Archaeological Museum of Crete

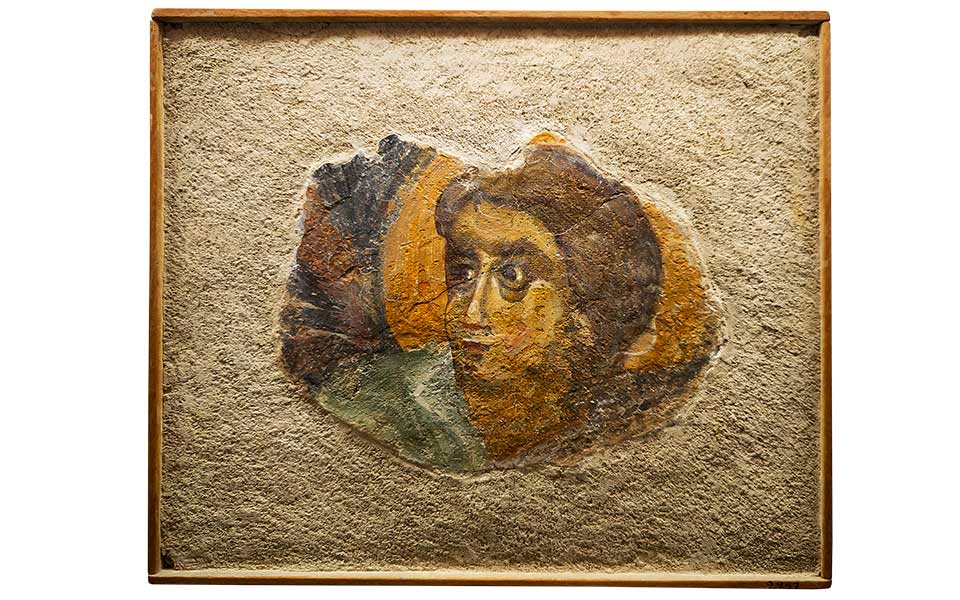

The preeminent museum dedicated to Minoan civilization, the Archaeological Museum of Crete is one of the most important archaeological museums, not only in Greece but also in Europe. The building was constructed on the site of the Venetian Monastery of Saint Francis, which was destroyed in the earthquake of 1856. Following its recent renovation, it features 27 rooms with exhibits from the Neolithic era to Roman times (6th millennium BC – 3rd century AD), with the Minoan collection given pride of place.

Here, among other things, you can see the Phaistos Disc, the famous golden pendant in the shape of two bees from Malia, and frescoes from the Knossos palace, including Prince of the Lilies, the Blue Bird, Dolphins, and the Rhyton Bearers. We then move on to exhibits from the period following the collapse of the Minoan civilization, which was incorrectly labeled as “dark,” despite the fact that findings from this era demonstrate that Crete was a creative and outward-looking society that eventually developed a new way of life through its arts, trade, and economy. On the ground floor, there is a separate section with sculptures dating from the 7th century BC to the 3rd century AD.

© Vassilis Makris

© Vassilis Makris

© Vassilis Makris

“The Ring of Minos”

The Ring of Minos’ (1450-1400 B.C.) archaeological and aesthetic value stems from the insight it provides into Minoan religious iconography. It is a signet ring made of solid gold, which weighs 32 grams and measures 3.55 x 2.35 cm. These characteristics suggest that the owner of the ring was of high administrative rank. It is regarded as one of the most representative examples of Minoan art, which was characterized by abstraction (reduction to specific symbols without elaboration), a code (visual writing understood by all), and narrative (through myths created by the people).

It depicts three levels with scenes of theophany (gods appearing to humans), representing Minoan sovereignty over heaven, earth, and sea. It is an extremely rare narrative in that it depicts the works and days of a deity, rather than simply their worship. The representation shows the goddess descending from the sky, sitting on an altar, and observing the tree worship performed in her honor before finally rowing away in a boat transporting a temple (according to another interpretation, the vessel itself is a temple).

Equally fascinating is the ring’s journey through modern times until it was eventually brought to the museum. In 1926, Michail Papadakis found it by chance in a vineyard near Knossos. Because it was made of precious material, his family kept the ring, but two years later they sold it to local priest Nikos Polakis, who showed it to Spyros Marinatos in 1930. Marinatos questioned its authenticity because no other artifacts of the same style had yet been discovered. Archaeologist Nikos Platonas disagreed, so he photographed it and kept a copy in his archives. When Sir Arthur Evans, who was then residing at Villa Ariadne, learned of it, he made the decision to excavate the site, where he found a series of large royal tombs along with a burial deposit consisting of jewelry. He continued the excavation and unearthed the tomb-sanctuary, a rare architectural structure with Egyptian architectural characteristics, believed to be a royal burial site. Meanwhile, although the trail of the ring was lost, Evans had already given it the name “The Ring of Minos,” based on the myth of Theseus and King Minos, who threw his ring into the sea and asked Theseus to prove that he was the son of Poseidon by retrieving it. Finally, in 2002, Polakis’s grandson discovered the ring hidden in his grandfather’s chimney and delivered it to the Archaeological Museum, where it is now on display after being authenticated.

