4 Exhibitions to Discover at the Benaki Museum...

From sculpture to silent movement, explore...

Ioannina, 1898. Members of the Levis family in front of the home occupied by one of Nissim's brothers, Matathoulis Levis (seen far left holding his son Sam by the hand). The home still stands today.

© Courtesy of Kapon Editions

The war has just ended. Members of a family of Greek Jews who had escaped the worst of the Nazi occupation by hiding near Athens return to their home city of Ioannina, searching for traces of their old life. But they find a different reality. The majority of the city’s Jewish population has vanished and of their grand, three-story home on Kountouriotou Street, built in the local architectural style of the early 19th century, only the stone outer shell remains. The rest is burnt and looted.

As they return devastated to their hotel, they see on a salesman’s bench a Taxiphote Jules Richard slide viewer. Upon looking at the stereoscopic images in the viewer they realize that they were all taken by their relative, Nissim Levis, who in 1944 was among the Jews of Ioaninna transferred to Auschwitz. He was not among those who were rescued by Soviet forces when they freed the camp on January 27, 1945, a date that became established as International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Ioannina, ca 1905. Nissim D. Levis out hunting on the lake of Ioannina, pictured with the Aslan mosque in the background.

© Courtesy of Kapon Editions

In total there were about 500 images in the form of glass photographic plates, which were passed down in the family until Alexander Moissis, the grandson of Nissim Levis’ niece, decided to share this family heirloom with the world. And so, following a painstaking process, the glass plates that survived destruction almost by chance, were processed and categorized and assembled into an exceptional book published by Kapon Editions titled, The Nissim Levis Panorama, 1898-1944: Stereoscopic photos and travels of a doctor from Ioannina. In 2017, the Academy of Athens awarded Alexander Moissis a Prize in the Section of Letters and Fine Arts for the book.

The story begins in the last years of Ottoman rule in the western region of Epirus, after which we travel to Montpellier and Paris where Nissim Levis studied medicine. He later returned to Ioannina where he opened his own practice and we observe the city during the Balkan Wars, life and travels during the interwar period, up until the Second World War when, as the renowned historian Mark Mazower notes in the prologue, “the world that Nissim Levis knew, and recorded and hence allowed us to glimpse, the world of the European bourgeoisie, vanishes.”

Nissim's brother Matathioulis Levis (second from left) with friends on the lake.

© Courtesy of Kapon Editions

“Some of these photographs I remember from my kindergarten years,” Moissis told us. “They were stored in a cupboard in the study in my grandparents’ house. When my grandfather had a visitor and wanted to speak to them in private, he would ask my grandmother to take us to his office and show us the ‘kratidor’. This strange word was a code between them and it meant ‘keep the kids here’. Because every time they would send me to the study I would play with the glass photos, I thought ‘kratidor’ was the name of the viewer. To this day that is still how I refer to the big wooden box.”

Today Moissis lives and works in Silicon Valley. The book of Nissim’s Levis’ photographs is the result of him dedicating the countless hours needed to ensure the memory of his relatives would be something more than ‘a list of names on the holocaust memorial’, as he writes in the introduction.

“There were times, as I scoured the past, when I wondered how Nissim Levis would feel if he knew that I had published his collection, uncovering a part of his life and putting on public display. I want to believe that he would not object to it. It is better that the memory of these people be connected to their beautiful life, and not only to their brutal and inhuman deaths.”

Ioannina, summer 1912. Members of the Levis family pictured in the back yard of their house. The little girl holding the gun is Hiette Levis, Nissim's niece and the author's grandmother.

Ioannina, February 21, 1913. Nissim Levis captures the historic moment when the first Greek armed forces paraded into the city of Ioannina following the unconditional surrender of the Ottoman ruler, Essat Pasha.

© Courtesy of Kapon Editions

Ioannina, summer of 1913. Another piece of Epirus history captured by Nissim. Aggelos Typaldos Forestis, then district governor of Ioannina (later governor of Epirus) jokingly points a gun at Konstantin Bilinksi, a representative from Austria appointed to the international committee to determine the Greek-Albanian border.

© Courtesy of Kapon Editions

“Every photograph hid its own story,” Moissis says. “And every act of recovering these stories from the depths of the past brought not only the technical satisfaction for having solved a problem, but was particularly moving for having discovered one more facet of the life of Nissim Levis, of my grandmother and other ancestors.” Here (in the top photograph above) we see the courtyard of the house in Ioannina in the summer of 1912. The gun-wielding girl who is the focus of the photograph is one of Nissim’s nieces, Hiette Levis, the author’s grandmother.

At the Zollikofer residence in Nancy, circa 1901. Nissim and his friends and other banqueters enjoy a lavish dinner and amuse themselves with poems, music and wide-ranging conversations.

© Courtesy of Kapon Editions

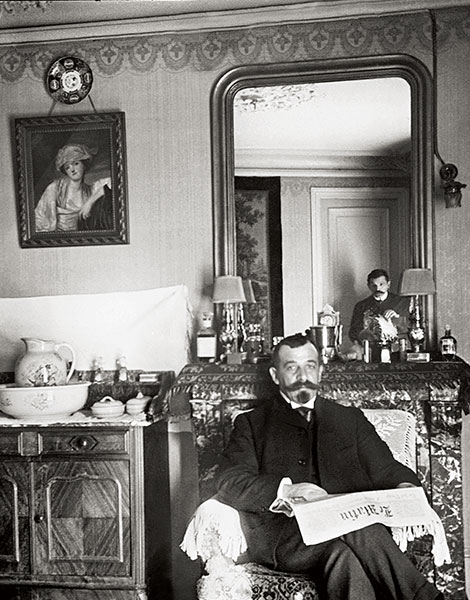

Paris: Sunday February 21, 1909, in the apartment of Nissim's brother, Maurice D. Levis. Nissim is visible in the mirror.

