Picture this. It’s late June 1963. An American girl, so impatient to get to Europe that she skips her college graduation ceremony, sets off from Paris in a VW Beetle with her younger brother for company, and drives to Greece through Northern Italy and Yugoslavia.

They’re in such a rush to get to the Aegean islands, that they pause only for a cursory wander round the Piazza San Marco and the medieval city of Dubrovnik. When, after little over a week, they cross the border into Greece, farmworkers returning home from their fields wave to them from brightly painted horse-drawn carts.

After a few days on their first island, Spetses, where the girl has a friend from college, her brother dashes her plans for island hopping, declaring that old stones hold no interest for him, and since they’ve found the perfect place, why move? His refusal to budge changes her plans and instead they are adopted into a “parea” of young international Greeks.

They are utterly spoiled by their friendship – picnics with keftedes (minty meatballs) instead of sandwiches, their open homes and jasmine-scented terraces, a spit-roasted lamb BBQ party on a beach overlooked by The Magus’s house . . . So spoiled that when they eventually tear themselves away and visit the already legendary Mykonos, they discover it is no fun being “an ordinary tourist.”

When her brother leaves to go back to college, she sails off to Crete to see where the Minotaur lived and finds herself invited to a village wedding and eating tiny snails with a toothpick in the shadow of the Venetian fortress on the port.

After three months she returns to Paris (this time with college boyfriend) and spends the year there. But so enamored is she with Greece that she listens to Bithikotsis sing Theodorakis more often than Piaf and Aznavour, while mooning over La Grèce que j’aime, a book of B&W photos given to her for Christmas.

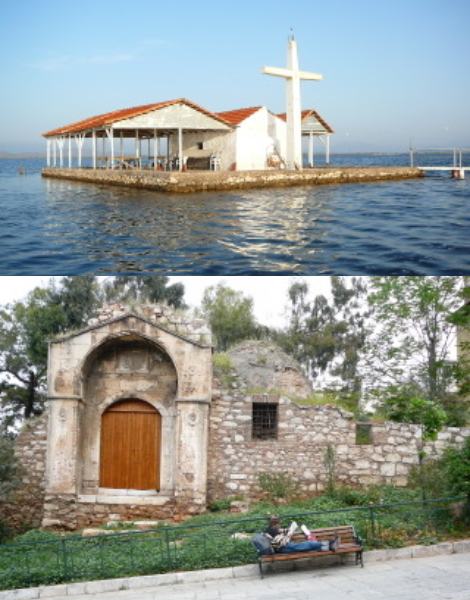

© Personal archive of Diana Farr Louis

© Personal archive of Diana Farr Louis

The following autumn finds her back on Spetses with the Greek she will marry in New York eight months later, captivated and horrified by the stories he and his mother tell of WWII, and learning expressions like “hara theou” (“a joy of God day”), when everything is so clear and shining that even God is delighted.

She spends part of her extended honeymoon on Spetses, wrapped in love by her husband’s family and learning to use the speargun he gave her for a wedding present instead of a diamond ring. The family is anything but typical. All of them live abroad, in Paris or London, except for her mother-in-law, who announces that she has no intention of playing that role and will be her friend instead.

While it’s true that Spetses in the Sixties attracted ambassadors and authors, famous journalists, socialites and celebrities – Vivien Leigh, Melina Mercouri, Greta Garbo, to name a few – in those days wealth and fame were not as important as being able to tell a story, make people laugh or collect and open sea urchins.

Sophisticates hobnobbed with boatmen and carriage drivers, snobbery did not exist, and she learned a new word, “kefi,” that seemed to mean more than mere joie di vivre and included exuberance, spontaneity, warmth and generosity.

© Personal archive of Diana Farr Louis

© Personal archive of Diana Farr Louis

She had never witnessed anything like it, neither in Spain, Italy or Paris, and certainly not on Long Island where she grew up in a society organized into different clubs for tennis and golf, sailing, and the beach. And while she had loved the Atlantic Ocean, she did not miss the endless stretch of sand, having her toes nibbled by unseen crabs, and the self-imposed division of club members by age group and even school class.

She spent almost every summer on Spetses, joined by her son, until her marriage broke up in 1970. Two years later, she moved to Athens, telling her ex that she was going home to mother, his mother.

She and her little boy were offered the family house in Marousi and when they arrived on June 6th, the neighbors turned out to welcome them – with food, with sheets and towels, and huge smiles. One of them even found her Christina, a woman from Ikaria who lived nearby, to help with the housework and babysit.

Christina became her “mother-in-law,” correcting her halting Greek, introducing her to divine dishes like cumin-flavored soutzoukakia (Smyrna meatballs) with tomato sauce, lachanodolmades (cabbage rolls) and prassorizo (rice with leeks). She also called her straight hair “prassa” and brought them milk from her goat, Asproula.

