When people think of the Palace of Knossos in northern Crete, they often think of the mysterious Minoans, Europe’s first major civilization, and the infamous Labyrinth of Greek mythology, inhabited by the fearsome half-man, half-bull Minotaur. Sir Arthur Evans, the acclaimed British archaeologist who excavated the site in the first years of the 20th century, also looms large as the man who forged much of our early understanding of Aegean prehistory.

While many people still associate Evans with the site’s initial discovery, precious few outside of Greece and the academic clique of Cretan archaeology have heard of Minos Kalokairinos, a local businessman and amateur archaeologist, who, in 1878, was the first to unearth conclusive evidence of a large Bronze Age palace at Knossos.

Even since the unveiling of his bust in 2019 at the entrance of the now world-famous archaeological site, opposite the bronze bust of Evans, Kalokairinos’ all-important contribution has remained in the shadows. Thanks to a new exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, all of that is about to change.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

“Labyrinth: Knossos, Myth & Reality,” the first UK exhibition to focus on Knossos, aims to present the full history of the legendary site, acknowledging the vital role the amateur Cretan archaeologist played in its discovery.

In a recent interview with The Guardian, Andrew Shapland, the Ashmolean’s Sir Arthur Evans Curator of Bronze Age and Classical Greece, said: “We want to set the story straight … There are moves in Greece now to give Kalokairinos credit for the discovery.”

In stark contrast to the ill-gained reputation of Lord Elgin, the Scottish nobleman who, 100 years earlier, unceremoniously wrenched the 2,500-year-old decorative sculptures from the edifice of the Parthenon in Athens, Arthur Evans is still widely admired for his excavations at Knossos, which ushered in new age of systematic archaeological enquiry.

© Publilc Domain

© Public Domain

From 1900 to 1905, Evans, who invested his entire personal wealth into the excavations, unearthed the largest archaeological site on Crete, the undisputed ceremonial and political center of Bronze Age Minoan civilization. Aided by his close associate Duncan Mackenzie, and hundreds of local workmen, the findings shook the archaeological world, including the well-preserved remains of over 1,000 interlocking rooms, paved courtyards, artisans’ workshops, food-processing areas, storage magazines, and a throne room, complete with intricately painted frescoed walls, dated to the mid-second millennium BC.

But it was Minos Kalokairinos’ hitherto unsung efforts that, over two decades earlier, first brought the site to the attention of the international archaeological community, including Heinrich Schliemann of Troy, Mycenae and Tiryns fame, and Evans himself, who, still mourning the sudden death of wife, arrived in 1894 to inspect Kalokairinos’ large collection of finds.

© Shutterstock

Exploratory excavations

The son of a rich landowner, Minos Kalokairinos had earlier embarked on a law degree at the University of Athens, but was forced to return to Crete to look after his ailing father. His initial explorations on the slopes of Kephala Hill, 5km southeast of Heraklion, began in 1877, followed by excavations in late 1878, when he made “soundings” – test pits – at 12 different locations, covering an area of 55m by 40m.

Over the course of three weeks, Kalokairinos discovered the remains of storage rooms containing pithoi (large storage jars) and a corner section of a throne hall, which was later revealed to form part of the west wing of the palace. He also noted the carving of a distinctive-looking double-axe (“labrys”) on a stone wall, a symbol of royal authority.

© Shutterstock

Unfortunately, Kalokairinos’ early endeavors were thwarted by the local government on the island, which was still under the partial control of the Ottoman empire. Fearing the artifacts would be confiscated and exported by the Turkish authorities, his exploratory excavations were immediately shut down.

Nevertheless, news of his findings sparked interest among foreign archaeologists, as many of the objects unearthed during his trial excavations were donated to museums in Greece, Paris and London.

According to William J. Stillman, an American diplomat of the time and former consul for the United States in Crete, Kalokairinos kept meticulous records of his excavations, which would have been useful for subsequent studies. In a cruel twist fate, these valuable archives, along with many of the pithoi, were lost during the Cretan insurrection of 1898, when his house in Heraklion was pillaged and burned by rioters.

The new exhibition at the Ashmolean, which opens on February 10, will feature more than 100 objects on loan from museums in Crete and Athens, presented alongside Evans’ extensive personal archive of excavation notes. While acknowledging Evans’ positive legacy at Knossos, the exhibition will give full recognition to Kalokairinos for his initial discovery of the palace ruins, whose test pits were lost during the later excavations.

