A Perfect Saronic Weekend: Exploring Aegina’s Ancient Highlights

A compact archaeological guide to the...

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

A brilliant new cultural monument is rising from the lush Macedonian countryside of northern Greece. The newly constructed Polycentric Museum of Aigai, near the town of Veria to the south of Thessaloniki, has already opened its doors, but there is so much more to come… The plan is eventually for the main museum building to serve as an illuminating gateway to three major areas of Aigai, the extraordinary royal capital of ancient Macedonia: the burial cluster of Philip II (with its existing Museum of the Royal Tombs); the palace, with its associated theater; and the tumuli cemetery, with its burial clusters of the Temenid kings and queens. Particularly exciting will be the in-situ partial reconstruction of Philip II’s palace, slated to rise some seven meters above its once-humble ruins and to begin welcoming visitors by the end of 2023.

The fifth and sixth components of the new Polycentric Museum’s complex are a soon-to-be-completed virtual Museum of Alexander the Great and the recently restored 16th-century Church of Aghios Demetrios in the adjacent village of Palatitsia – a three-aisled basilica with magnificent wall paintings. In the narthex, Alexander the Great appears as a Byzantine emperor, with his name inscribed beside his head! The church stands at what was once the easternmost point of Aigai’s necropolis, and most of its building material came from the ruins of Philip’s palace.

We recently had the opportunity to visit Aigai, tour the site’s current exhibitions and accessible areas, and speak with Dr. Angeliki Kottaridi, the director of the Imathia Ephorate of Antiquities and the primary force behind the new museum. This remarkable contribution to Greece’s cultural heritage, spearheaded by Kottaridi, offers its visitors a fascinating experience, bringing them into closer and more extensive contact with ancient Macedonia’s royal figures and daily life than was ever possible before.

Women’s bronze, gold, carnelian accessories, from Iron Age graves: figure-eight and bow-shaped pins, bracelets, spiral rings; 11th-7th c. BC.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Terracotta figures from the Palace: Mother of the Gods, Tyche, Athena, Heracles, Aphrodite, Eros, Dionysus, sacrificial altars & bulls.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

A visit through the galleries of the new Aigai museum is designed to be an incremental journey of discovery as one progresses thematically, moving from the larger Hellenistic world to the Macedonian capital’s palace, with its male banqueting halls and women’s private domestic spaces, and finally into Aigai’s royal necropolis, or “city of the dead.” From the moment you enter the museum’s spacious foyer, you’re treated to a cascade of colorful panoramic images of Alexander the Great’s eastward-stretching empire, projected on giant twin video screens, reminding you of the far-reaching influence and legacy of Aigai.

Through a doorway on the left, a small gallery for temporary exhibitions now presents “The Antidoron of the Oikoumene,” an extensive collection of gold, silver and bronze coins – called “antidoron,” or “return-gifts” – that further illuminate the theme of the “Oikoumene,” the expanded and more inclusive globalized world created by Alexander the Great. Through the coins’ obverse portrait images – tiny, beautifully crafted works of propagandistic art that regularly crossed the palms of ancient people – we come face to face with an array of historical leaders, both Macedonian (or Macedonian-related) and foreign, who, through the centuries, either ruled Macedonia itself or governed its distant territories. Also appearing are Roman and Byzantine emperors, who eventually succeeded the Macedonians as rulers of the known world. In international commerce, the circulation of such coinage was itself a unifying factor, with many of these coin types from the Oikoumene eventually making their way back to the markets of Aigai, where it all began.

Of particular interest in this temporary gallery is a relief-carved marble ceiling coffer depicting Zeus-Ammon – the divine “father” of Alexander the Great – which was unearthed at nearby Veria. This remarkable artifact from the 2nd/3rd c. AD shows that Alexander’s historic legacy was also perpetuated right here at Veria – the new seat of Macedonian authority, albeit now under the control of the Romans.

