Aigai: The Mysteries of Philip II’s Restored Palace

Aigai’s newly restored Macedonian palace represents...

Youngsters by the sea, a rare photograph by prolific mid-20th century Thessaloniki photographer Socrates Iordanidis, from the archives of the Museum of Photography.

© Socrates Iordanidis / Thessaloniki Museum of Photography

“No man will be without a homeland, as long as Salonica exists,” so wrote Nikephoros Choumnos, the Byzantine scholar and statesman (Grand Logothete) of Thessaloniki, as early as the 14th century AD. This sentence captures the essence of a city located midway between the East and West, at the intersection of cultures; a city that is a geopolitical keystone, a bustling crossroads, a haven for the poor and persecuted, and one of the few European cities to an uninterruped urban population across 2,500 years.

Thessaloniki was founded by Cassander, the King of Macedonia, in 315 BC. He consolidated the population of 26 surrounding settlements within the walls he raised around the new city, which he named after his wife, the sister of Alexander the Great and daughter of King Philip II. The dazzling palaces and public edifices he erected were instrumental in Thessaloniki’s metamorphosis into the most important port city of the Macedonian Kingdom.

In 168 BC Thessaloniki succumbed to Roman rule, after the defeat of Perseus, the King of Macedonia. They, too, erected resplendent monuments and turned the city into the business, cultural and administrative heart of the Balkans. In 58 BC the brilliant Roman orator Cicero was exiled to Thessaloniki; in AD 42, after the Battle of Philippi, Anthony and Octavian declared it the “free city” with all the rights and privileges appertaining thereto. In AD 50, Paul the Apostle visited the city; then, a few centuries later, Galerius Caesar selected Thessaloniki as one of the seats for the Roman Tetrarchy.

Again, eminent buildings, palaces and temples were built: the Roman walls, the Palace Complex, the Octagon, the Hippodrome, the Theater-Stadium, the Roman Forum, the Arch of Galerius, the Rotunda, the Mint and the colonnade later known as “Las Incantadas,” along with the chief Roman highway, the Via Regia. About AD 330, Constantine the Great declared Thessaloniki the second city of the Eastern Byzantine Empire and, until 1430 when it was seized by the Ottomans, exquisite temples and new Byzantine walls were raised.

All the while, the city braved all manner of adversity. It was besieged and overrun by Ostrogoths, Slavs, Saracens, the Normans and Franks; the latter captured the city during the Fourth Crusade and it became the capital of the kingdom of the Lombards, ruled over by an Italian king, Boniface of Monferrat. On its heels, we have the rise of the Zealot movement of 1342-1349, the arrival in Thessaloniki of the first bands of Ashkenazi Jews from Central Europe in 1387, and the Saints Cyril and Methodius christianizing the Slavic people and promulgating the Cyrillic alphabet.

Thessaloniki is at once immutable and volatile, extraordinary and mundane. A city both walled in and open, protean and Byzantine, skittish and bold, Machiavellian and naïve.

Under Ottoman rule, the Muslim districts in the upper part of the city flourished, burgeoning with new holy precincts, mosques, military buildings, the White Tower, the Triangle Tower or the Tower of the Fall, The Fortress of Vardar, the Heptapyrgion (Yedi Koule), the Baths of Paradise and markets such as the Bedestan, etc.

Liberated by the Greek army in 1912, the city was once again beset by adversity: the Balkan Wars, the Great Fire, the Second World War, the German Occupation – during which 96 percent of the Jewish population perished – and the civil war. But this is a city that has withstood 25 centuries; it holds in its hallowed heart the traces of Romans and ancient Macedonians; a thousand years of Byzantium; the wounds made by barbarian spearheads; Frankish and Ottoman houses of worship. From center to periphery it is laden with riches comparable only to those that lie restlessly in wait under the earth. As these treasures surface – which they do, continually – they bear incontrovertible witness to all that the city has lived through; they proclaim its dignity in the face of the most recent wave of barbarity, a sea of concrete and incivility.