© Courtesy of Kapon Editions

Nissim Levis left for France, to study medicine at the end of the 19th century. He experienced first-hand the famous World Fair of 1900 in Paris, was a guest in French dining rooms (in the photograph above we see Nissim and his friends enjoying a feast at the home of an affluent Parisian family), took walks around the Jardin du Luxembourg and the Bois de Boulogne. He got to know western Europe, passed by Marseilles and Naples, traveling as far as the Pyrenees and the Alps.

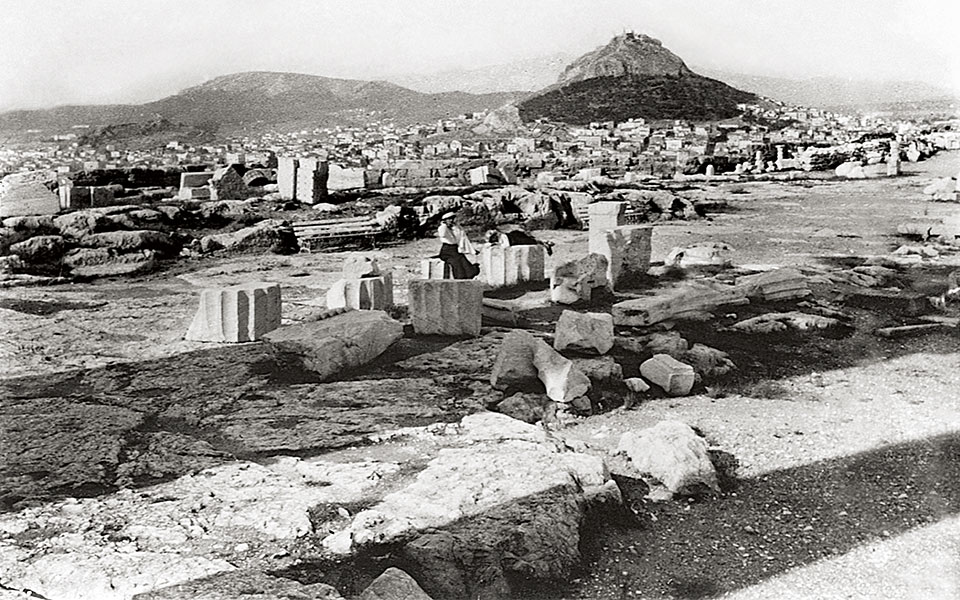

Acropolis, Athens, June 1923. Nissim's nieces, Hiette and Nelly Levis (aged 17 and 12) at the Acropolis.

© Courtesy of Kapon Editions

Vittel, France, August 1927. Nissim (far left), his niece and nephew Hiette and Sam, and his brother Maurice (far right) at the Grand Hotel du Parc, (now Club Med Vittel le Parc).

© Courtesy of Kapon Editions

When he completed his studies in 1904, he returned to Ioannina, where he opened his medical practice and, as Moissis writes, became particularly popular for devoting one day of the week to treating the poor free of charge.

But he did not stop traveling and returned to Paris a number of times to see his brother, Maurice (in the photograph above, Nissim can be seen in the mirror), who lived there. From the headline of the newspaper “Le Matin” that Maurice is reading, the precise date the photograph was taken could be established: Sunday, February 21, 1909.

Ioannina, February 1929.

© Courtesy of Kapon Editions

“I began identifying locations, with the aid of Google’s search tools,” Moissis explains to us. “It became my hobby and every day, after work, I would analyze 2-3 photographs. After identifying certain locations, I began establishing who the people were and when the photograph was taken. From the age of my grandmother and some other individuals I started to piece together the timeline of the life of the photographer. That in turn assisted identifying locations in some other photographs. And so on.”

In the photograph above we see the frozen lake of Pamvotida. It is February of 1929 and Moissis notes in the caption that the particular photograph was easy to date, as the lake rarely freezes over. The strange landscape makes it look like time itself has frozen. But, unfortunately, that did not happen. 18-year-old Nelly, one of Nissim Levis’ nieces who we see standing front and center, was destined to die some years later in Auschwitz.

Ioannina, March 25, 1944, near Mavili Square, less than 200m from the Levis house. The final image of the book and the only one not taken by Nissim Levis (he too was deported that morning). A few days later he and many other members of the Levis family were executed at Auschwitz.

© Courtesy of Kapon Editions

The last photograph in the book was not taken by Nissim Levis. Those pictured are Greek Jews in Ioannina getting on the truck that will take them to the train for Auschwitz. At the same time another vehicle was taking Nissim to the same destination. The chilling scene above took place near Mavili Square in Ioannina, not far from the Levis’ home on March 25, 1944.

“When I was small and looking at the photographs, it never crossed my mind that the majority of the people picture later suffered terrible deaths,” Moissis says. “Of course I knew about the Holocaust, the one or two times a year that I was taken to the synagogue, I looked with awe at the elderly people there, wondering how they had borne such loss. But I don’t remember a conversation on that subject with my grandfather and grandmother about her family. It was only much later that I realized that the stories from her childhood that my grandmother would tell us when I was a small boy on her knee was for her the least painful way for her to remember her past.”

The Nissim Levis Panorama is available on Amazon here.

From sculpture to silent movement, explore...

From olive presses and traditional costumes...

With fewer tourists, sunlit harbors, and...

Unexpected discoveries and timeless classics. Everything...