Held every four years at the sacred sanctuary of Olympia in the western Peloponnese, dedicated to the worship of the god Zeus, the Ancient Olympic Games continued without interruption for nearly 1,200 years, from 776 BC to AD 393, leaving behind an indelible mark on human civilization.

While there were no medals and no women at the ancient Olympics, but one female figure from ancient Greek mythology has been at the heart of the modern revival of the Games since 1896, appearing, in one form or another, on nearly every medal awarded to the world’s most accomplished athletes. Who was she? What did she embody for the ancient Greeks? And why is she still important today?

© Shutterstock

Beautiful Virtue

According to the Classical poet Pindar (c. 522-443 BC), the Olympic Games were founded by the divine hero Hercules (Heracles), the son of Zeus, as a means to honor his father. Another legend attributes their foundation to Pelops, a mythical king who organized the games in commemoration of his victory over king Oenomaus (literally “wine man”) of Pisa in a chariot race.

Religious devotion was an integral part of the ancient Games. The event was marked by elaborate ceremonies and rituals dedicated to the gods, particularly Zeus, king of the Olympians. Participants and spectators alike engaged in sacrifices, prayers, and processions to honor the deities and seek their favor for the success of the Games.

One core aspect of the ancient Olympic ethos was the concept of “agon,” or competition. The games aimed to showcase the physical prowess and skill of the participating athletes, who hailed from various Greek city-states and colonies. The athletes competed in a variety of disciplines, including running, jumping, throwing, wrestling, and chariot racing. The emphasis was on individual achievement and personal excellence, with winners being awarded an olive wreath, or “kotinos,” and achieving great honor and recognition in their respective communities.

The ancient Olympics were not merely a showcase of athletic ability but also a celebration of the ideal of “kalos kagathos,” literally “beautiful virtue,” which referred to the harmony of physical and moral virtues, and gentlemanly conduct. The games were open to freeborn Greek men who met specific eligibility criteria, and participants were expected to adhere to strict rules of fair play, respect, and integrity. Cheating and misconduct were severely punished, and the Olympic Truce was observed, ensuring a temporary cessation of hostilities among Greek city-states during the games.

© Public domain

1896 and the Modern Revival

The revival of the Olympic Games in 1896 was driven by a desire to recapture the spirit and traditions of the ancient Games; the pursuit of healthy rivalry, noble competition, and fair play. Attributed to the efforts of Pierre de Coubertin (1863-1937), a French educator and historian who is widely regarded as the father of the modern Olympic Games, the rationale was to promote international understanding and cooperation in a rapidly changing world. Coubertin saw sports and athletic competition as a means to bring people from different nations together on a common platform, transcending political and cultural boundaries: the Olympic Games as an enduring symbol of peace and unity among nations.

Coubertin, who was born into a French aristocratic family, was also a strong advocate for physical education and believed that sports should be an integral part of the educational system. He saw the Olympic Games as an opportunity to encourage the importance of physical activity and fitness, particularly in an era that was witnessing rampant industrialization and a decline in physical well-being.

At the ancient Olympics, triumphant athletes were awarded a circular or horseshoe-shaped olive wreath, made from the branches of wild olive trees that grew at the sacred sanctuary of Olympia. At the inaugural modern Games in Athens in 1896, the I Olympiad, winning athletes received a silver medal and an olive branch, while runners-up were given a laurel branch and a bronze or copper medal. The tradition of being awarded a medal had begun, but what did this first medal look like?

© Public domain

Gold, Silver and Bronze

The first medal to be awarded at the modern Olympic Games was designed by French sculptor Jules-Clément Chaplain (1839-1909), who, along with French medallist Louis Oscar Roty (1846-1911), was one of the founders of the Art Nouveau movement.

With a diameter of 48mm, the obverse (front) of the medal bears the striking image of Zeus, heavily bearded and with a piercing gaze fixed on the viewer, his outstretched hand holding a globe with a winged female figure on it. The inscription “ΟΛΥΜΠΙΑ” runs vertically down the lefthand side. The reverse features a richly detailed relief of the Acropolis of Athens, the enduring symbol of Classical Greece.

The winged female figure, holding an olive branch and wearing a light, flowing chiton (a simple, tunic-like garment), is none other than Nike, the Winged Goddess of Victory, a divine being associated with triumph, success, and the rewarding of excellence. Typically depicted in ancient Greek art as a beautiful winged woman, often shown in mid-flight, her representation embodied the concept of a swift and glorious victory, whether on the battlefield, or in artistic, musical, or athletic competition.

Nike featured even more prominently on the medal of the II Olympiad in Paris, 1900, taking up the entire obverse side, arms raised, and holding laurel branches in both hands. In the background, underneath the goddess, a view of the city of Paris and the monuments of the famous Universal Exhibition can be seen. At the Games, the winners medals were made of gilt silver, runners up silver, and third-placed athletes were awarded a bronze medal. Designed by French sculptor and engraver, Frédéric-Charles Victor de Vernon (1858-1912), the 1900 Paris medal is notable for being the only time rectangular medals were awarded.

