Perched majestically at the southernmost tip of the Attica Peninsula, 69km southeast of Athens, the Temple of Poseidon at Cape Sounion stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of the Golden Age of Athens.

Built in the mid-5th century BC, at a time when Athens was the most powerful city-state in the Greek world, the temple was dedicated to the Olympian god of the sea, emphasizing the symbolic connection between the city and its reliance on naval power.

The main temple seen today is made of coarse-grained marble, quarried from the nearby Agrileza Valley, and commands spectacular views of the surrounding Saronic Gulf. Coupled with its proximity to Athens, at the end of the coastal road that runs south along the Athenian Riviera, it is easy to see why it is such a popular draw for visitors, especially at sunset.

But beyond the breathtaking views, why is the Temple of Poseidon at Sounion such an important site? And what does its construction tell us about the rise of Athens as the supreme naval power in the ancient Greek world?

© Public domain

© Public domain

The Rise of Athenian Sea Power

Sounion’s location made it a strategically important site for the Athenians, not only serving as a religious sanctuary, but as a border post and, latterly, a hilltop fortress, guarding against seaborne threats coming from the south and the east. The fortress included a small naval base, featuring a rock-carved ramp for the launching of ships.

Surrounded on three sides by the sea, the site was sacred to both Poseidon and the goddess Athena, and earlier temples were erected to both deities sometime in the 6th century BC. These were later destroyed by the invading Persians in 480 BC.

It was during the early stages of the Greco-Persian Wars (499-449 BC) that Athens first rose to prominence as a major naval power. Following the discovery of a rich seam of silver at the nearby mines of Laurium, the Athenian statesman and general, Themistocles, an advocate for the strategic importance of naval power, argued that the city’s new found wealth should be used to build a powerful fleet. In 483 BC, he convinced the Athenian Assembly to invest in the construction of 200 triremes, swift and highly maneuverable oared warships, to be crewed by “thetes,” men from the lower classes of Athenian society (namely, those who could not afford to buy the armor or weapons required to serve in the ranks of the army). Despite fierce opposition from his political rival, Aristides, Themistocles’ arguments proved persuasive, and a smaller fleet of 100 triremes was commissioned.

© Public domain

Themistocles’ vision ultimately saved Athens – and, by extension, the Western world – when Persia, under king Xerxes, mounted an invasion of mainland Greece in the summer of 480 BC. At the Battle of Salamis, the combined Greek fleet, led by Themistocles, scored a decisive victory over Xerxes’ navy, effectively ending Persian ambitions to seize control of the Aegean.

In the years that followed, Athens reinforced its navy and established the Delian League, uniting the naval fleets of the Aegean islands and the Greek city-states of western Asia Minor (Ionia) under Athenian leadership – the first step in the creation of its own “empire of the sea” (thalassocracy).

© Public domain

A Navigational Marker

The Temple of Poseidon at Sounion was constructed from 444 to 440 BC, over the ruins of the earlier, destroyed temple. It was built during the ascendancy of the Athenian statesman, Pericles, a period that is often referred to as the “Golden Age” of Athens. At this time, an ambitious building program was underway on the Acropolis in Athens, resulting in one of the most spectacular examples of Classical Greek architecture: the Parthenon.

The placement of the Temple, on a 60m-high cliff, was both religious and strategic. The Cape of Sounion commands unbroken views of the sea lanes approaching Attica from the south and the east. As such, the Temple served as a guard station, enabling the on-site garrison to monitor mercantile ships to and from the Athenian port of Piraeus, and keep a lookout for any potential incoming enemy attacks. Moreover, the Temple, which is clearly visible from as far away as the island of Aegina, served as a landmark for sailors rounding the Cape and navigating the treacherous coastal waters.