Visitors trace ancient Macedonia's impact on the Mediterranean world, in the Museum's temporary exhibition gallery.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Back in the main foyer, one cannot help but marvel at the Aigai Museum’s modern design, which combines high ceilings and white walls with reminders of historic architecture – in particular the courtyard (“peristyle”) houses of the Hellenistic era. Colonnaded courtyards were a defining feature of Hellenistic architecture in the broader Oikoumene, as we see, for example, in the houses of Olynthos or Delos. The royal seat at Aigai, according to Dr. Kottaridi, was a center of architectural influence that radiated far out through the dominions of Philip II and Alexander.

At the new museum, two large, semi-roofed courtyards flanked by enormous windows fill the building with natural light and air. These bright spaces hold the first two significant displays of the museum’s permanent exhibition – “The Remembrance of Aigai.” The left courtyard presents a finely executed reconstruction of the upper story of the east façade of the palace. Incorporated into this standing façade and placed individually along the court’s side walls can be seen the surprisingly meager remains of the original structure, reminding visitors of the great efforts and care that have gone into interpreting and resurrecting this 4th c. BC building.

The right-hand courtyard features a variety of marble sculptures, including relief-carved frieze blocks, steles, altars, and other grave markers. Especially significant are the votive statue of Queen Eurydice (wife of Amyntas III, mother of Philip II) and several inscribed bases for dedications that specifically name her as the donor – thus providing irrefutable evidence of the Temenids’ presence at Aigai. Eurydice was a crucial central figure in Macedonian, and indeed Hellenistic, history, as she, a widowed queen, overcame her own personal circumstances in a time of great turmoil to preserve the throne for her sons. “If she had not intervened at the critical moment, we would not have had the Hellenistic Oikoumene,” Kottaridi reminds us.

Aigai Museum Director Angeliki Kottaridi, appreciating Queen Eurydice, mother of Philip II, without whose strong leadership Philip and Alexander would never have come to the Macedonian throne. Her votive statue provides irrefutable evidence of the Temenid dynasty at Aigai.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

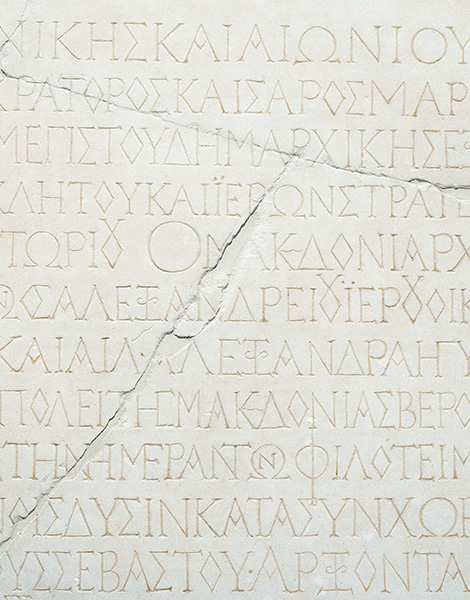

Inscription from Veria mentioning the inauguration of games in honor of Alexander the Great, AD 240, showing Alexander's legacy continued in ancient Macedonia even after Aigai was eclipsed by Veria as the occupying Romans’ new seat of authority.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Nowadays, there is another strong female leader at Aigai, as Kottaridi, backed by her team of specialists and other supporters who have ensured the archaeological, financial and bureaucratic success of the new museum project, pushes ahead to realize a dream that began decades ago. Ever since she was a young archaeologist in the 1980s and ’90s, often working alongside Prof. Manolis Andronikos, the discoverer of Philip II’s tomb (1977), Kottaridi has been a tireless, multi-tasking scientist, dedicating her professional life to the investigation and presentation of Aigai. Even before becoming an ephorate director in 2010, she had drawn up a comprehensive plan for the Polycentric Museum of Aigai; she later went on to oversee the construction and outfitting of its premises (2015-2022). However, as she nears retirement, Kottaridi’s distinctive legacy in Greek archaeology is based not only on her past record but on her current, ongoing endeavors as well. At the top of that list is her determination to restore Aigai to its well-deserved place in Macedonian history.

