Mention “architecture” to a visitor to Athens, and the first image to spring to mind will likely be the Parthenon. The marble edifice perched atop the Acropolis dominates the city below, both literally and figuratively. To the frequent visitor or more jaded local, the second association that might occur would be the pervasive polykatoikies – literally “multi-houses” or apartment blocks – that dominate residential neighborhoods radiating from Kolonaki and Pangrati downtown and outward to the distant suburbs.

First appearing in the 1930s, these structures exploded in popularity from the 1960s onwards and spread across the city in a sea of white concrete and marble cladding. While important from the sociological perspective of evolving Athenian post-war urban life, few would find much architectural and historical interest in their monotonous proportions and façade, at least in their iterations over the past three decades. However, those who take the time to look will find, tucked between the ancient sites, the neoclassical consulates and the 1980s apartment buildings, more than a few gems of modernism: buildings brimming with the optimism of the era, ambitious in their embrace of new materials, techniques and design language.

Some of these, such as the National Hellenic Research Foundation and the Athens Tower, have been overlooked in part due to the timing of their construction (during the military dictatorship of 1967-1974), dismissed as “junta” projects. But the Greek architects responsible for these and other landmark post-war structures were largely products of, or inspired by, the Bauhaus school and seeking to invest Greek urban life with the international spirit of the times. Athens stood poised to become – for the first time since antiquity – a global cultural capital.

© Domes Index

© Yorgos Prinos

THE ATHENS HILTON

46 Vasilissis Sofias

The Athens Hilton opened its doors to the public on April 20, 1963. The inaugural celebrations were attended by Conrad Hilton himself, who proclaimed the new building “the most beautiful Hilton Hotel in the world.” A bold showcase of contemporary architectural ideas, the Athens Hilton seamlessly blended timeless local materials – such as marble from Mt Penteli – with cutting-edge modernism. The massive reliefs gracing the building’s façade, created by the noted mid-century artist Yiannis Moralis, tie the modern to the classical, depicting ancient and mythical themes.

The quartet of architects responsible for the building’s design were Emmanuel Vourekas, Procopius Vassiliades, Spyros Staikos and Anthony Georgiades. Vourekas was one of the busiest Greek architects of the era, with over 200 buildings to his credit, including many in nearby Kolonaki. A short walk from the Hilton sits one of his last major commissions, the Megaron-Athens Concert Hall, adjacent to the US Embassy.

At the time of the Hilton’s construction, the design pitted the left-leaning architectural establishment – who saw the building as a blot on the city’s 19th century neoclassicism and the grand classical heritage from which it derived – against the segment of the public that enthusiastically greeted the hotel’s opening as a breath of modernity, signaling Greece’s true emergence after the hardships of the war years. The Galaxy Bar atop the hotel, with its stunning evening views of an illuminated Acropolis, represented the pinnacle of urbane Athenian aspiration, creating a visual dialogue between the greatness of the Athenian past and its aspirations for the future. In 2004, the Hilton received a sympathetic makeover to coincide with the Athens Summer Olympics, overseen by architects Alexandros Tombazis and Charis Bougadelis.

© Yorgos Prinos

ATHENS TOWER

2-4 Mesogeion

The first glass skyscraper in Athens was designed by Ioannis Vikelas and Ioannis Kymbritis. Constructed between 1968 and 1971, the complex consists of two structures, the taller of 25 stories and the shorter of 12, linked at the first floor, with shops occupying the ground floor.

The structure utilizes glass curtain wall construction – echoing the pioneering international style of New York landmarks such as the UN Headquarters (Oscar Niemeyer and Le Corbusier, 1949) and the Seagram Building (Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson, 1958) – with brown anodized aluminum window sashes and white marble vertical cladding. This remains one of the tallest structures in Athens.

© Yiorgis Yerolymbos Project Chancery: Walter Gropius US Embassy in Athens

© Yiorgis Yerolymbos Project Chancery: Walter Gropius US Embassy in Athens

EMBASSY OF THE UNITED STATES

91 Vasilissis Sofias

The US Embassy in Athens, a landmark example of mid-century modernism, was designed by Walter Gropius, one of the most influential architects of the 20th century and founder of the Bauhaus school, together with Greek architect Perikles Sakellarios.

Opened to the public on July 4, 1961, the building attempted to capture the spirit of its classical antecedents and the Parthenon without being merely imitative; it features brilliant white Pentelic marble cladding, black marble from the Peloponnese and grey marble from Marathon, and a simple colonnade that wraps around the entire structure, while simultaneously presenting something entirely new with its cantilevered upper two floors.

The embassy was intended by Gropius as a metaphor for democracy itself, with its expansive courtyard designed to encourage people to linger, converse and debate ideas openly. Through his design, Gropius sought to create a direct link between democracy’s classical roots and the young American nation. Alas, the openness Gropius envisioned has had to defer to contemporary concerns; the novel outdoor landscaping has now given way to security fencing. A major rehabilitation of the building, to be overseen by Ann Beha Architects of Boston, Massachusetts, is scheduled for the near future.