© Public domain

© Public domain

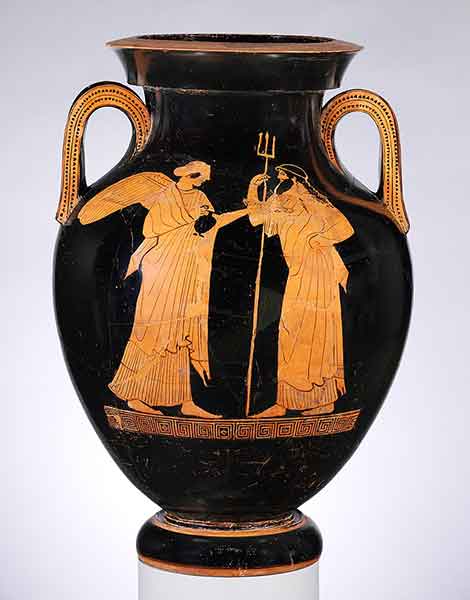

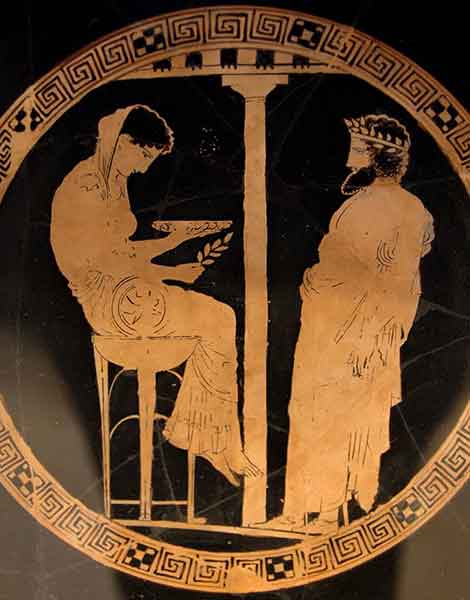

Aside from its strategic location as a border post, the Temple’s dedication to Poseidon held a deep cultural and religious significance for the Athenians. Poseidon was considered second only to his brother, Zeus, in the Olympian pantheon. The sea god’s implacable wrath, which manifested in the form of storms, was greatly feared by all mariners. His favor, therefore, was sought by the Athenian city-state, which relied on the sea for trade, prosperity, and defense. It was not only a place of religious worship but also a site for offerings, prayers, and rituals, emphasizing the divine connection between Athens and the sea.

© Public domain

A Masterpiece of Doric Architecture

Characterized by its simplicity and harmonious proportions, the Temple is a quintessential example of Doric architecture. Perched on a three-step platform (“stylobate”), the building originally consisted of six columns on the short sides, and 13 on the long sides. This typical “hexastyle” design is broadly similar to the contemporary (and better preserved) Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, which may have been designed by the same architect. Of the 34 original columns at Sounion, only 15 remain standing today.

The Temple originally had a gabled roof made of wooden beams and covered with terracotta roof tiles. While the roof and most of the temple’s interior elements have not survived, the triangular pediments at each end and its continuous frieze that ran along all four sides, the space above the columns (the architrave), contained sculptural decoration made of marble from Paros. The scenes depicted the labors of the divine hero, Theseus, founder of Athens, and the battles of the gods with the Centaurs and Giants. The surviving sculptures are showcased at the Lavrio Museum.

© Public domain

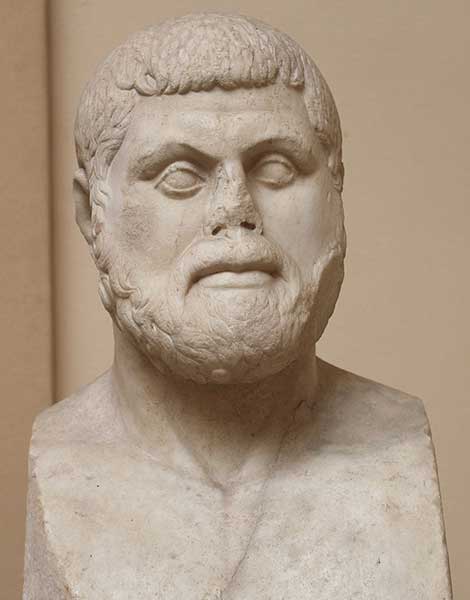

At the centre of the colonnade was the inner sanctum (“naos”), a windowless rectangular room that housed a colossal, ceiling-height (6m) cult statue of Poseidon, facing the entrance. Little remains of the interior elements, as they were often made of less durable materials such as wood. How the statue looked is up for debate. Scholars have argued that it may have resembled contemporary statues and other depictions of the god, wielding a trident, which he used to stir up storms.

Archaeological excavations at the site in the late 19th and early 20th centuries uncovered numerous artifacts and offerings, including terracotta figurines, seals, scarabs, and amulets, as well as the famous “Sounion Kouros,” a 3m-tall marble statue of a young man, dated to around 600 BC (currently on display at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens).

© Public domain

© Public domain

The Legend of King Aegeus

In Greek mythology, Cape Sounion is where Aegeus (“goat man”), an early king of Athens, leapt to his death, thus giving his name to the Aegean Sea. Aegeus, anxiously looking out from Sounion, despaired when he saw a black sail on his son Theseus’ ship, returning from Crete. This led him to believe that his son had been killed by the dreaded Minotaur, a half man and half bull monster that lurked in the labyrinth of Knossos.

Theseus had, in fact, slain the Minotaur, with the help of Ariadne, the daughter of the Cretan king, Minos. Prior to leaving Athens, he had agreed with his father that if he survived, he would hoist a white sail. He tragically forgot to replace the black sail, and his father hurled himself off the cliff into the sea.

An early literary reference to Sounion is made in Homer’s “Odyssey” (c. 8th century BC), which recounts the heroic exploits of Odysseus on his 10-year voyage home to Ithaca from the war at Troy, often at the mercy of the sea god, Poseidon. In Book III of the epic poem, we learn about the helmsman of the ship of king Menelaus of Sparta, the brother of Agamemnon, commander of the Greek forces at Troy. Menelaus’ helmsman died at his post while rounding “holy Sounion, headland of the Athenians.” Menelaus and his crew then beached their ship at Sounion to cremate their fallen comrade on a funeral pyre.

© Public domain

Mysticism and Power

A popular day trip for tourists from Athens, Sounion provides awe-inspiring vistas of the sea and the nearby islands, especially at sunset. Along with the Athenian Acropolis and the Parthenon, Sounion draws together all the quintessential ingredients of a Classical Greek site: a dramatic landscape, azure blue sea, and an ancient monument imbued with mysticism and power.

Over the centuries, countless travellers and artists have been drawn to the site, prompting some to carve their names into the marble of the Temple. Perhaps the most famous is that of Lord Byron, who, at some point in 1810-1811, carved his name into the base of one of the columns his carefully etched name, which is still visible today.