Aigai, not Pella, Kottaridi tells us, was the political, administrative and cultural center of the Macedonian kingdom at the time of the Temenid dynasty (about 700-310 BC); this was the place where the royals lived and ruled, where Philip II was proclaimed king in 359 BC and assassinated in 336 BC, and where Alexander assumed the throne and subsequently launched his own campaign to the east in 334 BC. Modern historians have traditionally contended that Pella was established by Archelaos I around 400 BC and soon became the new capital of Macedonia. However, no historical evidence exists to support this idea. Pella was unquestionably a large, affluent Hellenistic port, but archaeological and geomorphological studies now show that its palace lies far inland from the once-coastal, now-silted area of the city that Philip II and his son had occasionally frequented. Moreover, the currently visible agora (or central square/marketplace) of Pella lies on top of the necropolis that had previously existed outside the city during the Temenid era. This indicates that Pella expanded outward to include these areas perhaps a century later than previously believed and, according to Kottaridi, was a place more important to the post-Temenid kings of the Antipatrid and Antigonid dynasties.

The royal residence of Archelaos – who decorated his halls with paintings by the preeminent Zeuxes and who played host to famous artists, musicians, poets and writers, including Euripides – was at Aiga, not Pella, Kottaridi concludes. A clear indication of Archelaos’ connection with Aigai (whose name means “the Place of the Goats”) is found on his silver coins, on which are depicted the front half of a goat. Kottaridi adds that the supposed transfer of the Macedonian capital to Pella under Archelaos is a construct of the 20th century that needs to be amended.

Wandering among Aigai's Iron Age "Queens."

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

These fresh ideas are displayed everywhere throughout the new Aigai Museum. Dr. Kottaridi’s words and perspective permeate the visitor’s experience, from the exhibition’s design to its information panels and individual labels. Her reassessment of the historical sources and the roles of Aigai, Pella, and Philip II offers both a watershed moment for Macedonian history and a cautionary tale on making contemporary amendments to ancient sources or not giving them enough credence.

Herodotus’ mention of Pella shows it already existed by at least the 5th c. BC, while Xenophon implies it was larger than Aigai – – indeed, one would expect such a well-placed coastal town to be a large thriving trade center. Demosthenes reports Philip was brought up there, although there is no direct evidence for either his or Alexander’s birthplaces. We do know these two spent time in Pella, where Philip received embassies, such as that of the Athenians in 346 BC, described by Demosthenes and Aeschines. In the end, it appears Aigai and Pella were closely linked, with Pella being a larger, more accessible port town, in contrast to Aigai, which remained the Temenids’ ancestral royal seat and residential enclave, as well as home to their entourage of fellow nobles and companions.

Bronze Gorgon decorative applique for a bronze vessel, from a royal grave, late 4th/early 3rd c. BC.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

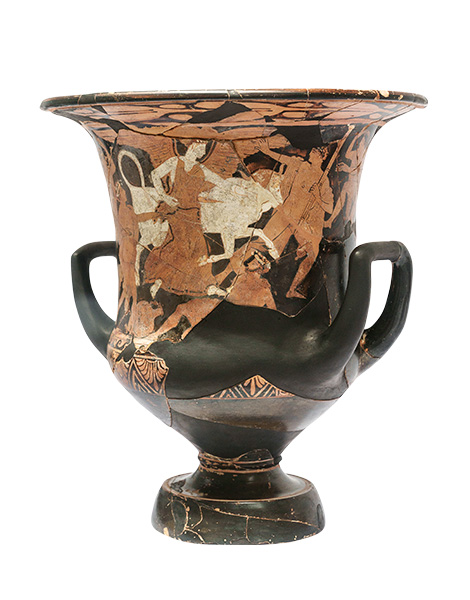

An Attic calyx krater with sacrificial scene, 4th c. BC.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

