8 Hidden Greek Museums Just Steps from the...

From olive presses and traditional costumes...

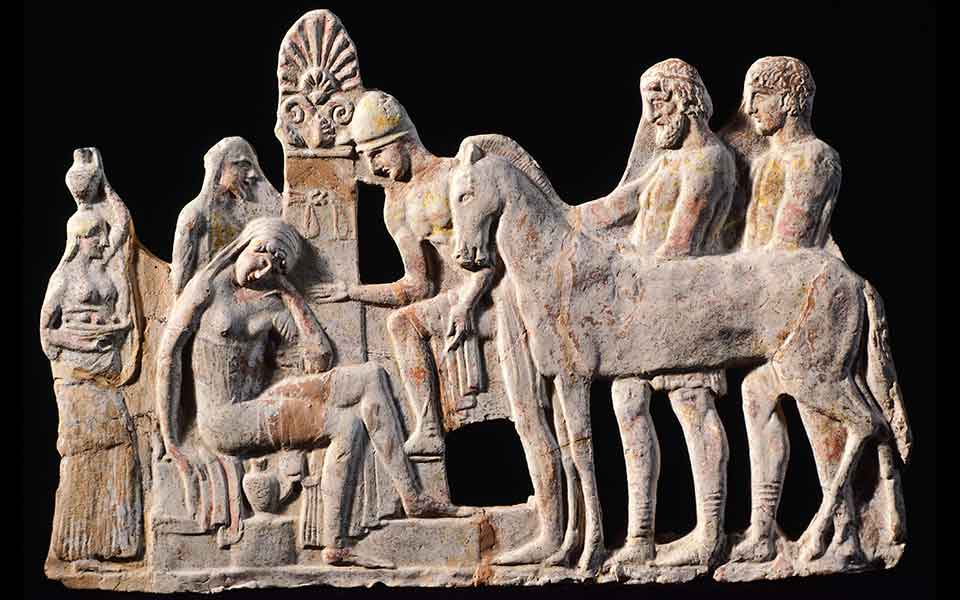

Electra (seated) and Orestes (leaning) mourning at their father Agamemnon’s grave, 470-460 BC.

© Kanellopoulos Museum, Athens

One of the great benefits of living in Athens is being able to appreciate firsthand the efforts of its dynamic community of Greek and international scholars and institutions that regularly shed light on Greece’s fascinating and inspiring past. Thanks to the temporary exhibition and accompanying lecture series “Hippos – The Horse in Ancient Athens,” presented in 2022 by art historian Jenifer Neils of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), the significance of horses (“hippoi”) in daily life in ancient Athens can now be more clearly perceived than ever before.

If you’re looking for refreshing insights into the thoughts and habits of ancient Greeks, and you’re seeking a book to assist you, then that exhibition’s follow-up volume of essays, published under the same title and with a lengthy roster of specialist contributors, should be at the top of your list. Perhaps the book’s greatest takeaway is that horses and horse imagery, together with what they symbolized, seem to have permeated almost every aspect and level of ancient Athenian society.

Horse of the moon goddess Selene, from the Parthenon’s east pediment in Athens, 5th century BC.

© British Museum

Sophocles, in the late 5th century BC, calls Attica, particularly the broad fields and groves of Kolonos Hippeios beside Plato’s Academy north of the Athenian Agora, “this land of fine horses.” Indeed, according to Neils, horses were the most admired and prized animals in ancient Greece. Many of us are likely already aware that horses were a common sight in ancient Athens – they’re all over the Parthenon, after all, and they frequently appear on painted vases – but when all the archaeological and historical threads concerning horses and horsemanship are woven together, the richly hued tapestry that results is surprisingly comprehensive and revealing.

Horses were used by the ancient Greeks for warfare and for frontier defense, in sacred processions and in marital and funerary rituals; they took part in racing and other equestrian competitions, and various public displays. They were even employed as live “extras” in theatrical productions. In the performance of “The Persians” by Aeschylus in 472 BC, The Queen Mother entered riding in a horse-drawn carriage; her regal team then remained standing in the orchestra, likely snorting and nervously shuffling their hooved feet, for nearly 400 lines. Horses frequently featured in Greek drama, as well as in mythology: one might recall Pegasus, the winged horse, or the sky-traversing chariot teams of Helios (Sun) and Selene (Moon). All in all, horses in ancient Athens fulfilled military, religious, social, economic, and cultural roles.