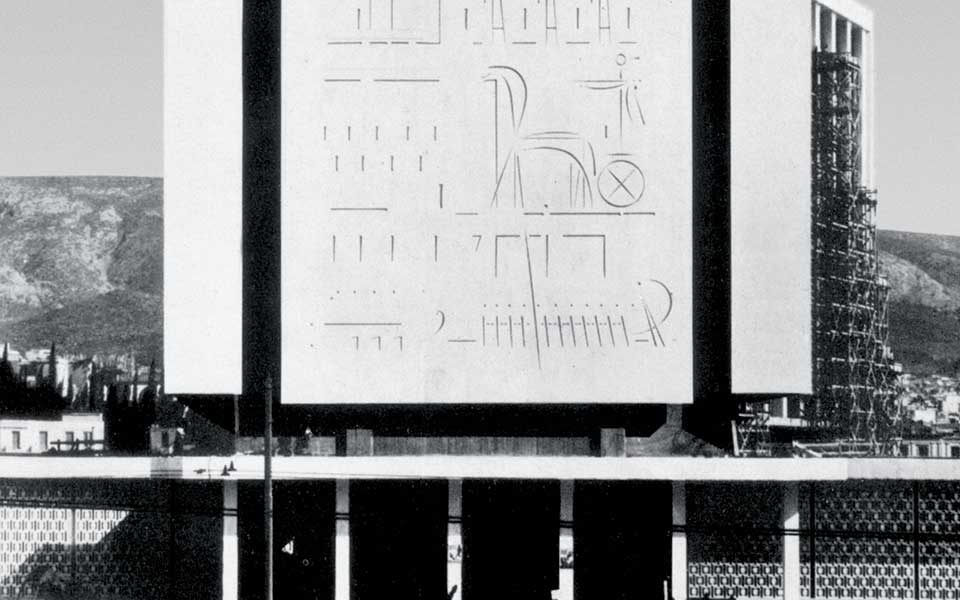

© Dimitris Kalapodas Archive/Domes Index

© Dimitris Kalapodas Archive/Domes Index

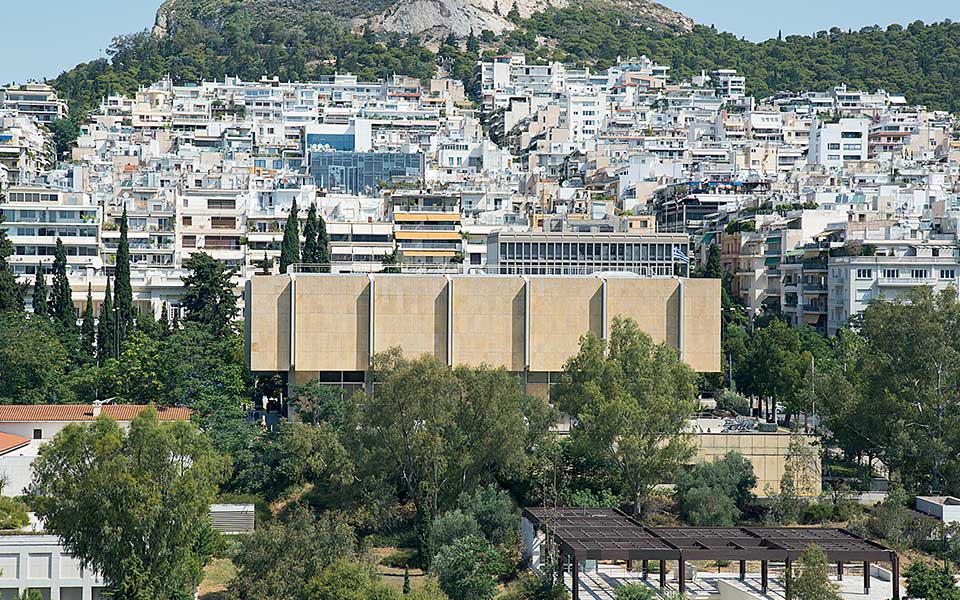

ATHENS CONSERVATOIRE

17-19 Rigillis and Vasileos Georgiou II Architect Ioannis Despotopoulos was the only Greek to study at the Bauhaus school under Walter Gropius. His liberal political beliefs and his association with the “radical” reputation of the Bauhaus movement resulted in a period of self-imposed exile in Sweden during the 1950s, where he worked under the name Jan Despo. It was from Sweden that, in 1959, he submitted the winning entry for an urban planning competition to design a new cultural center for Athens.

His vision was anything but modest: it was to encompass nearly 150,000 square meters, connecting the arteries of Vasileos Konstantinou to Vasilissis Sofias all the way to the National Gallery. In addition to the Conservatoire, it was to include a 1,800-seat opera house, an orchestra and ballet hall, a circular theater as well as a playhouse for experimental theater, an extension to the National Gallery, a new Byzantine Museum and a church. His goal was nothing less than to transform Athens into a world capital of culture. After delays and the submission of a revised plan in 1966, construction finally commenced, but further delays and cost overruns brought the project to a halt in 1976, with only the Conservatoire completed.

