Visitors to Crete are well advised to spend at least half a day exploring the majestic palace of Knossos, located on the outskirts of the city of Iraklion, the island’s capital. Associated with the story of Theseus and the minotaur, one of the best-known tales from Greek mythology, even those with a perfunctory interest in archaeology are awe-struck by the sheer scale and monumentality of the site.

For visitors who are keen to dive deeper into Crete’s Minoan past, another palatial albeit lesser-known site, Archanes, located some 15km to the southeast, is currently making waves in the world of Aegean archaeology.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

A Summer Palace for Kings?

Pioneering British archaeologist, Sir Arthur Evans, famous for his excavations at Knossos, first carried out exploratory surveys in the area of Archanes in the early 20th century. His initial findings led him to speculate that the site may have served as a summer residence for the kings and elites of nearby Knossos, but it was only when systematic excavations by the Greek Archaeological Society began in the mid-1960s, that the true extent of the site was fully realised.

Project directors, husband-and-wife team Yannis Sakellarakis (1936-2010) and Efi Sapouna-Sakellarakis, unearthed the first definitive evidence of the lavish Minoan-era palace, the scale of which rivalled the size of Knossos. Discounting Evans’ earlier ideas about it being a summer palace, the Sakellarakis’ believed Archanes was a powerful palatial center in its own right.

“It’s too close to Knossos for that to be true,” Efi Sapouna-Sakellarakis explained, in a recent interview with Kathimerini. “Surely it was given to some scion of the Knossos dynasty, who resided there and apparently controlled the nearby peak sanctuary on Juktas. That it was a very important palace is also proven by the equally important cemetery on the neighboring Fourni hill, which yielded five vaulted tombs, with various valuable objects,” she added.

From its strategic location on the northern edge of the Messara Plain of central Crete, the palace was able to exploit the rich and fertile land for crops, olive trees and vineyards, aqueducts for a steady supply of fresh water, and control access to the nearby religious sites at Anemospilia, Korifi, and the peak sanctuary on Mount Juktas.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

Rich Findings

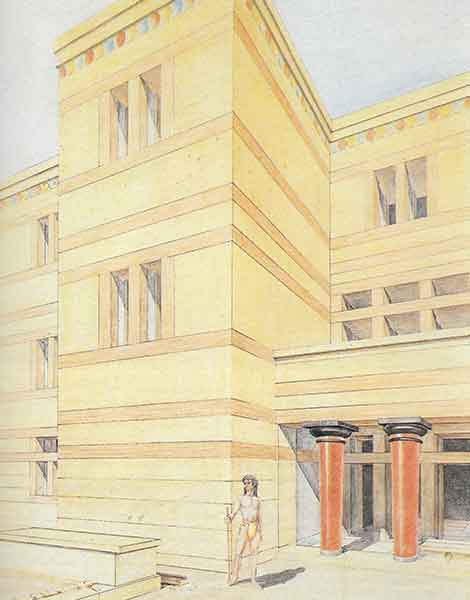

Early excavations at Archanes revealed a palace that shares all the same features as Knossos and Phaistos, another major Minoan site, located on the central south coast. These included a pillared propylon (monumental entranceway), three-storey buildings, elaborate wall frescoes, and blue marble flooring. Like Knossos, the labyrinthine layout of the palace, with its multiple courtyards and open spaces, was designed to accommodate various functions: administrative, ceremonial, and residential.

Excavating in the basements of modern houses, built over the ruins of the palace, the Sakellarakis’ established it was first built around 1900 BC, during the Old Palatial period, a time when Minoan Crete was reaching its cultural zenith. The archaeologists unearthed lavishly decorated limestone buildings, with wall frescoes depicting floral and marine motifs and female figures, as well as floors made of colored pebbles, carved alters, and a multitude of portable artifacts, including gold and ivory figurines, embossed stone lamps, painted ceramics, seals, and clay tablets bearing the, as yet undeciphered, Linear A script.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

Excavations have continued, on and off, since the 1960s, in various areas of the site. The massive palatial complex, estimated to be 18,000 square meters in surface area, lies underneath the modern town of Archanes, in a suburb called “tourkogitonia” (the Turkish neighborhood).

In the 1999/2000 season, it was discovered that the entire northern section of the palace, rooms 30-33, had been destroyed by fire, as evidenced by a thick layer of ash and burnt wood. Amid this layer were 20 large storage jars, used for wine and oil, as well as the preserved remains of textiles, an Egyptian scarab, and smaller ceramic vessels used for perfume.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

A “Shiny” Palace

The most recent excavations, which took place earlier this year, made a number of startling discoveries, adding crucial information about the various construction techniques and materials used in the building of the Palace.

Under the direction of Efi Sapouna-Sakellaraki (her husband, Yiannis, died in 2010), excavations took place in the northernmost part of the site, focusing on the ground floor and first floor, and the area were the aforementioned fire started. In this particular layer, archaeologists unearthed a number of fragments of elaborate stone vessels, including one of mountain crystal, one of grey leucolith, and one of incised steatite, as well as fragments of obsidian, a black volcanic glass-like rock. It is believed that this particular area of the palace served as a religious sanctuary.

One of the most spectacular findings this year was the discovery of the use of gypsum plaster (“stucco”), used to coat the walls of the building. This decorative technique was also used at Knossos and Phaistos. Applied wet, gypsum drys to form a dense solid, textured with tightly-packed quartz crystals. At Archanes, it was applied on pilasters (large columns) and monumental doors, creating the impression of a “shining” building, fit for the Minoan elite.

“Gypsum is a valuable material, because it is difficult to find and use, but mainly because it gives all this shine,” says Sapouna-Sakellarakis.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

Another striking discovery was the presence of elaborate pebble floors and a mosaic of small slates. Finely-plastered walls were also unearthed, preserved to a height of two meters. Fragments of fine mortars, discovered nearby, indicate that the walls may bear frescoes.

Like many Minoan palaces, the Palace of Archanes suffered further destruction during the Late Bronze Age, around 1450 BC, likely due to a catastrophic earthquake. The site was reoccupied during the subsequent Mycenaean era, and experienced a new period of prosperity.

Today, the site has been partially reconstructed and is open to the public. The Hellenic Ministry of Culture recently announced plans to establish a new museum at the site, to house its many treasures. In the meantime, excavations will continue to unearth more secrets.

“The palace of Archanas is so well constructed that it can only be compared to Knossos. I don’t know what else this great space will reveal. Every excavation gives us something new, which surprises us,” Sapouna-Sakellarakis concludes.

With information from kathimerini.gr.