A relief commemorating victorious horses and riders of the Leontis tribe, in a Panathenaic “anthippasia,” a mock cavalry fight, early 4th century BC.

© Athenian Agora Museum

The extraordinary importance of horses and their special treatment in ancient times was underscored in 2012 with the discovery of more than fifteen horse burials in Nea Faliro during construction of the new Stavros Niarchos Cultural Center. Ironically, it was the modern-era Faliro racehorse track (which closed in 2004), on top of which the new cultural center was later built, that had covered and preserved these magnificent ancient horse skeletons in excellent condition. Mostly adults, the horses were laid to rest in particular positions, posed as if galloping, jumping or “proudly trotting.” To achieve this, the burial crews sliced the stiff equine corpses’ shoulders and legs to allow flexibility in their positioning. Deep cut marks on the bones were not signs of battle wounds or racing injuries, but of deliberate treatment as part of a funerary ritual.

These horses – likely dating to the Archaic-Classical era – were not broken-down nags, wedged into small pits at the periphery of ancient Phaleron’s cemetery (8th-4th century BC), but fine specimens still in their prime, interred at the same level and in among the skeletal remains of deceased humans – apparently as respected funerary sacrifices. Their careful burial, near the ancient hippodrome at Phaleron, is proof of the esteem granted them by the ancient Athenians, who valued their beauty, their physical performance, and their social significance as tokens of wealth and status.

Achilles speaks with his god-sent horses before battle, a scene from Homer’s Iliad; by the Nearchos painter, kantharos fragment, about 550 BC.

© National Archaeological Museum

In Europe, the presence of wild horses can be confirmed by Palaeolithic cave paintings from tens of thousands of years ago. Domesticated horses, however, only appeared in the 4th millennium BC in Asia, eventually spreading westward into Anatolia and presumably Thrace, along with other areas of the Greek mainland, beginning about 2200-2000 BC. In the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600-1100 BC), horses and chariots appear in pictorial and Linear B archival sources (such as those from Knossos and Pylos) in connection with warfare, hunting, and processions. On Mycenaean chariot kraters, wheels with four spokes are the norm, while Homer relates that Hera’s Ionian-style chariot ran on eight-spoked wheels. Formal horse burials, sometimes in pairs, are known from numerous Late Bronze Age sites, including Ialysos, Marathon, Argos and Dendra. Occasionally, drinking cups (kylikes) were placed in these burials, implying that horses were well respected and “toasted” at their funerals.

During the Iron Age (post-1100 BC), the earliest horse depicted in Athenian art may be one on a Proto-Geometric amphora (ca. 950 BC) recovered at the Kerameikos cemetery. Over the next two centuries, horses became ubiquitous on painted funerary vases, sometimes shown pulling chariots with warriors or funeral carriages in “ekphora” scenes. Small terra cotta horse figurines also served as popular grave goods, along with horse-handled pyxides (early 700s to ca. 600 BC), which are especially characteristic of the graves of high-status women and which may have held perishable materials intended for use in the afterlife.

Black-figure Archaic vase paintings often show horses being trained, exercised or groomed. About 599 BC, a distinctive vase type appeared in Athens, the “horse-head amphora.” These specialized containers, continuing until about 550 BC, may have been either status symbols produced solely for graves to indicate the wealth of the deceased though equine imagery; or standardized prizes for equestrian competitions – similar to the distinctive oil-filled amphorae that were adopted for the Greater Panathenaia festival in 566 BC. By the middle/late 6th century BC, horse scenes on vases were filled with evocative details, including brands or owners’ marks on the animals’ rumps (e.g., snakes); apotropaic necklaces to ward off evil, a traditional practice still seen today; or horses’ names scratched beside their images, reflecting either their color or appearance – such as Xanthos (Bay/reddish-brown), Phaethon (Bright-coat), Korax (Raven), and Melanthis (Black Flower) – or their temperament or mannerisms: Thrasos (Courage), Podargos (Swift-foot), Aethon (Flash), or Kyllaros (Hermit Crab), the last perhaps for a horse who was shy or liked to move in a sideways direction.