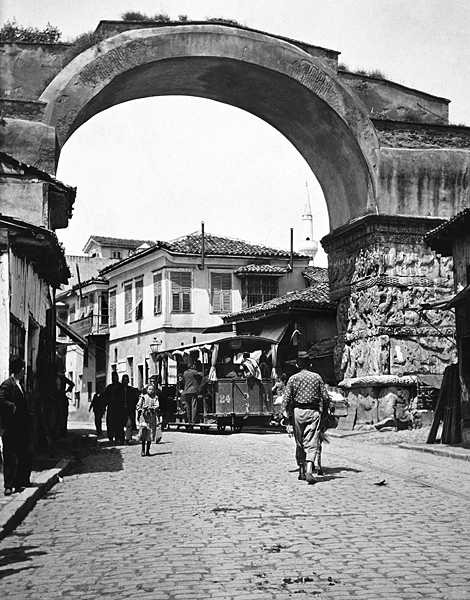

Street cars and pedestrians pass under the Arch of Galerius, 100 years ago.

© Corbis / Smart Magna

Alexander the Great and His Sister, the Mermaid, 1984 oil painting by celebrated artist, playwright and political cartoonist Chrysanthos Mentis Bostantzoglou (pen name “Bost”).

© Mentis Bonstantzoglou / Municipal Art Gallery of Thessaloniki Collection

Thessaloniki is at once immutable and volatile, extraordinary and mundane. It is a city both walled in and open, protean and Byzantine, skittish and bold, Machiavellian and naïve. Multitudinous and manifold, its secret pathways disappear into decades shadowed by notorious murders and burnished by breakthrough innovation. The city is a multitude – multidimensional, multifocal, multipolar; a sacred and profane palimpsest buried deep under a surface frivolity. It is a crossroads marked by perpetual returns; a yawning maw of resignation and pride; a tale both convoluted and cyclical echoing the most ethereal, ghostly, and multifarious of webs, the finest of nets, the thickest of snares.

Thessaloniki is always in the process of becoming: it crumbles and bleeds and then rises up out of the ashes, whole. It is not an easy city to comprehend, but it’s well worth the effort. Those familiar with the city’s literature and architecture will tell you that the simple coffee shop in front of you was once the headquarters of Dagoulas, chief of the security battalions under the German occupation: before that, it was an opium den to the Dervishes and a Byzantine tailor shop; and before that, a Macedonian bath house. When you know this, you cannot help but see things in a new light. For the archaeology of the future, nothing is off limits, yet there is one thing it cannot touch or tarnish: the poet, that “primeval creature,” who spends the night roaming through this occupied yet always free city.

1947: A fish vendor weighs his wares at the harbor.

© Corbis / Smart Magna

Let us not forget that Thessaloniki is defined and determined not only by the city’s own intrinsic value but also by Constantinople’s watchful eye and by the blessings of neighboring Mount Athos; of Pella, the capital of Macedonia; of Vergina and Olympus, the mountain of the Gods. Within an equally small span of the compass, the city cohabits with: Aristotle’s and Potidaea’s Chalcidice, the point of origin for the Peloponnesian Wars; the great Kasta Tomb at Amphipolis and Thucydides’ gold mines of Paggeo; Kastoria with its 200 Byzantine churches. The city of Veria and the island of Thassos. Two hours to the north, we find Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria, and two to the east, Samothrace with its Sanctuary of the Great Gods and the Cabirian Mysteries.

This land ensnares you in its endless labyrinthine stories shaped by hopelessly tangled plots that dissipate only to return in a different form. It presents you with an assortment of facades and mysteries, fiends and cherubs, glory and ignominy, reticence and uplift; rumors and shadows, arias and shrieks, kings and slaves. You see them often, looming wraith-like in the morning mists of the waterfront. Empty, striped uniforms worn by the Jews come and go, floating in the air. Suddenly you hear, in passing, the heavy footsteps of Saint Gregory of Palamas receding around the corner; the faraway strum of Tsitsanis’ chords; hallelujahs, uttered centuries ago, but still vibrant until they slip away into Dimitrios the Besieger’s concealed tunnels, or drift into the hubbub of the fish taverns in Modiano Market. Thessaloniki is many cities in one, inexhaustible. A home to the homeless, a nesting place for every sparrow, a wineskin in the smoke, the open secret that is the smoking-room of the poets.

Aigai’s newly restored Macedonian palace represents...

Major infrastructure projects, a significant urban...

The Thessaloniki-born winemaker welcomes us to...

Where dusk, movement, and memory meet,...