In a particularly intriguing remark, Kottaridi says the new Polycentric Museum “has been created not for archaeologists, but for all people interested in learning Macedonian history and having contact with the past.” In this vein, the objects are arranged in a strikingly artistic manner, without many individual labels or the usual dizzying array of artifact numbers. Important information is conveyed through numerous narrative plaques. Most of the museum’s finds come from Aigai’s excavated palace and from thousands of graves. Nevertheless, they appear in thematic groupings to illustrate ordinary life, construction, destruction, warfare, men’s banqueting rituals, women’s private and domestic activities, and the luxurious funerary practices of Iron Age noble ladies and Temenid kings and queens.

There are many facts to be gleaned from the information panels. Still, the most remarkable immediate impression is made by the innovative artistry of the artifact exhibits – arranged either in distinctly patterned “tableaux” or in reconstructions of their original burial positions – and by the often poetic tone of their labels; in the first gallery after the courtyards, visitors read that five large showcases on the wall represent “a ‘book’ with five pages or scrolls,” displaying artifacts which, “liberated from the layers of [the palace’s] destruction, are raised to the firmament of memory, becom[ing] words and sentences that reveal the identity of the city, the fingerprints and thoughts of the inhabitants…” Opposite stands a long case of bronze “sarissa” lances, smaller weapons, helmets, and scrapers (or strigils), which accompanied Macedonian warriors “in life and death [and now] march with shouts of victory to hail the long-yearned return into the remembrance of their descendants.”

Heads of korai (maidens) and daemons (spirits), early 5th c. BC.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Among the artifacts displayed in the museum’s middle galleries are roof tiles still bearing the impressions of the fingers that made them or the footprints of Aigai’s humbler animal residents, including goats, chickens, cats and dogs. Another tile is stamped “AMYNTOU,” affirming the existence of a prominent shrine probably dedicated to Amyntas III, Philip’s father. Fragmentary tiles marked with goats’ heads also confirm Aigai’s identity. Further displays present bronze keys, ornaments, equestrian equipment, ceramic cups and plates, lamps, writing implements, household tools, and terracotta figurines of Athena, Dionysus, and Heracles, the Temenids’ mythical ancestor. More recent hammerheads and wedges from the palace’s ruins point to the “quarrying” of the historic site by early modern villagers seeking building materials for their homes and churches.

After passing through a space meant to call to mind a customary “andron” (male dining hall) – filled with jugs, kraters, drinking cups, and other symposia vessels of the Geometric, Archaic and Classical eras – the visitors comes to some of the Museum’s most unexpected and delightful displays. First, a small gallery evoking females’ traditionally secluded residential quarters holds two more “tableaux” cases with creatively arranged and fascinating selections of women’s ornaments, jewelry, miniature perfume dispensers, and other cherished personal possessions. Even the more commonplace loom weights are exhibited inventively, suspended together as if for use on an actual loom.

An “Illyrian” type helmet common among Macedonian troops, likely dating to the 6th c. BC.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

A roof tile fragment stamped with a goat’s head, identifying it with Aigai (“The Goats”).

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

A large hall presents the “Remembrance” exhibition’s stirring culmination, with elite and royal funerary goods from the Aigai necropolis and its burial tumuli of “The Temenids” and “The Queens.” Here, Kottaridi and her team colorfully envision visitors “experiencing” a “nekyia” – an ancient rite in which spirits of the deceased were called up and questioned. One panel reads: “The objects – so full of meaning – truly shine as ‘beings’…, ready to share their truth in a[n]… environment that both respects and exalts them.” Thus, the treasures of Aigai are meant to “speak” to us, and they almost seem to do so. The abundance and the diversity of the ancient material on display are particularly impressive. Despite extensive looting and repeated sackings of Aigai (by Pyrrhus’ troops in 273 BC and the Romans in 148 BC), much has survived.