Athens’ earliest silver drachmae (550-510 BC), minted under the Peisistratids, similarly displayed images of horses. Circulating from hand to hand, they served as visual reminders of the civic contributions of elite Athenians, while also further emphasizing the regard and economic value that horses held in Attic culture and society.

In 5th century BC Athens, horse-related images or epigraphic references could be found everywhere, from Classical red-figure vases and carved funeral stelai to votive sculptures, decorative marble reliefs on temples, bronze and clay figurines, coins, and dedicatory inscriptions. During the subsequent Hellenistic era, increasingly realistic equine statues were crafted, as illustrated by the bronze Jockey of Artemision (ca. 150/140 BC) astride his galloping steed.

Poseidon, god of the sea, riding a winged seahorse; Attic white-ground lekythos, from Gela; the Athenian painter, early 5th century BC.

© Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

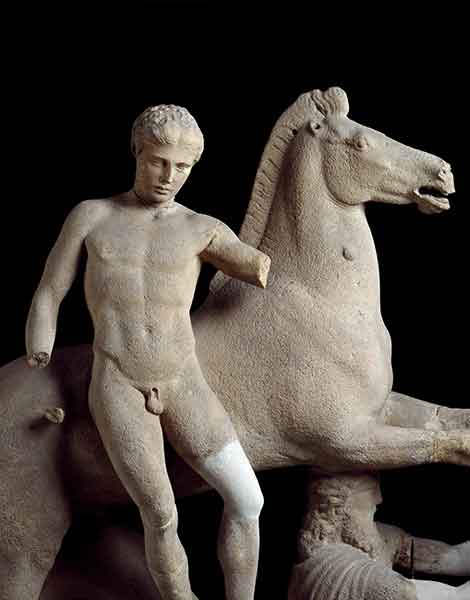

One of the Dioscuri dismounts his horse; from a temple pediment at Epizephyrian Locris, Magna Graecia; 5th century BC.

© National Archaeological Museum of Reggio Calabria

Horses and hippotrophia, the breeding and keeping of horses, had long been associated with Attica’s more affluent citizens and old established families, including the Peisistratids, Philaids, and Alcmaeonids. To be a member of the Hippeis (Knights), the second-highest social class following Solon’s democratic reforms of 592/1 BC, one had to produce an annual income of 300 measures of grain – which also meant such citizens possessed the financial freedom to be able to buy and care for horses. Chariots and horses took on aristocratic associations; in both visual art and Homeric literature, they became familiar reminders of the foregoing “Heroic Age” in the late prehistoric era. With the rise of hoplite warfare through Geometric and Archaic times, chariots largely disappeared from the battlefield, instead becoming a status symbol often used in funeral processions and competitive games, or in wedding rites to convey the bride to her new home.

Giving one’s children horse-related names became a widespread practice within aristocratic families, one which also filtered down to the lower classes. The tyrant Peisistratus, for example, named his sons “Hippias” and “Hipparchos.” The elegant Rampin Rider (ca. 550 BC; Acropolis Museum) may have been one of a pair of sculpted horsemen meant to depict these high-status youths; alternatively, it could have represented one of the mythical Dioscuri, Castor and Polydeuces, “the riders of swift steeds.”

