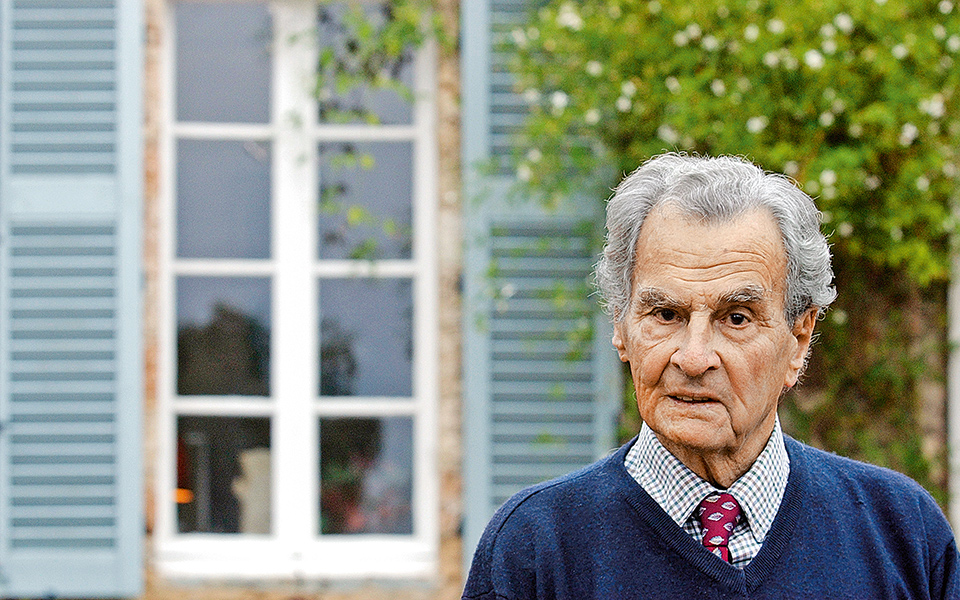

When people talk about Patrick Leigh-Fermor, they often use superlatives: “the greatest British travel writer,” “the most daring wartime secret agent,” “the last great romantic.” I first met him when I came to the Peloponnese to do research as an anthropology student nearly 30 years ago and I went to stay with him in Kardamyli. Although I then knew little about his life, I was, like so many, immediately won over by his charisma. Paddy, as he was always known by English friends (Greeks called him Michalis, his nom de guerre), lived with his wife Joan in a house just outside Kardamyli that they built in the 1960s. At that point, Mani was still an extremely remote, even wild corner of Europe – the inaccessible middle peninsular of the Peloponnesian three-fingered “hand,” with its striking stone towers reflecting centuries of blood feuds and the dramatic, rocky landscape of Mount Taygetus.

