In the far south of the Greek mainland, off the southeast coast of Laconia, the sprawling remains of a vast prehistoric settlement, abandoned some 3,000 years ago, lie just below the surface of the sea.

Located at the western entrance of Vatika Bay, a mere 20m off Pounta Beach, the submerged city of Pavlopetri is one of the most famous underwater archaeological sites in the world. Careful analysis of its extant remains by archaeologists over a decade ago, covering an area of nearly 50,000 square meters (equivalent to seven soccer pitches), has provided unparalleled insight into the life of an Aegean coastal town, before its sudden and as yet unexplained abandonment.

What makes Pavlopetri so remarkable is that it boasts an almost complete urban plan, one of only a handful of completely submerged ancient cities ever discovered (others in the Mediterranean include Heracleion in Egypt, and Atlit Yam in Israel, among others). Its submergence and partial burial under layers of sediment has preserved much of its structural remains, including streets, buildings, courtyards, and even tombs, but seismic activity, mass tourism, and looting are a constant threat to its future preservation.

And despite nearly 50 years of research, its discoverer, Dr Nicholas Flemming, a retired marine geo-archaeologist at the Institute of Oceanography at the University of Southampton, believes the submerged city still holds many secrets.

© Shutterstock

A THRIVING URBAN CENTER

Pavlopetri, which means “Paul’s Stone” in Greek, is a direct reference to Paul the Apostle, who traveled to Greece in the 1st century to spread the word of Christianity. But its origins as a place of human habitation stretch much further back in time to the Final Neolithic, from at least the mid-4th millennium BC.

Located in the channel between the mainland Peloponnese and Elafonisos island (formerly part of the peninsula before being broken off by a devastating earthquake), the site was ideally situated for human habitation, with easy access to fertile land, fresh water, and the sea. Over time, and thanks to its naturally sheltered location, the site developed into a fishing village.

During the Bronze Age, from around 2800 BC, Pavlopetri rapidly grew in significance and complexity, evolving into a thriving urban center. Its strategic location near the tip of the Laconian peninsula gave it easy access to trade networks that plied the seaways around the southern Peloponnese, enabling it to develop into an important hub for maritime trade.

The vast quantities of pottery recovered from the site, including fragments of large “pithoi” (storage jars) and transport containers, demonstrate its role within the expanding trade networks of the Aegean Bronze Age. Analysis of these finds reveal close contacts with the palace centers of Minoan Crete, and settlements in the Cyclades and the northeast Aegean. Furthermore, the discovery of many loom weights have led archaeologists to believe the site was an important center for textile production.

Using advanced underwater mapping techniques, archaeologists have also revealed aspects of the settlement’s urban design, most notably from the Mycenaean period (Late Bronze Age, c. 1750-1050 BC), inlcuding straight, narrow streets, courtyards, and the foundations of at least 15 buildings, each consisting of multiple rooms (as many as 12 in some cases). Remarkably, the remains of two chamber tombs and 37 cist graves were also discovered, part of an extensive Early Bronze Age cemetery that can be traced to the adjacent shore, beyond the boundaries of the settlement.

One of the most extraordinary aspects of Pavlopetri was its advanced water management system, similar to the drainage systems discovered at Bronze Age Akrotiri on Santorini. The site featured a highly developed network of channels and terracotta pipes that would have effectively managed water flow and sanitation throughout the settlement.

Around the 11th century BC, following the systems collapse of palatial centers throughout Greece and the eastern Mediterranean, Pavlopetri suddenly went into decline. The exact reasons why the city was abandoned is still subject to debate, but it’s believed that a combination of factors, such as socio-political changes, environmental shifts (subsidence, earthquakes), and/or external influences, may have contributed to its demise.

UNDER THE MEDITERRANEAN

Pavlopetri was periodically re-occupied during the Classical and Hellenistic periods, and may have been exploited in Late Antiquity for its Murex (marine gastropods), used for the production of purple dye, but it never rekindled its former glory. As the site gradually sank beneath the waves due to the continual downward subsidence, Pavlopetri faded from memory.

Submerged archaeological remains were first identified in 1904 by Greek geologist Fokion Negris, but their significance were not widely recognized at the time. It was not until 1967, when British marine geo-archaeologist Nicholas Flemming visited the area and confirmed the existence of the prehistoric settlement at the western entrance of Vatika Bay, that Pavlopetri was brought to the attention of the world.