By 450-400 BC, hippic names – such as Xanthippos (the father of Pericles), Philippos, Melanippos, Zeuxippos, Hippocrates, and hundreds of other similar appellations – became one of the most popular name-forms in the Greek world. Under Pericles, democratic Athens’ “Golden Age” was also the era when Attic horse culture reached its zenith. Wealthy horse owners (hippotrophoi) and knights (hippeis) of the cavalry were among the most prominent citizens, frequently observed at public processions, exercising their mounts at the Kolonos Hippeios, or at competitions, including those of the Olympic and Panathenaia games. Youths were portrayed as “horse-crazy” in both Clouds and Knights, two ancient comedies by Aristophanes. From playing with small hippic figurine-toys as children, they grew up eager to be given a horse or to work as squires (knight’s attendant, horse trainer/exerciser), jockeys, and grooms. Professional charioteers were also common, as a hippotrophos himself rarely drove his own chariot in races. Being a horse owner or a knight was a mark of prestige, sometimes vaunted in public. Theophrastus colorfully describes “The Man of Petty Ambitions” as the person who, having completed his knightly duties, “will give…his accoutrements to his slave to carry home, but…will walk about the agora in his spurs.”

Silver decadrachm of Syracuse: a charioteer driving a quadriga (4-horse chariot), with Nike (Victory) flying above to crown him, 404-390 BC.

© Ashmolean Museum

Perhaps nothing enthused ancient Greek audiences more than the sight of competing horse-drawn chariots or race horses blazing down the track. By the 7th century BC, the four-horse chariot contest (tethrippon, introduced 680 BC) and the race for individual horses (keles, 648 BC) had become popular events at Olympia. The two-horse chariot competition (synoris) was added in 408 BC. Martial events or public displays included the “apobates,” perhaps invented about 510 BC, in which an armed warrior jumped out of and remounted a moving chariot; the javelin throw from horseback (from late 5th century BC); and the stirring “Anthipassia,” a mock chariot battle described in the 4th century BC by Xenophon, in which two opposing groups, each consisting of five teams from the ten Attic tribes, charged and passed through each other’s ranks three times.

Victory prizes in these events typically went to the horse owners, not the drivers or jockeys. Nevertheless, chariot drivers occasionally appear in votive offerings, epitomized by the well-known Charioteer of Delphi (470s BC). Inscribed lists of Athenian victors initially reflected aristocratic family backgrounds, but gradually became more democratic. Among the most celebrated victors were Kimon, whose tethrippon triumphed at three consecutive Olympic games (536-528 BC); and Alcibiades who, according to Thucydides, entered seven chariots at Olympia in 416 BC, where his teams finished first, second, and fourth. He also triumphed at Delphi, Nemea, and Athens in 418 BC, ultimately accumulating a lifetime total of 82 Panathenaic amphorae. The Romans, too, had a passion for chariot racing, as Nero demonstrated when he personally visited Olympia in AD 67 and drove his own chariot, pulled by ten horses! Although he fell out onto the track mid-race, he was still awarded the victor’s olive-branch crown. A particularly successful Roman-era Athenian, Titus Domitius Prometheus, received the wreath in chariot racing at all four Panhellenic games (Olympia, Delphi, Nemea and Isthmia) in AD 235-41.

A team of horses form the handle of a Geometric Attic pyxis, a women’s cosmetics or jewelry box, 730-720 BC.

© Art Institute of Chicago

Two historical sources are especially informative on horses and their care in ancient Athens: a mysterious horse trainer, art critic, and patron of the arts known as Simon; and the Athenian historian, philosopher, military man, and gentleman farmer Xenophon, who based his own hippic writings on Simon’s fundamental and now largely lost treatise. Simon, a respected equine authority who enjoyed some celebrity in 5th century BC Athens, wrote a manual for owners and trainers that still holds true today, observes classicist Anne McCabe. Simon advises that, ideally, horses should be acquired in Thessaly, be well-proportioned, exhibit an evenly colored mane, and have hooves that ring like cymbals. Regarding their shape, he uses the same word – “symmetria” – as the sculptor Polycleitus did for statues to describe their proportional harmony. Simon was also known for criticizing the famous painter Mikon, who had depicted horses with eyelashes on their lower eyelids (where they have none!), and for dedicating a bronze horse statue at the City Eleusinion in the Athenian Agora beside the Panathenaic Way.