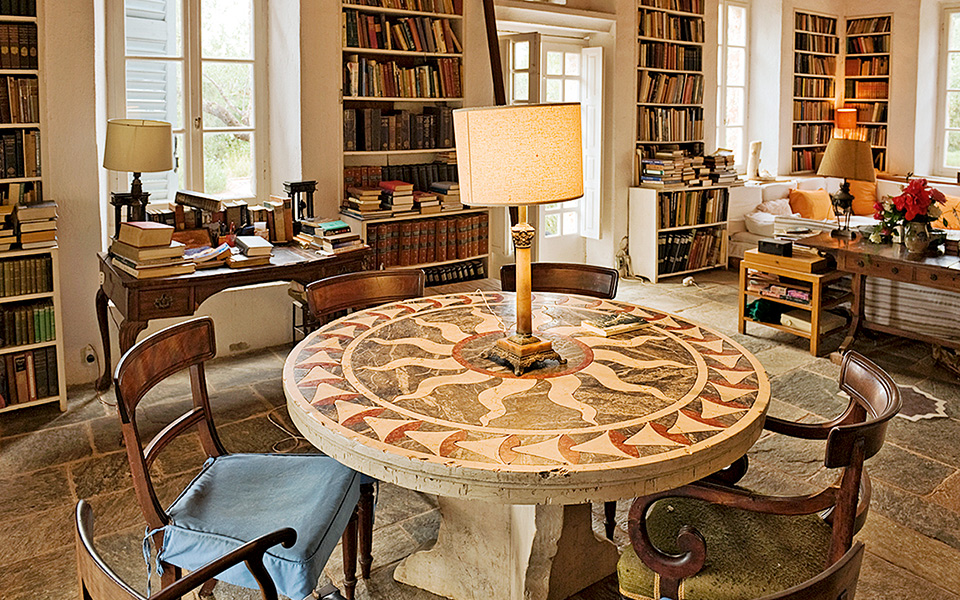

The couple gradually created their remarkable home – a mix between a Byzantine monastery and an English country house: carved stone arches, comfortable armchairs, walls covered in books and paintings by Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas. Cats (and sometimes goats) prowled over the beautifully designed stone terraces with paths made from smooth pebbles. They had picked their spot carefully – close enough to Kardamyli to have neighbors, shops and a few tavernas, but isolated enough to have the peace they desired. Steps lead from the house down to a beautiful little cove from which they and their friends would set out on long swims. And all around them, olive groves.

“ Patrick Leigh-Fermor and his wife Joan lived in a house just outside Kardamyli that they built in the 1960s, at a time when Mani was still an extremely remote, even wild corner of Europe. ”

© Nikos Kokkas

© Nikos Kokkas

“ During the war, Paddy served in the Intelligence Corps and helped organize the resistance to Crete’s Nazi occupiers. In 1944, using German uniforms as disguises, he and a group of Cretans kidnapped the Nazi chief of staff on Crete, General Kreipe. ”

Over the years, Paddy became a friend, and I gradually read all his books and learned more about him – the fast living that recalled his hero, Lord Byron, and the daring and resourceful- ness that conjured up a modern-day Odysseus. Wonderfully handsome as a young man, he was always beautifully dressed and remained charming, witty and courteous to the end. A man of action and of letters, Paddy was just as comfortable in grand English drawing rooms or mountain shacks in Crete and he was irresistible to women. A BBC journalist once described him as a mix between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene.

Paddy was one of the most cultured people I have met – constantly interested to learn about the people and places he encountered. He not only read literature and poetry but adored reference books. At dinner in Kardamyli, he would jump up to find a dictionary to illustrate a point or an atlas to locate the precise name of something.

An autodidact, he didn’t attend university, but in 1933, aged 18, walked across Europe. Carrying only a rucksack, he started in Holland and made his way through Nazi Germany, Hungary and on to Constantinople.

During the war, Paddy served in the Intelligence Corps and helped organize the resistance to Crete’s Nazi occupiers. He grew a large mustache and dressed as a shepherd with baggy pantaloons and a dagger in his belt. In 1944, he devised a bold, even crazy plan that has fascinated people ever since. Using German uniforms as disguises, he, Billy Moss and a group of Cretans kidnapped the Nazi chief of staff on Crete, General Kreipe. Living in remote caves, they avoided detection for two weeks, ultimately escaping with him back to Egypt.

© Julia Klimi

It was in Cairo that Paddy met Joan, a tall, blonde intellectual and photographer, the daughter of Viscount Monsell. The pair traveled together – in the Caribbean in 1949 (resulting in Paddy’s first book, The Traveller’s Tree) and then in Greece. In Athens they became friends with many artists and writers of the day, including Giorgos Seferis and Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas, and discovered Greece on foot and by mule, bus and boat. These explorations are described in Paddy’s two masterpieces, Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese and Roumeli: Travels in Northern Greece. Richly erudite but also humorous and anecdotal, they remain among the best things written about Greece by a non-Greek. Mani is also a eulogy to the place that Paddy and Joan chose as the ideal place to make their home. Although it was one of the most inaccessible parts of Greece, they quickly became friends with many of their neighbors and there was a stream of visitors from Athens, England and around the world. By the time he died aged 96 in 2011, Paddy had been awarded medals and honors by both the Greek and British governments (he was knighted in 2004). He left the house at Kardamyli to the Benaki Museum, with the intention that it should be used as a writers’ retreat.

Characterized by contrasts, Paddy was playful and scholarly, he drank impressive quantities and could sing folk songs in countless languages, but he regularly went into silent retreats at Cistercian monasteries. Set between the silvery olive groves of Mani and the lush, green fields of Worcestershire, Paddy’s remarkable life would be almost unbelievable in a novel: walking across Europe, falling in love with a princess, abducting a general, taking the best from Greece and England and becoming the finest travel writer of his generation.

Sofka Zinovieff is a British author • www.sofkazinovieff.com

“ Almost 50 years after it was first published, Leigh-Fermor’s book “Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese” remains one of the best ever written about Greece by a non-Greek. ”