After returning from a visit to Delos in May 1864, Leon Terrier, a member of the French School of Athens (Ecole Francaise d’Athenes, or EFA), stressed that if the antiquities on the sacred Cyclades island were allowed to be destroyed, the world would be left with a void that could never be filled. His warning prompted an excavation program that began in 1873, with the cave on the Cynthian Hill. Four years later, the school’s Jean Theophile Homolle began excavating the Sanctuary of Apollo and the surrounding area, the Poros Temple and the Oikos of the Naxians.

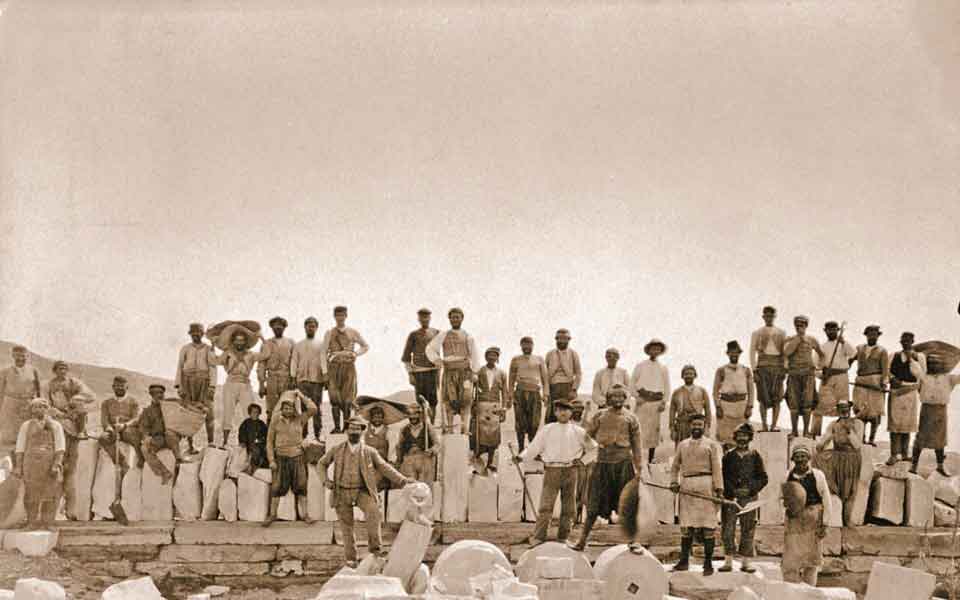

“The first archaeologists to arrive on the island were exceptionally well-educated, they spoke Ancient Greek and Latin, they knew Delos’ history from the accounts of Herodotus and Thucydides, but they had no experience in the field and absolutely no idea of what they were about to encounter,” says EFA Director Veronique Chankowski. What they encountered was very tough working conditions.

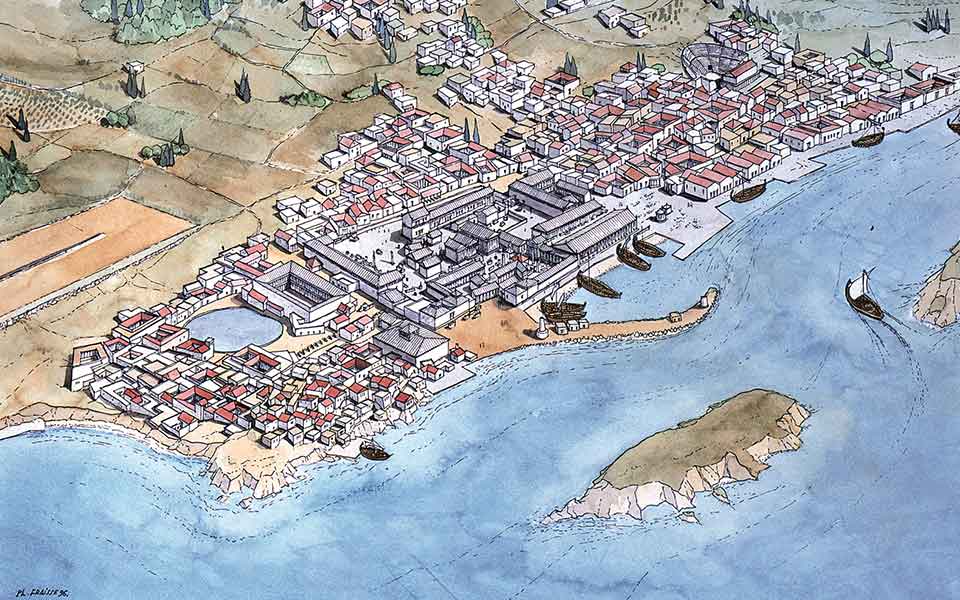

For several years, the researchers would cross over from Mykonos on a boat owned by the school and return in the evening as there was nowhere to stay on Delos. Mykonos also supplied them with food, materials and labor. As their work progressed, the excavations expanded to the area of the theater, the stream of Inopos, the coastal stretch, the Agora of the Italians, the Koinon of the Poseidoniasts from Beirut and the Gymnasium. As the excavations intensified, the construction of some kind of accommodation became imperative.