See also: On the first floor, look for the inscription that reveals that the Cretans developed their own alphabet based on the Phoenician one in the 8th-7th centuries BC.

© Vassilis Makris

Historical Museum of Crete

Housed in the A. & M. Kalokairinos House, the museum was established in 1953 with the aim of serving as a thematic continuation of the Archaeological Museum. Its 23 rooms contain ceramics and sculptures from the early Christian years (4th-5th century AD) to the Ottoman rule, coins, and exhibits from the two periods of Byzantine rule (330-826, 961-1204) and the Arab Emirate (826-961), as well as items from the post-Byzantine period.

These exhibits illustrate, on the one hand, the coexistence of the local Orthodox population with the Venetians and, on the other hand, the social changes that took place after the Ottoman conquest. Here you will also see the 65 portable icons from the Zacharias Portalakis Collection (15th-20th century), which were donated by the collector.

Info

27 Sofokli Venizelou and 7 Lysimachou Kalokairinou

Tel. (+30) 2810.283.219

© Vassilis Makris

© Model representing Candia (Irakleio) during the Venetian period.

© Vassilis Makris

Model representing Candia (Irakleio)

The 15-square-meter model of Chandax (Irakleio) at its peak in the mid-17th century is reason enough to visit the museum. It is a reconstruction based on the cartography of Werdmuller, Coronelli, and Klontza, focusing on the 450 years of Venetian rule, which has left traces that are visible in the city to this day. It primarily features Venetian buildings, but the exhibits also include Ottoman works created after the 1856 earthquake. A characteristic example is the iconic Church of the Savior (Sotiros), which was converted into the Valide (Falté) Mosque and then housed a Gymnasium, before finally being demolished in 1970. Today, it is the site of Kornarou Square, which includes the Ibrahim Aga fountain and the Bebo spring, examples of the trend of reusing materials that developed in Irakleio due to a lack of resources.

See also: The museum hosts the only two works by Domenikos Theotokopoulos (El Greco, 1541-1614) that are on display in Crete: “The Baptism of Christ” (1567) and “View of Mount Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine” (1570). The exceptional reconstruction of Nikos Kazantzakis’s study from his home in Antibes, France, is also on display. In a letter to the Society of Cretan Historical Studies in 1957, Kazantzakis wrote, “I will give away what I hold most precious – my entire library, manuscripts, and personal belongings that I loved and used. A perfect replica of my desk at the Great Castle. This will help preserve my cell, where a Cretan spiritual worker toiled for many years.”

© Vassilis Makris

Vikelaia Municipal Library

It was named after the author and man of letters Dimitrios Vikelas (1835-1908), who bequeathed his personal library to the Municipality of Irakleio. Its shelves are estimated to hold approximately 180,000 volumes. The Archives Department includes original documents or copies that provide valuable testimonies about the city’s history. Among the most important are the archives of the Kingdom of Crete (acquired in microfilm in 1992), which the Venetians took with them in 1668 after the city was surrendered to the Ottomans, the records of the notary of Chandax (deeds, labor contracts, etc.), and the Archives of the Municipality (1858-1900). The Vikelaia Library also has a reading room and a digitized audiovisual archive accessible to the public and produces a significant number of publications.