It is not known why the Cretan’s contribution was downplayed and sidelined by Evans. As the island struggled for “enosis” (union) with Greece at the end of the 1890s, Evans purchased part of the area of Kephala Hill with funds from his own estate, with additional contributions from the newly formed Cretan Exploration Fund. And with the backing of the British School at Athens, excavations began in early 1900, soon after Crete gained independence from the Ottomans.

According to Shapland, “Evans may have fallen out with Kalokairinos, but his story is the opposite to Elgin’s. Elgin is demonized in Greece for taking the marbles to the British Museum whereas Sir Arthur is still celebrated because of the way he popularized Minoan culture.”

© Shutterstock

Spinning the myth

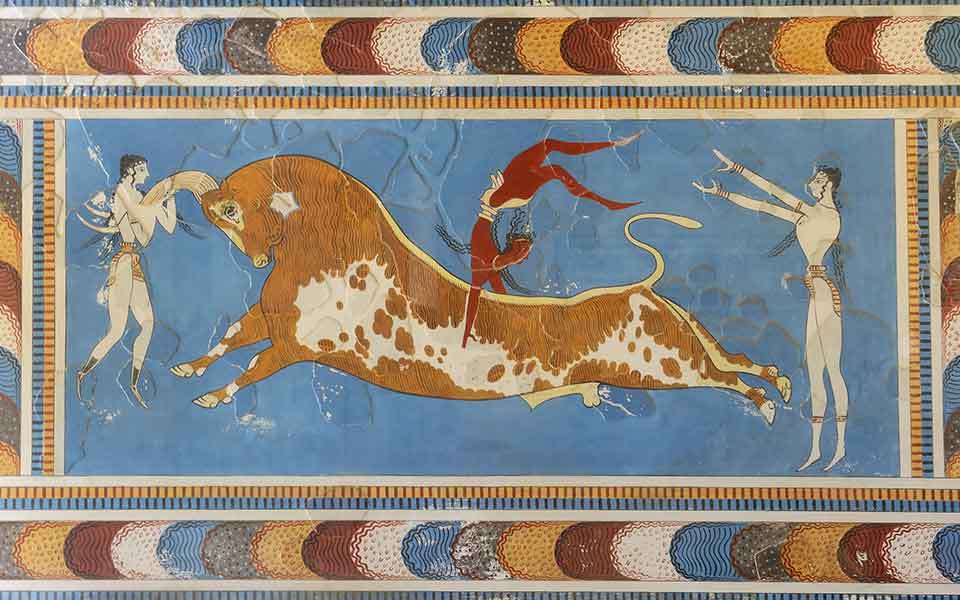

Evans, who was knighted in 1911 for his services to archaeology, believed the maze-like building plan at Knossos was reminiscent of the infamous Labyrinth, described in Greek mythology. According to the myth, the Labyrinth was built by King Minos, legendary ruler of Crete, to hold the ferocious Minotaur, a half-man, half-bull monster, the offspring of Minos’ wife Pasiphaë, and a bull.

Evans backed up these claims by the large number of bull motifs he found painted on the walls of palace. As such, he was the first to dub the civilization that inhabited Knossos “Minoan,” and the labyrinthine complex the “Palace of Minos.”

“There definitely was some sort of maze at what he called the palace, but there was no sign that people had left offerings there in that period. There are, though, tantalizing hints of the minotaur connection and frescoes of people leaping over bulls,” admits Shapland.

© Shutterstock

If there is one black mark against Evans’ reputation, it’s the controversial concrete “restorations” he undertook at the site in the 1920s, including several features not attested to in the archaeological record. These include ceilings, stairways, and upper stories, as well as many of the painted frescos. Moreover, the type of concrete he used is irreversible, making it impossible to correct as new evidence comes to light. These interventions are a major stumbling block to the 3,500-year-old site being inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Nevertheless, it’s widely regarded that Evans’ creative reconstructions have helped bring the ancient site back to life, helping visitors to make sense of its complex layout. And thanks to its popular association with the legendary Labyrinth, the Palace of Knossos is Greece’s second most visited tourist attraction after the Acropolis in Athens, drawing tens of thousands each year.

As for Minos Kalokairinos, the local Cretan who carried out the first soundings at Knossos more than 140 years ago, it’s hoped the exhibition at the Ashmolean will finally elevate him to the much-deserved status as the man who really discovered the “Palace of Minos.”