© French School of Athens

The first residence to be built consisted of just one room and was referred to as “chez Homolle,” though more were added later, of course, to cover the needs of all the members of the school who spent long stretches of time on the island. These basic accommodations did not have electricity until 1992, while the water used on a regular basis for purposes other than drinking by the researchers and workmen is, to this day, pumped from an ancient well. Even the leisure activities they engage in when they’re not working are more or less the same: conversation, walks, swimming, fishing, some farming and reading.

“When you get in tune with the rhythm of the island, you realize that it is a life in synchronicity with the past,” explains Chankowski, who has spent many months studying the history of the port of Delos and its contribution to the island’s economy and its extroverted outlook.

“The water coming from the wells, the homes from ancient times that had the same view as you have today from your room, even the way you spend your day reminds you that you are part of this journey into the past. The books you come across in the archaeologists’ houses contain notes written by people who sat at the same spot where you’re sitting a century later,” she says.

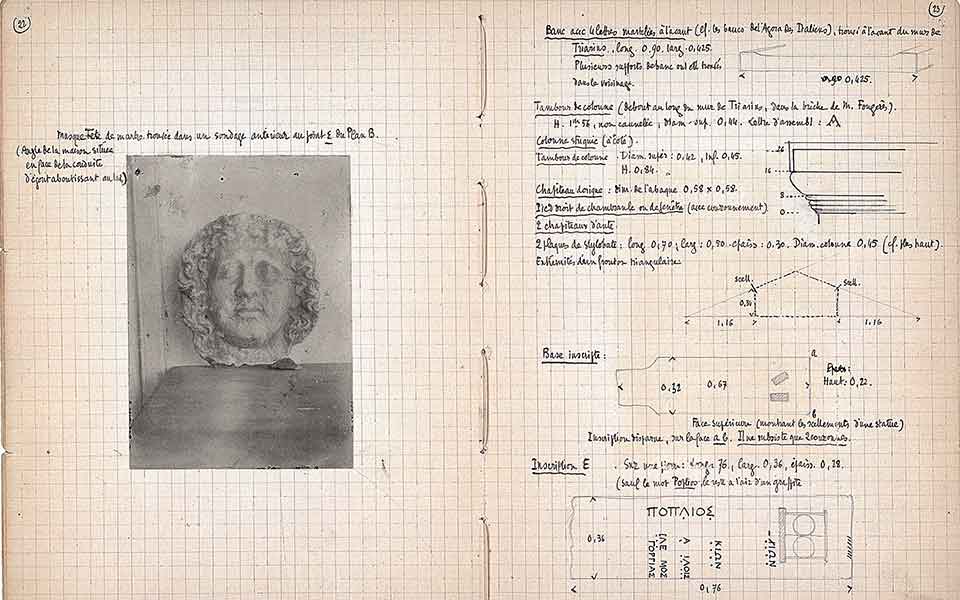

© French School of Athens

Chankowski, archaeologist Jean-Charles Moretti and Hellenic studies professor Cecile Durvye are the curators of the main exhibition of “Delos 150,” to be hosted in the school’s beautiful garden from Thursday to November 6. Photographic material concerning the fieldwork, snapshots of the challenging daily life of the excavation team members, maps, illustrations, handwritten notes and plans for the restoration of ancient ruins reveal the methods, tools and significant findings of excavations on an island that stood at the center of the Mediterranean’s commercial, cultural and political life for a very long period. They also capture the enthusiasm that came with each new discovery.

The exhibition presents the systematic excavations that were carried out on the island thanks to an annual grant of 50,000 Francs from the wealthy French-American entrepreneur and antiquarian Joseph Florimond Loubat. This donation was repeated every year until World War I, on one condition: that the donor was informed of the exact volume of dirt removed and money spent.

The material also refers to the creation of the Archaeological Museum of Mykonos and Delos in the early 20th century – until then, artifacts were kept in various homes in Mykonos under the stewardship of the island’s mayor and teacher – as well and showcasing the skills of the archaeologists in other activities like painting, drawing and photography.

The school’s focus now is on digitizing its archive and offering open access to it, but also to protecting the marvelous archaeological site. “The rising sea level makes it imperative that we move fast. There is no second Delos,” stresses Chankowski.

For more information, contact the French School of Athens at Tel. (+30) 210.367.9900, or visit the website efa.gr.

This article was previously published at ekathimerini.com.