In the fall, she showed her how to pick their olives, and when they took them to the press in Marousi, she translated the owner’s remark, “Fae ladi ki ela vradi” (eat some oil and come round in the evening), which he said with a grin and a wink.

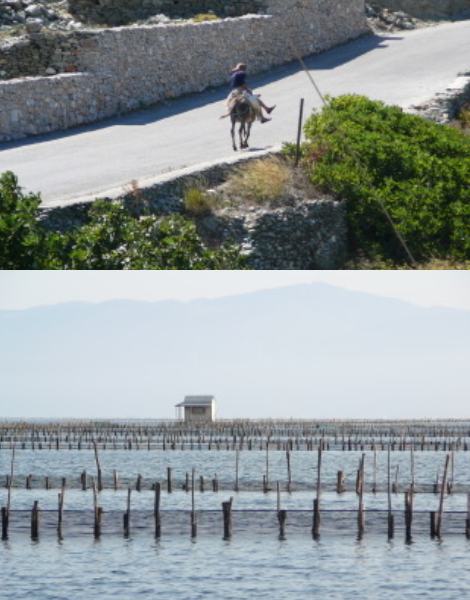

© Personal archive of Diana Farr Louis

Meanwhile, the ex New Yorker was discovering Greece, traveling to Hydra, Andros, Patmos and Samos, to Elefsina and Delphi, and joining a mountain climbing group called Ypaithria Zoe (Open-Air Life). Here again she found a warm welcome; though most of the members were older, they were kind and she loved the adventure, ascending mountains in the Peloponnese, even Taygetos.

Exploring became her passion, and her tiny Fiat 500 took her and her son to far-flung places to explore Crusader castles and Evia, where Christina’s sister astonished her by living in a one-room house with only two beds, which the family of five shared on a rotating basis. The two boys and their father worked nights. Her mouth had been touched by Midas though. All her teeth were gold.

In the course of her travels, whether next door or days away, she learned that you could not enter a Greek home without being offered something as soon as you entered – a cup of syrupy coffee, a loukoum or biscuit, a glass of cold water. Greek housewives put her to shame.

And later she would discover, in the course of researching a cookbook on Crete, that there hospitality had no limits, that Kazantzakis’ words from Report to Greco were not fiction: “In Crete the stranger is still the unknown god. Before him all doors open and all hearts are opened.”

© Personal archive of Diana Farr Louis

© Personal archive of Diana Farr Louis

Years before she had come to think of Greek food as “soul food.” Though she had been brought up “privileged,” on a regime of meat and two veg for dinner, fish on Fridays and roast beef, lamb or chicken on Sundays, she had never even seen a lentil or a dried bean, much less dreamed of feasting on squid and octopus.

Rice was not a pilaf with a vast repertoire of additions and seasonings, but came straight out of an Uncle Ben’s box; soup was mostly Campbell’s Alphabet; and vegetables were mostly just boiled with a little butter on top, not something luscious that had been stewed, stuffed or baked.

Olive oil? Not an ingredient anyone on Long Island had ever heard of. Not even her mother who grew up in Italy and used corn oil to make her one dish, spaghetti with meat sauce.

As she came to know all the wonderful foods of her adopted country, the regional differences, the spicy tastes brought by the refugees from Asia Minor, the huge variety of vegetable dishes and the amazing “fasting fare” of Kathari Deftera (the beginning of Lent), she realized she’d grown up deprived.

She also realized that sometimes the best meal you ever eat is the one you don’t expect: fried eggs, fried potatoes and a tomato salad when you’ve been hiking on Naxos until famished, or driving up the Kavo Doro coast of Evia in the dark, not knowing whether to push on or head back to Karystos, and finding a taverna (and a bed) at the last minute.

As she traveled round Greece, on friends’ sailboats, by car and by foot, accompanied by the love of her life, she got to know virtually every island and every region (except for the Holy Mountain).

She wasn’t sure that she knew exactly what George Seferis meant when he wrote, “Opou kai na pas, i Ellada se pligonei” (wherever you go, Greece wounds you), but Greece wounded her with its excessive and diverse beauty, its “joy of God days” and its fierce storms, the random acts of kindness of the strangers she met, the people who took her in when she knocked on their door seeking recipes, its layers of history – from the scars of the Civil War in Prespes and Agrafa, the unfinished legacy of Capodistrias in Nafplio and Aegina, Byzantine churches, Venetian castles, and Turkish mosques, a sign on Mt Oiti saying “Hercules’ funeral pyre,” even the weather with its Halcyon Days and Aeolos still blowing meltemia from his palace on Tinos, suggesting that some things are constant.

So after getting to know Greece for almost sixty years, she thanks her brother for not wanting to leave Spetses that long ago summer. And when people ask her how her experiences in Greece have changed her, she can only reply, “Greece didn’t change me. Greece made me: gave me two husbands, two families, lifelong friends, and a purpose to my existence – to write about it and share with others a hint of the bounty it has bestowed on me.”