© Vassilis Makris

© Vassilis Makris

© Vassilis Makris

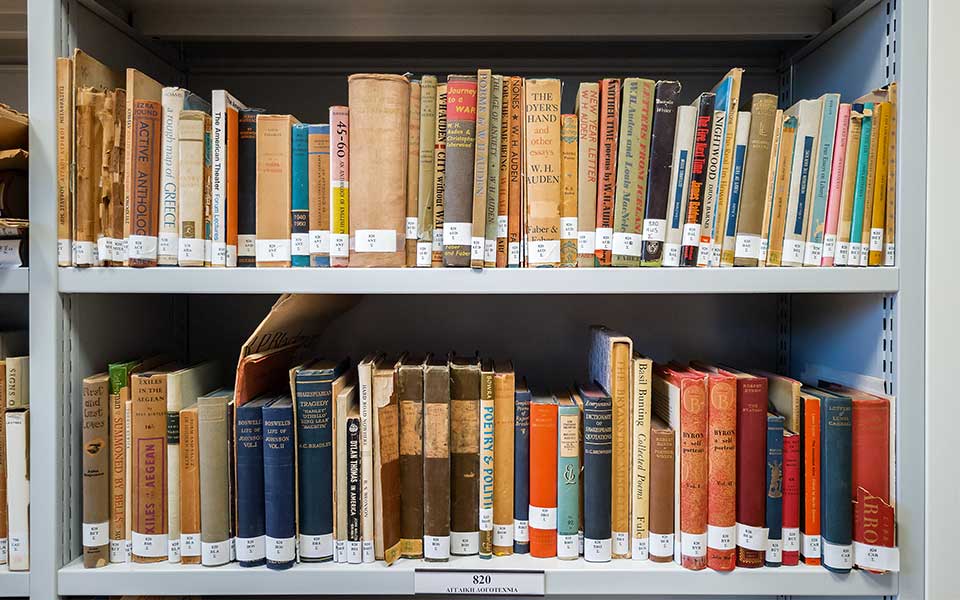

The archive of Giorgos and Maro Seferis

The Vikelaia Library now houses the archive of Giorgos and Maro Seferis in its entirety, following a donation from the poet’s stepdaughter, Anna Londou, who passed away in 2022. After the poet’s death, Maro Seferis donated most of it, a total of 4,733 titles, keeping only 887 as personal mementos. Now complete, the collection includes works of modern Greek, French, and English literature, contemporary philosophy, as well as law, economics, religion, and other subjects.

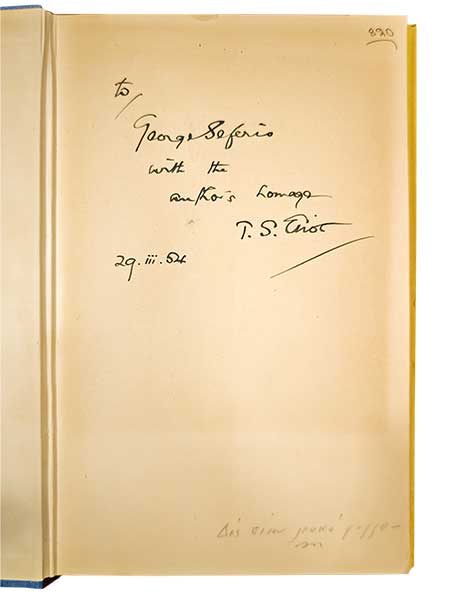

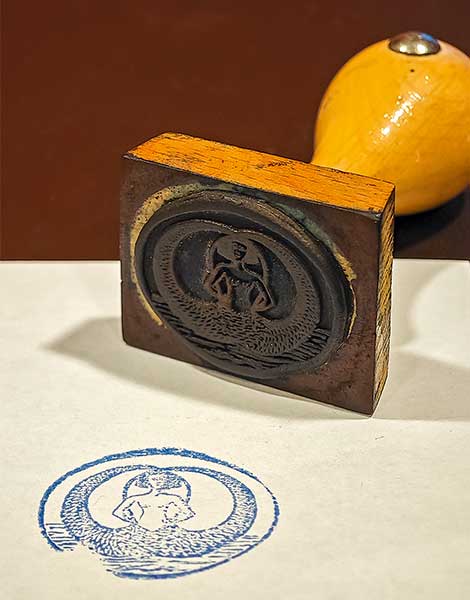

As the dedications reveal, most of the books were given to the poet by their authors, including M. Karagatsis, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and Angelos Sikelianos. 2,000 volumes bear a serial number based on the handwritten catalog prepared by Seferis himself, while the majority bear an ex libris featuring a mermaid or his monogram in a rectangular frame.

See also: Since May 2018, the Vikelaia Library has been operating the Post-Incunabula Conservation Laboratory, which preserves books that were printed in Europe from 1500 to 1800 or before 1500. Conservator Vasilis Panagakis patiently cleans and restores them before storing them in acid-free boxes. The oldest post-incunabulum to be found at Vikelaia is the 9 Comedies of Aristophanes (1498), whose restoration took about seven months.

© Vassilis Makris

Municipal Art Gallery

The collection consists of approximately 1,200 works by significant artists such as Fanourakis, Markogiannakis, Tsarouchis, Vasiliou, Fasianos, Orfanos, and others, acquired through purchases and donations. The Municipal Art Gallery in Irakleio does not have a permanent building to house its collection. However, since 2018, there has been an ongoing project to gather, study, document, record, archive, and categorize all the works in the collection, under the supervision of Marianna Gialiti, curator of the gallery. Additionally, the gallery created the website heraklionartgallery.gr to showcase the collection. The works are exhibited on a rotating basis almost year-round in the Basilica of Aghios Markos, in the historical center of the city. Temporary exhibitions of works by other artists are also held in the same space.