Although Despotopoulos was recognized as an architectural and planning visionary across Europe, the Athens Conservatoire is his sole completed project in his native land. The design is deceptively simple, a rectangular two-story box. The long, strikingly simple façade is pierced by openings affording views of Mt Lycabettus. Within, the building is a hive of activity, with music and voices from rehearsal spaces and practice rooms filling the hallways. In 2017, the Greek architectural firm Atelier66 undertook a project to restore, complete and enhance Despotopoulos’ original plan for the Conservatoire, with the financial backing of the Foundation of the Friends of Aliki Vatikioti for Music and the Arts.

© Yorgos Prinos

OTE HEADQUARTERS

99 Leoforos Kifisias, Maroussi

In 1971, Hellenic Telecommunications (OTE) held a competition to choose a design for its new Athenian headquarters. While no competition winner was chosen as such, the design submitted by a group of three academics was awarded the commission for the new building. The architects Platon Masselos, Grigoris Mavrommatis (current president of the Hellenic Handcraft Industry Association and Diplareios School) and Dimitris Nakos proposed a three-pointed star-shaped structure, some 21 stories tall and encompassing a colossal 64,785 square meters of floor space, resting on a building plot of some five hectares in the suburb of Maroussi.

Built at a time of massive expansion and modernization in the telecommunications industry in Greece, the building’s form and scale can be seen as a manifestation of national aspirations for a modern, technological future. Work began on the construction of the new headquarters in 1974 and was completed, after many delays, in the 1980s. The OTE complex remains the eighth-tallest structure in the country.

Recent years have seen the renewal of the original concrete cladding, as well as the renovation of the interior offices and the opening of a new restaurant on the building’s ground floor. Forty-four years after construction on the landmark structure began, it still serves as the Athens administrative hub of OTE, a testament to the scope, scale and vision of its original design.

© Yorgos Prinos

NATIONAL HELLENIC RESEARCH FOUNDATION

48 Vasileos Konstantinou

This building was designed by Constantinos Doxiadis, the father of ekistics – the science of human settlement – whose work principally focused on large-scale urban design. Doxiadis oversaw projects around the world, from Islamabad, where he was lead architect for the new Pakistani capital, to Detroit. At the time of the NHRF commission in 1962, his firm, Doxiadis Associates, employed some 400 people, half of whom were deployed internationally, while the other half worked from the Doxiadis-designed headquarters in Kolonaki (today the ONE Athens luxury apartment complex).

The NHRF project came at the suggestion of Dimitris Pikionis. The structure was the first Greek public building to embody the dictum of American architect Louis Sullivan that “form follows function.” It consists of three principal volumes: the six-story office building, the three-level library, and the entrance foyer and lecture hall. Faced with white and pink marble, the buildings project monumentality, in keeping with the foundation’s mission.

© Yorgos Prinos

NATIONAL WAR MUSEUM

2 Rizari

Cairo-born architect Thukydides Valentis showed exceptional promise as a student at the National Technical University of Athens, where he eventually served as chair of the School of Architecture. A partner in Valentis’ first architectural practice, Polyvios Michailidis had worked under none other than Le Corbusier.

Valentis was an unabashed admirer of modernism. This is particularly reflected in this commission for the National War Museum. Perhaps the most striking feature of the building is the juxtaposition of the larger first story above the smaller ground story, giving it the appearance of almost hovering above the ground, notwithstanding its bulk.

© Yorgos Prinos

THE ROUND SCHOOL – AGHIOS DIMITRIOS

23 Stratigos Papagou, Aghios Dimitrios

There is no Greek architect of the mid-20th century worthier of the epithet “visionary” than Takis Zenetos. He dreamed of cities built in the sky, tethered to pylons on the earth’s surface or suspended above the ground in a great net.

His design for the refurbishment of the Fix brewery on Syngrou Avenue in 1957 was groundbreaking, with simple, severe modern lines; the brewing operations were visible to the passing public through a solid wall of glass. In 1994, half of the then-defunct brewery was demolished to permit construction of the Syngrou-Fix metro station, and what remained was converted in 2016 into a home for the National Museum of Contemporary Art, with Zenetos’ original façade on Syngrou Avenue hinting at the original building’s monolithic grandeur.

Zenetos also developed ambitious plans for a theater atop Lycabettus, including a “temporary” 3,000-seat structure that opened to the public in June 1965 with a performance of “Antigone” by Sophocles. What was to have been temporary still remains in place today, but Zenetos’ design for a 5,000-seat theater and cultural complex atop the hill still remains unrealized.

His Round School in Aghios Dimitrios is a testament to his extraordinary talent. Designed in 1969, the school opened to students in 1974. The massive concrete louvers located on each of the school’s three floors were carefully shaped and positioned in order to optimize the amount of light entering the building over the course of the school day. Zenetos chose a circular shape both as a cost-saving measure and to enable future expansion of the school. The classrooms are located on the building’s perimeter, while the core contains media facilities. Deeply functional, yet imaginative and otherworldly, the Round School represents a creative evolution of Bauhaus principles.