The Many Faces of the Greek Gods

From temples and festivals to front...

The Rimondi Fountain (1626), which supplied Rethymno with cool water from Mt Vrysinas.

© Shutterstock

A few years ago, I found that, with one 25-year-old exception [i], there is no general history of Crete written in English. I therefore decided to write an outline of Cretan history which, while providing a serious treatment of the subject, would be readable and encourage readers to dig deeper. [ii]

Crete has a complex, fascinating and varied 6000-year history, and yet almost all attention has been focused on the Minoan period and the Battle of Crete in 1941. The 3000 years between these periods has been largely ignored. I felt that there was an imbalance here that needed correcting. I hope that this brief article will whet your appetites for the complete book.

Remains from the Minoan period at the archeological site of Knossos.

© Shutterstock

The history of Crete has been influenced by three factors: landscape, location and the character of the Cretan people.

“Round him spread his native country. … Hard of approach, rebellious, harsh was this land. She allowed not a moment of comfort, of gentleness, of repose. Crete had something inhuman about her. One could not tell whether she loved her children or hated them. One thing was certain: she scourged them till the blood flowed.” [iii]

Nikos Kazantzakis thus describes in emotional terms the effect of the landscape on the Cretan soul, and it is certainly true that the geology of the island has played its part in shaping the history, society and economy of what has been called “a tiny continent”.

The mountain ranges effectively cut off much of the south from the north. The "mitata", round stone shelters, were used in the mountains as protection from the strong winds.

© Shutterstock

Four mountain ranges effectively cut off much of the south from the north and, as a result, for much of the history of the island, the major cities and most of the population were concentrated on the north coast. In the south – with a few exceptions – agriculture was largely limited to a subsistence level. Moreover, along much of the south coast, steep cliffs made access difficult if not impossible, and there were few natural harbours. As for the interior, even up to relatively modern times, overland transport was limited to mule paths, so that any area without good access to the sea was isolated. From the Cretans’ point of view this difficult landscape had its advantages, in that many areas of the island were inaccessible to conquerors such as the Romans, Arabs, Venetians, Ottomans and the Third Reich.

The Roman Odeon of Gortys

© Shutterstock

Another major influence on Crete’s history has been its location. Close to the junction of three continents, Crete has always been of major strategic importance. This has occasionally been to the island’s advantage; for example, during the Bronze Age, it was an ideal location for a seafaring trading society.

However, more often, Crete has attracted the attention of foreign invaders, not to mention pirates. For the Romans and the Venetians, the island was an ideal stopover for the trade routes to Africa and the Middle East; for the Ottoman Empire Crete, gave them complete control over the whole eastern Mediterranean; to the Third Reich, it would become an “aircraft carrier” for attacks on Egypt, Cyprus and Palestine. Much of the island’s troubled history has revolved around how the Cretans dealt with these conquerors and the influence of foreign rule on their culture.