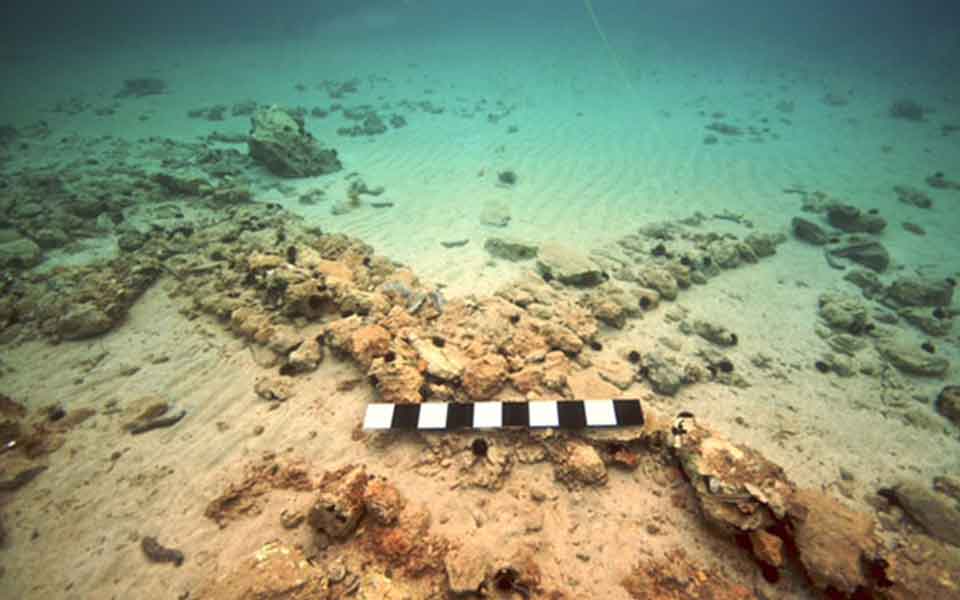

The following year, a team of diving archaeologists from the University of Cambridge launched an underwater survey using simple measuring tapes and a fixed grid system. Over the course of six weeks, they recorded an area of c. 300 x 100m, revealing large building complexes, courtyards, streets and tombs lying in 1-4m of water. The initial results captured the attention of researchers and underwater archaeologists, who recognized the immense potential for studying a near-intact submerged city.

In 2008, 40 years after the original Cambridge survey, Nicholas Flemming returned to the site with researchers from the University of Nottingham, Chrysanthi Gallou and Jon Henderson. In collaboration with the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, a new five-year project (2009-2013) was launched using state-of-the-art digital survey equipment, including remote-operated vehicles (ROVs), photogrammetry, and sector-scanning sonar technology.

In an interview in 2011, Henderson commented on the general aims of the project: “The reason we’ve gone back 40 years later was to use new, cutting-edge technology, which is developing so quickly that each year of the project we’re used different techniques. Probably now, Pavlopetri is the most surveyed bit of seabed in the world…”

Over the course of the project, the Greek-UK team carried out a detailed underwater survey of the site, producing photo-realistic, three-dimensional images of the seabed, recording underwater structures to millimeter accuracy. This pioneering technique, which uses a series of stereo photo cameras over the site to create a map, is called stereo photogrammetry, and was developed by the Australian Center for Field Robotics at the University of Sydney.

The team also used acoustic techniques to achieve three-dimensional recording of the seabed, allowing the researchers to identify individual small finds, including pottery sherds.

According to Henderon, “the ability to survey submerged structures, from shipwrecks to sunken cities, quickly, accurately, and more importantly, cost effectively, is a major obstacle to the future development of underwater archaeology. I believe we now have a technique which effectively solves this problem.”

The work of the archaeological team was gathered together in the documentary film, “Pavlopetri: City Beneath the Waves,” produced by the BBC in 2011.

WHY WAS THE CITY ABANDONED?

In order to better understand the urban development of Pavlopetri in the Bronze Age, and its subsequent abandonment, the researchers needed to investigate the geomorphology of the seabed in the narrow channel between the mainland and Elafonisos island. More precisely, to establish when the isthmus connecting the mainland to the island was inundated, thus affecting the shelter for ships. The presence of the isthmus likely formed a natural embayment or lagoon, supporting seafaring and trade – the lifeblood of the city. Without it, an open channel would not provide vessels with sufficient protection from the winds.

Marine geologists agree that the city’s submergence was largely due to highly active plate tectonics, with an average rate of submergence around 1m per thousand years. As such, the abandonment of the city did not happen due to a sudden rise in sea level. Instead, it’s likely that the broader systems collapse of Bronze Age civilizations around the eastern Mediterranean, including warfare and the rapid demise of once far-reaching trade networks, was the primary reason for the city’s decline. Alternatively, a series of violent earthquakes at the end of the 2nd millennium BC may have forced the inhabitants to flee.

In any event, the need to preserve Pavlopentri for future generations is of primary concern to Greek and international heritage organizations, including the New York-based World Monuments Watch (WMF), which added the site to its list of threatened cultural sites in 2016.

Despite being formally protected under the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, submerged prehistoric sites face multiple threats, including pollution from large commercial ships, shifting sediments, and looting of artifacts from the sea floor.

In the case of Pavlopetri, the extant ruins are at risk from boats anchoring in Vatika Bay. Speaking in 2016, Nicholas Flemming discussed an initiative by the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, the Municipality of Elafonisos, and the Regional Authority of the Peloponnese to install underwater signs at the site and the possibility of creating a sea park: “The community is the best guardian for Pavlopetri and it needs to be helped,” adding that the authorities needed to be extremely careful about how they run a Bronze Age underwater site so as to prevent any damage.

The future preservation of the site may work hand-in-hand with be guided underwater tours by professional archaeologists, part of a new initiative to make submerged sites more accessible to the public, in similar vein to the 5th century BC Peristera wreck off Alonnisos.