The tradition of awarding gold, silver and bronze medals for the first three places was first introduced at the III Olympiad in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1904, a custom that continues to this day.

As for Nike, she has appeared on the obverse side of every Summer Olympic medal except for four Games: 1908 (London), 1912 (Stockholm), 1920 (Antwerp), and 1924 (Paris) – no Games were held in 1916 due to World War One. She returned for the IX Olympiad in 1928, held in Amsterdam, and remained essentially unchanged until the end of the 20th century: a seated chiton-clad goddess, her right arm aloft holding a winner’s wreath, and an ear of corn in her left hand.

Breaking with tradition, Greek jewelry designer Elena Votsi, who won the competition to re-design the Summer Olympics Medal for the Athens Games in 2004, opted to depict the goddess flying into the all-marble Panathenaic Stadium, where the modern Games were first revived. Reflecting the Greek character of the Games, the reverse side of the medal depicts the eternal flame, lit in Olympia, and the opening lines of Pindar’s Eighth Olympic Ode, composed in 460 BC.

Since 2004, Nike has remained in the same characteristic pose, bringing victory to the best athlete.

© Public domain

© Piblic domain

Nike, the Winged Goddess of Victory

According to the Greek epic poet Hesiod, writing in the 8th century BC, Nike was the daughter of the Titan Pallas and the goddess Styx. (In another tradition, she was the daughter of Ares, the god of war). She had siblings who personified other virtues and concepts, such as Zelos (rivalry), Kratos (strength), and Bia (force). Nike was considered a close companion of the chief deity Zeus and was frequently seen accompanying him. Her Roman equivalent was Victoria.

Nike was a significant figure in ancient Greek culture and was highly revered in various contexts, including warfare, athletics, and competitive games. She was believed to bring success and good fortune to those who worshiped her or sought her favor. Her presence was especially felt during moments of victory and celebration.

Nike’s influence extended beyond mythology and found expression in various forms of art and architecture. One of the most famous representations of Nike is the statue of the Winged Victory of Samothrace. This masterpiece, dated to the beginning of the 2nd century BC, is a marble sculpture that depicts Nike standing on the prow of a ship, her wings spread wide.

In ancient Athens, Nike was worshipped alongside the goddess Athena, where she was called “Athena Nike.” A cult of the goddess was operating as early as the 6th century BC and a small temple was erected to the goddess on the southwest corner of the Acropolis, built around 420 BC.

The Spirit of Inclusion

The 1928 Amsterdam Games, officially known as the Games of the IX Olympiad, not only marked the reintroduction of the goddess Nike on the winner’s medal, but also a number of crucial innovations that left a lasting impact on the Olympic movement, including the Olympic flame being lit the stadium and the development of a new and more accurate method of timing track and field events.

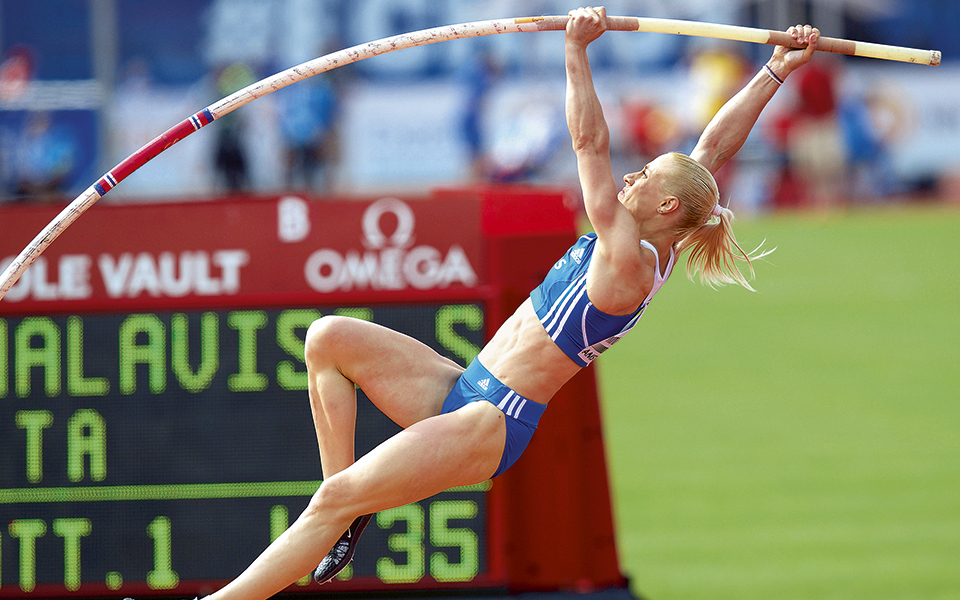

Most importantly, these Games also marked the first appearance of women’s athletics, including events such as the 100m, 800m, and high jump. This represented a major step forward for gender equality in Olympic competition, and was aptly commemorated by the reintroduction of Nike in the design of the medal.

Indeed, the inclusion of women’s athletics in 1928, reflecting the progressive spirit of the time, paved the way for the further expansion of women’s participation in Olympic sports in subsequent editions, and was seen as a major victory for women’s rights.