Magnificent Attic polychromatic white-ground lekythoi by known painters – along with black-figure, red-figure, and black-glazed banqueting vases in the previous room – attest to Athenian trade and influence in the 6th-4th c. BC. The Temenid kings are represented by objects from their funeral pyres and tombs and through written descriptions on an information panel. The “Queens” – in fact, pre-Temenid “noblewomen” (10th-8th c. BC) and the so-called “Lady of Aigai” (495 BC) identified as the Lydian wife of Amyntas I – have had their personal funerary adornments and other gifts arranged on or in front of standing, translucent, human-like forms, imparting the striking impression that these ladies have ethereally reappeared before us.

Six of the Iron Age figures are accompanied by tall, originally wooden rods – apparently scepters – topped with triple bronze double-axes. These noblewomen remind us that this site, even before it was Aigai, was already a regional center inhabited by well-to-do elites. The “Lady of Aigai’s” gold, silver, bronze and ivory grave goods are wondrous, and include a gilt-edged veil, pins, jewelry, a scepter, a distaff, a spindle, a phiale for offerings, a hydria (water jar), libation bowls, and golden-soled slippers.

As artistic, fresh and informative as the new Aigai Museum clearly is, it’s also still a work in progress. To fully understand the rich, innovative displays that the new Aigai Museum offers, visitors need to carefully read all the narrative panels, which are lengthy and dense (often over 2000 words of text). Eventually, they’ll be able to scan QR codes and take these texts with them to peruse later, or perhaps access internet resources on their mobile phones, but at the moment, neither the QR system nor reliable internet or mobile phone service are available in the main museum building. The café and bookshop, too, remain as yet unfinished.

Coming “face to face” with Temenid royals buried at Aigai.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Despite any temporary drawbacks, the Polycentric Museum of Aigai represents a gigantic, inspiring step forward in understanding the cultural heritage of ancient Macedonia. Establishing a museum complex with some 7,000 sq. m of new exhibition space and resurrecting the monumental architecture of Aigai’s royal palace have been enormous tasks, and the digital Museum of Alexander the Great promises even greater historical riches. Most importantly, material evidence for an evolving interpretation of the roles of Aigai and of Philip II himself is now, more than ever, on display. Given the splendor of the royal graves and the architectural, social, and political significance of Philip’s inherited Temenid seat at Aigai, it seems little wonder that Kottaridi has drawn parallels between the golden ages of Macedonia and Periclean Athens.

The Athenians may have focused their energies on democracy and democratic institutions, and monarchy and individual power may have been the driving force in Macedonia, but Kottaridi argues that Philip was an enlightened, ambitious, and far-reaching king, surrounded by some of the leading creative minds of the day. Although she herself has previously conceded that her more benevolent view of Philip could upset scholarly traditionalists, it’s doubtless that the lay public and archaeological specialists alike will find much to marvel at here, in the Macedonian heartland, where leading artists and thinkers of the day gathered, where crucial policies were decided, where a scion was likely born and raised, and from where an eastward military mission was launched that would forever change the world. Alexander the Great’s inclusive approach to diverse cultures and his “globalized” Hellenistic world community – the Oikoumene – holds lessons on tolerance and on our shared human experience from which we can all still benefit today.

Visitors enter the new Polycentric Museum of Aigai, at Vergina, in the heartland of ancient Macedonia.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Polycentric Museum of Aigai

Archaeological site of Aigai, Vergina, Imathia, Tel: (+30) 23310.925.80.

Open

From November until end March 2024, Mon, Wed-Sun 09:00-17:00, Tue closed.

From April to end October Mon, Wed-Sun 08:00-20:00, Tue 12:00-20:00.

A compact archaeological guide to the...

Whether drizzled on lentils, stirred into...

Beneath the busy streets of modern...

Lost to earthquakes, swallowed by the...