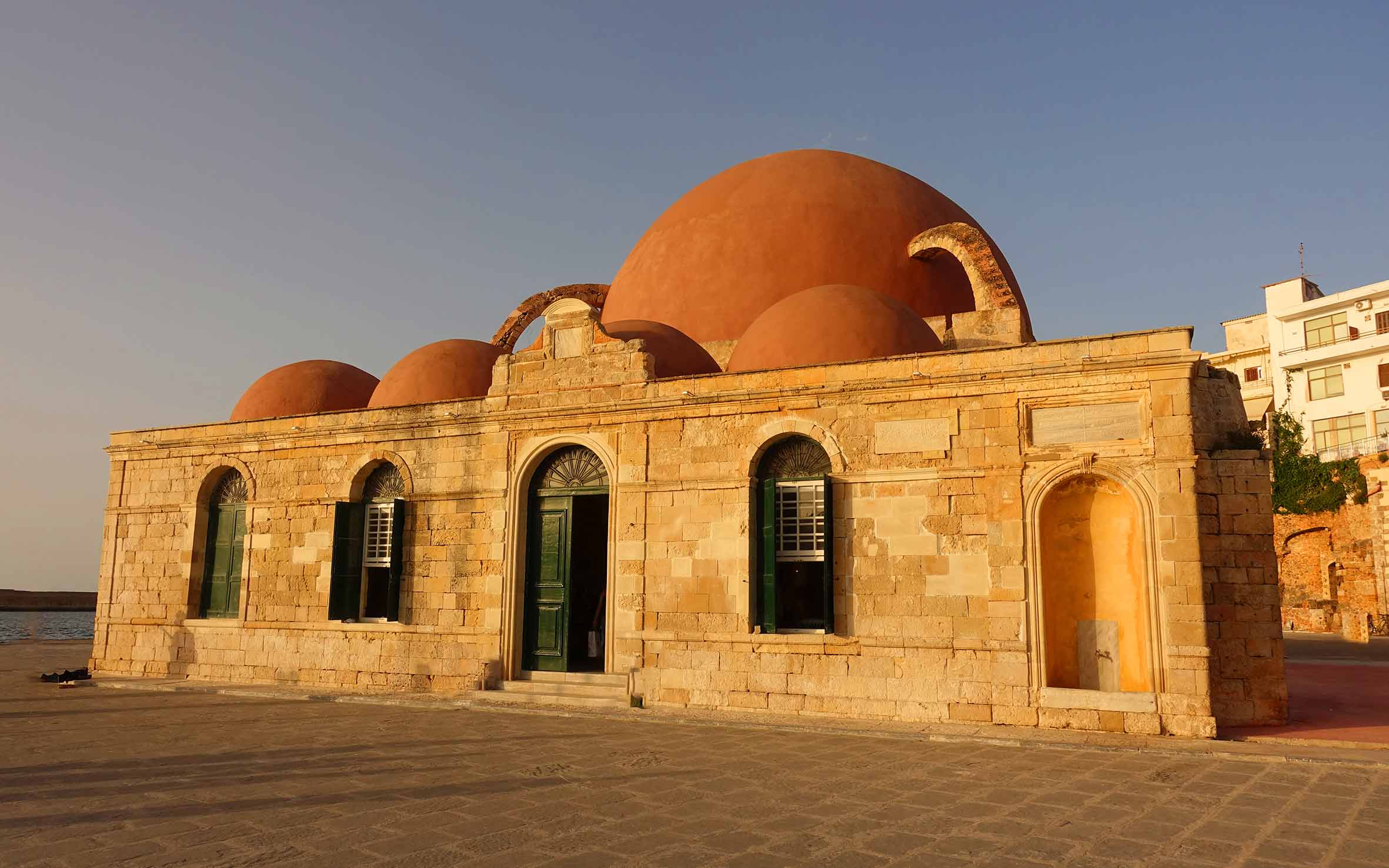

The “Mosque of the Janissaries” (aka Yali Mosque), in Hania, the oldest Islamic structure in Crete.

© Shutterstock

Cretan reaction to the conquerors varied. During the long periods of foreign rule, the Cretans developed an ability to absorb the good things the invaders brought and reject the rest, to tolerate them up to a point but to revolt if their rule became too harsh.

Thus, when the Romans invaded in 69 BC, there was fierce resistance but, once the island had been subjugated, Crete settled down to a peaceful and prosperous life as a small and largely unimportant part of the Roman Empire. This continued into the island’s time under the Byzantine Empire and, in fact, the Cretans regarded themselves for many hundreds of years as Byzantines.

The Frangokastello, built by the Venetians in 1371-74.

© Shutterstock

Things were completely different under the 440 years of Venetian rule. The harsh treatment of the Cretan population led to almost continuous rebellions. However, as the threat from the Ottoman Empire increased, relations between the Cretans and their Venetian rulers moderated, leading to cross-fertilization between the two cultures and a resurgence in art, music and literature, often called the Cretan Renaissance.

With the conquest of the island by the Ottoman Turks in 1645, all this came to an end. Like the Venetians, they quickly established complete control but, with the exception of one failed rebellion in 1770, resistance was small scale and spasmodic for the first 180 years.

The 19th century changed all that, with six rebellions of varying degrees of support and seriousness between 1821 and 1898. Even after the Ottomans left, during the brief period of autonomy for Crete, rebellion was still in the air, although this time the Theriso revolt of 1905 was a fight not for independence but for union with Greece!

Hania

© Shutterstock

In spite of, or perhaps because of, the repeated invasions and the harshness of the landscape, Cretans have developed a unique character, manifested over the years. First of all, they nurture a fierce patriotism and love of their island. Along with this love of their motherland, two other loves exist in the Cretan soul: a love of freedom and a love of life. Whether it be in the defiant resistance to Venetian rule or in guerrilla warfare against the Nazis, the Cretan battle cry throughout history has been that of the nineteenth-century rebellions against the Ottomans: Eleftheria i Thanatos (Freedom or Death).

As for love of life, it is as visible in the colourful and joyful Bronze Age frescoes as in the dancing at any party in any village in the twenty-first century.

To sum up, in the words of a modern mantinada,

Όσο θα στέκει να κτυπά ήλιος στον Ψηλορείτη,

Θα στέκει και θα πολεμά και θα γλεντίζει η Κρήτη

As long as the sun rises over Mount Psiloriti,

So long will Crete stand up to fight and to party. [iv]

[i] Professor Theocharis Detorakis, History of Crete

[ii] Chris Moorey, A History of Crete

[iii] Nikos Kazantzakis, Captain Michalis (known in the UK as Freedom and Death)

[iv] Mantinada by Yiorgis Karatzis, in the Lychnostatis Museum, Chersonisos

Chris Moorey is a writer and historian, and the author of A History of Crete, the first complete history of Crete to be published in English for over twenty years, and the first written for a general readership. He has lived in Crete for over twenty years.

From temples and festivals to front...

This spring, five majestic peaks across...

A once-mighty city-state overlooking Souda Bay,...

From historic landmarks to edgy street...