Kyriakos Pittakis and Louis Fauvel shared the same passion for the ancient world: While the former became a pioneer of Greek archaeology, the latter was a French vice consul and, above all, a collector. While Pittakis made painstaking sacrifices in order to record and safeguard Greece’s ancient heritage, Fauvel acquired his favorite ancient pieces through a string of illegal activities.

Almost 200 years have gone by since the days when the two men would exchange thoughts on Athenian antiquities, although their approach in terms of whose property they were differed enormously: The Frenchman supplied European museums with ancient pieces, while the Greek helped establish the first state collections and museums in Athens – Pittakis essentially laid the foundations for the development of the National Archaeological Museum.

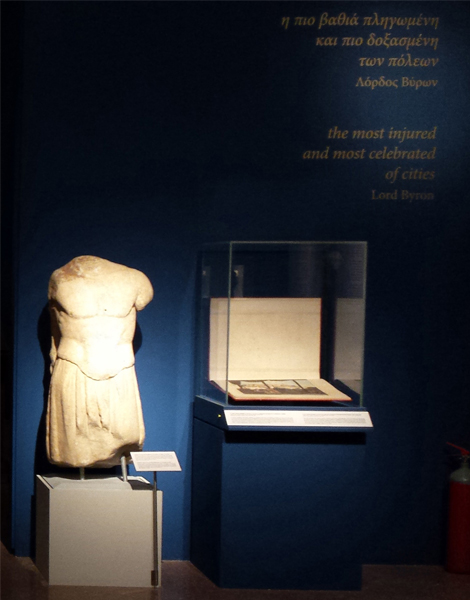

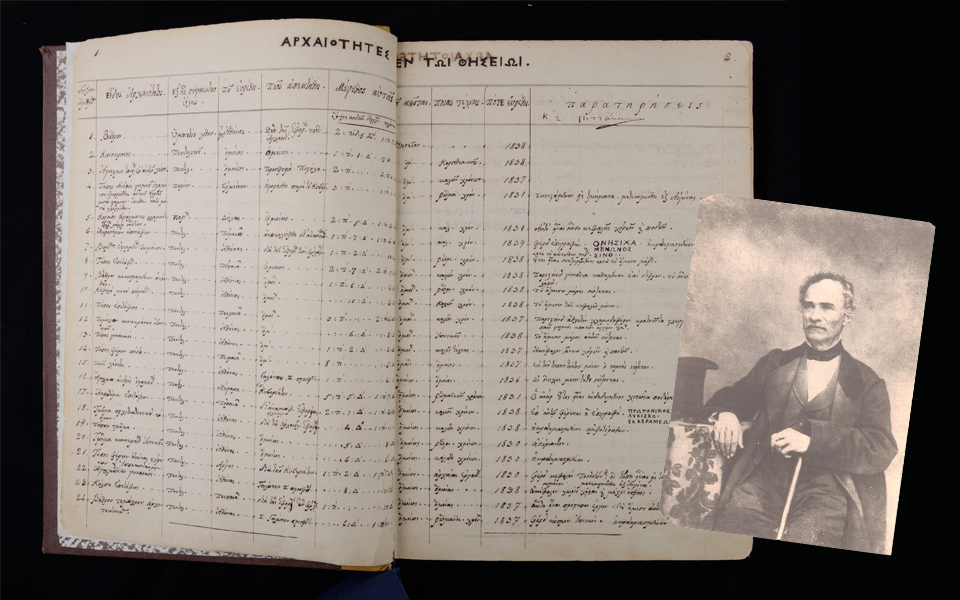

The two men meet again in a National Archaeological Museum exhibition titled “Dream Among Splendid Ruins: Strolling through the Athens of Travelers, 17th-19th Century,” which runs through October 2016. The display presents the two men’s parallel, yet very different, stories. A lithograph by artist Louis Dupre perfectly reflects Fauvel’s arrogance as he poses alongside the Greek antiquities he kept at home. Among them is the torso of a sculpture of an ancient Greek soldier. That same torso is now a part of the exhibition, sparking strong emotion, just like Pittakis’s handwritten inventory detailing antiquities kept at the Temple of Hephaestus in Thiseio, at the Propylaea of the Acropolis and Hadrian’s Library in 1843.

Also on display at the museum, the country’s oldest, are several antiquities rescued by Pittakis.

“Back in the days of the self-taught Greek archaeologist, these antiquities were on display in the Temple of Hephaestus, but by the end of the 19th century they had been transferred to the National Archaeological Museum, when the building was completed,” noted the museum’s director Maria Lagogianni.

According to Lagogianni, at the beginning of the 19th century and up until the beginning of the Greek War of Independence, all travelers reaching Athens would end up visiting the residence of Vice Consul Louis-Francois-Sebastian Fauvel (1753-1838), initially near the Roman Agora and later on at the Ancient Agora.

“After 1780, Fauvel traveled extensively through Greece and around Athens as the envoy of Auguste de Choiseul-Gouffier, French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, in order to collect and record antiquities on his behalf and help him supply royal courts and antiquity-loving Europeans with exceptional ancient pieces,” said Lagogianni.

Following his appointment as vice consul, Fauvel took up permanent residence in Athens in 1803. He now had plenty of time, according to Lagogianni, “to carry out illegal operations involving antiquities across Attica as well as use his rich knowledge of the city’s topography and ancient sites to guide and inform anyone who was interested.”

Besides acting as a consulate, Fauvel’s home became the city’s first private museum, featuring sculptures, figurines, coins, vases and monument casts along with a detailed topographic map of Athens. When the War of Independence broke out in Athens, a bomb explosion caused extensive damage to the vice consul-collector’s home.

“ At the beginning of the 19th century and up until the beginning of the Greek War of Independence, all travelers reaching Athens would end up visiting the residence of Vice Consul Louis-Francois-Sebastian Fauvel (1753-1838), initially near the Roman Agora and later on at the Ancient Agora.”

“The pro-Turkish political stance adopted by the French Consulate forced Fauvel to leave the city in 1822. Initially he moved to Syros and then to Smyrna. From there, he asked for his collection of antiquities to be forwarded to him – he had already taken care of the packaging – but Athens garrison commander Ioannis Gouras and other city officials refused to do so. In 1825, during the second siege of the Acropolis, his house was completely destroyed and all the boxes containing the ancient pieces were crushed under the rubble,” noted Lagogianni. A number of those antiquities were recovered during excavation work in the area of the Ancient Agora in 1935.

Pittakis (1798-1863) was equally passionate about antiquities. He trained next to Fauvel in an effort to learn more about his country’s ancient monuments and soon became a leading advocate in the struggle to protect them. “They say it was his idea to give bullets to the besieged Turks inside the Acropolis so they wouldn’t destroy the columns in order to extract the lead,” said Lagogianni.

Following Greece’s independence, Pittakis was appointed foreman for antiquities in Athens and fought fiercely to put together the first state collections initially housed at the city’s best-preserved monuments: Hadrian’s Library, the Acropolis, the Tower of the Winds and the Temple of Hephaestus. He also edited catalogs and secured antiquities in place to protect them against theft. He tried to stop the illicit trade in antiquities and to prove to Europeans that Greeks were worthy of looking after their ancient heritage.

Originally published in Kathimerini newspaper

“They say it was Pittakis’ idea to give bullets to the besieged Turks inside the Acropolis so they wouldn’t destroy the columns in order to extract the lead,” said Lagogianni.