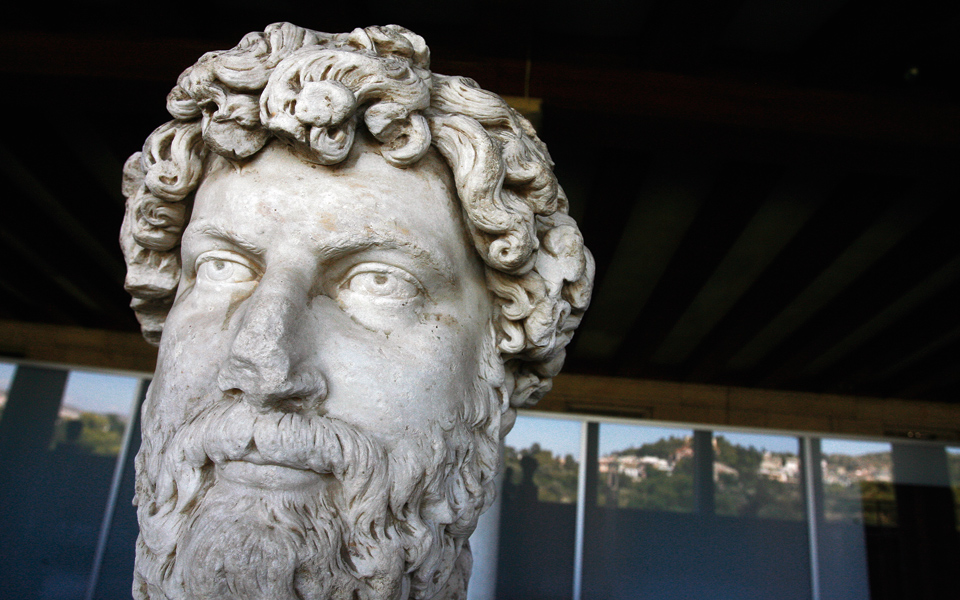

Such was the case of Attalos II, whose family ruled Pergamon, in what is now western Turkey. While still a prince, he came to Athens to study under the philosopher Carneades. Returning home and becoming king (159-138 BC), he gave the city this handsome stoa of marble, largely in appreciation of his happy college days in Athens. This is, in effect, an alumnus gift, of the sort familiar to anyone who has ever set foot on an American university campus, where every building carries a donor’s name.

What Attalos gave the Athenians was a fully developed stoa, with rooms added behind the double colonnade, and then the whole thing repeated on a second story. The rooms served as shops, rented out by the state, making the stoa the commercial center of the city for over 400 years. With 42 shops on two levels under a single roof, the building may well lay claim to being the world’s first mall. Not much has changed since antiquity except the technology.

UNCOVER THE PAST!

Excavations of the Athenian Agora by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens have been ongoing for 85 years. All the work, including the reconstruction of the Stoa of Attalos, the restoration of the nearby Church of the Holy Apostles, as well as the landscaping of the archaeological park, has been done with private American money, a reliable indicator of how much Americans admire and cherish the Greek roots of western society, politics and art.

If you would like to participate in the ongoing work of recovery of all periods of Athens’ past, please contact the ASCSA at 6-8 Charlton St., Princeton, N.J. 08540 or go to: www.ascsa.edu.gr/index.php/giving