Xenophon expands on Simon’s guidance in his own book, On the Art of Horsemanship. The former Greek mercenary and general offers a wide array of insightful advice, from choosing, breaking, and training a horse to what tack and proper facilities are required. In handling, he says, one must have a knowledgeable groom, and horses should be taught to be calm with a chirp of the lips or roused with a cluck of the tongue. They should be readied for war, learning not to overreact to wild shouts or shrill battle trumpets. Gentleness is paramount, since “a horse does not perform well under coercion, as a dancer would not if whipped and spurred… ” Overall, horses in ancient Athens were treated very well; fed grasses, grains, and even wine; provided for twice daily with “breakfast” and “dinner;” and meticulously groomed, especially their manes. Xenophon proclaims “…a prancing horse is a thing so graceful, terrible and astonishing that it rivets the gaze of all beholders, young and old alike.”

No fewer than 257 horses – including 143 cavalry horses and numerous drawn chariots – appear on the Parthenon, decorating its pediments, metopes, frieze, and cult statue base.

© British Museum

The knights of the cavalry were a particular source of Athenian pride. In the mid-5th century BC, they numbered 300, counting 30 members from each Attic tribe. In Pericles’ time, the cavalry was expanded to 1000 horsemen, two hipparchs (cavalry commanders), and 200 mounted archers (hippotochotai), who received twice the daily pay of the hippeis. The knights assembled and exercised their horses at Kolonos Hippeios where, Sophocles relates, Poseidon first introduced the skill of horsemanship. This bucolic wooded area adorned with small shrines and altars was particularly sacred to Poseidon Hippios and Athena Hippia, the Athenian cavalry’s patron deities. Poseidon was the god most closely associated with hippoi, and swift ships running at sea are described by Homer as “horses of the deep.” An altar for Poseidon Hippios also existed at Olympia, where a bronze dolphin was used as a signal in the hippodrome to start the chariot and equestrian races.

The Athenian Agora was another place for the public to catch a view of the cavalry, with the knights galloping past or trotting grandly along the Panathenaic Way. The commanders had their headquarters (Hipparcheion) in its northwest corner. There, a cache of inscribed lead strips discarded in a well attests to the annual assessment of the cavalry’s mounts and their value by the Athenian state, which, in Periclean times, assisted knights in buying, maintaining, and even insuring their horses.

The Athenian cavalry was expanded to 1000 horsemen during the time of Pericles.

© British Museum

Like Kolonos, the Acropolis was sacred to both Poseidon and Athena in their Hippios/Hippia forms. The primordial struggle between the deities for dominance in Athens, prominently displayed in the sculpted scene of their contest in the Parthenon’s west pediment, is echoed in their similarly competitive roles with regard to horses. According to mythographers, Poseidon produced the first wild horse, but wise Athena invented the bridle to temper and tame the spirited beast. She also conceived the Argives’ ruse of the Trojan Horse. Despite Poseidon’s hippic primacy, he is overshadowed by Athena in this case as well in regards to the sculpted imagery of the Parthenon. No fewer than 257 horses – including 143 cavalry horses and numerous drawn chariots – appear on the goddess’ temple, decorating its pediments, metopes, frieze, and cult statue base. Some riders wear Thracian dress, reflecting the Athenians’ admiration for a wild, resource-rich region renowned for its own age-old hippic culture and superior horsemanship.

Sparta was likewise respected for its lifestyle and its use of horses, particularly by the Athenian aristocracy. This sympathy is apparent in the popularity of the Dioscuri, who were mythically linked to the Lacedaemonians. Homer calls Castor “the horse-tamer,” while in Athens the twins were the “Anakes,” worshipped at their shrine (Anakeion) near the Acropolis. Horses and hippic creatures were familiar characters in Greek myth and legend, from the half-man, half-horse centaurs to flying Pegasus – sired by Poseidon with Medusa, but later tamed by Bellerophon with the aid of Athena. Perhaps the best-remembered mortal horse from Greek antiquity was Bucephalus, Alexander the Great’s beloved, long-serving steed, who finally died at the age of thirty and was ceremoniously buried after the Battle of Hydaspes in 326 BC.

From olive presses and traditional costumes...

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

From a mysterious Minoan structure to...

Beneath the busy streets of modern...