© Vassilis Makris

Perdikes Triptych, Thomas Fanourakis

Few artists left as lasting an impression on the art scene of Irakleio from the interwar period onwards as Thomas Fanourakis (1915-1993). A graduate of the Athens School of Fine Arts, Fanourakis worked at the Irakleio Archaeological Museum, producing technical drawings of archaeological findings. At the same time, he designed costumes and sets for theatrical performances. The Municipal Art Gallery logo, an impressively large triptych on display in the Vikelaia Library’s bookstore, is inspired by his work “Perdikes” (1984). “Charismatic, severe, uncompromising, and with a great sense of humor, he was a master of color. He knew by heart what amounts to mix to get the shade he wanted,” says Aristea Plevri, Deputy Mayor of Culture. Fanourakis’s works are regularly exhibited at the Basilica of Aghios Markos as part of the temporary exhibition program of the Municipal Art Gallery.

See also: Every Friday for the past 11 years, a work from the collection is posted on the gallery’s website, along with information about the artist.

© Vassilis Makris

Natural History Museum of Crete Exhibition

It is part of the School of Natural Sciences of the University of Crete and is housed in the listed building of the Old Electricity Company of Irakleio. In addition to the museum’s main exhibition space, it houses research areas that include laboratories for the study of new finds. Its aim is to develop collections from the broader Eastern Mediterranean region and to study its biodiversity and geodiversity. Work is currently being done to expand its facilities by 2,000 square meters.

“We designed the museum’s exhibition so that visitors could appreciate the enormous environmental diversity in our region, which is at the crossroads of three continents. Through dioramas, visitors take a journey through coastal ecosystems (altitude 0-500 m), wetlands, deserts (altitude 500-700 m), and alpine ecosystems (700-1,000 m and higher),” explains Nikos Poulakakis, director of the museum.

© Vassilis Makris

© Vassilis Makris

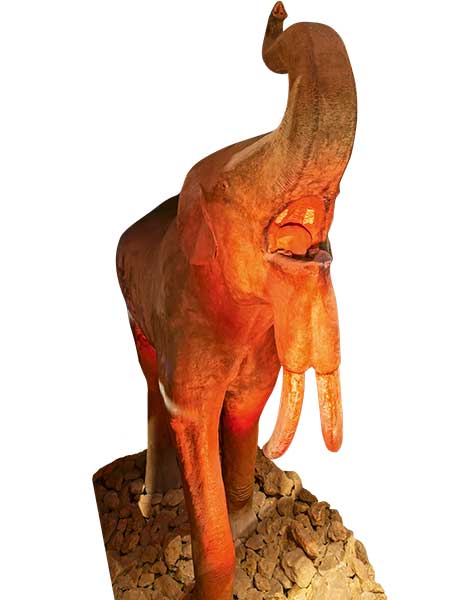

The Deinotherium

The Deinotherium (Deinotherium giganteum), the third-largest mammal in the world, lived in Crete seven million years ago. It measured 4.5 meters in height and 6.5 meters in length and its skeleton is expected to be displayed at the entrance of the museum, which is currently undergoing renovation. This is the most important paleontological find on the island, so a reconstruction of the Deinotherium and some of its bones are housed in a display case in the Paleontology Hall until then. Nearly 60% of the skeleton of this incredibly rare specimen was recovered when it was discovered in an olive grove close to Aghia Fotia in 2002.

See also: Enceladus, an earthquake simulator that replicates a classroom environment where you can experience the effects of an earthquake, and “Erevnotopos,” a space with miniature simulations of Mediterranean ecosystems that has been specifically designed for children and is equipped with interactive games.

© Vassilis Makris

Kostas Kotsanas Museum of Ancient Greek Technology

Since 2019, the Kostas Kotsanas Museum of Ancient Greek Technology has been shedding light on a lesser-known aspect of ancient Greek culture: technology. Housed in the Venetian Ittar Building, it features 90 replicas of various inventions (including Aeneas’ hydraulic telegraph from the 4th century BC, the Antikythera Mechanism, Ctesibius’ Hydraulic Clock from the 3rd century BC, and the first keyboard musical instrument – a precursor to the ecclesiastical organ – among others). These exhibits are accompanied by detailed texts and experiential demonstrations, allowing visitors to learn more about their function.

© Vassilis Makris

© Vassilis Makris

Replica of the lifting tripod

The lifting tripod (6th century BC) is the first vertical lifting crane of antiquity associated with Crete. It resembles a tripod, and the load was lifted from the top by means of pulleys and a rotating shaft. Prior to the development of this technology, the construction of megalithic structures required a large group of people to work together to move heavy things horizontally on an inclined plane. These new machines, combined with various types of winches and wheeled vehicles, gradually led to the miracles of Greek construction that date from the 5th and 6th centuries BC. Even today, lifting technology is still improving on the systems developed by ancient engineers.

See also: The Therapne of Philon (3rd century BC), the first robot in human history, which was “programmed” to serve neat or watered wine to guests according to their preferences.